Last fall, a hangover remedy company called Blowfish produced a somewhat questionable map of the favorite beer brands in each state. According to the company’s data, collected by a third-party survey of more than 5,000 “drinkers” across the United States, the faux craft beer Blue Moon was proclaimed as the country’s most preferred brand. Considering Blue Moon’s relatively low market share, this company, which believes there’s actually a cure for hangovers, cannot be trusted for its methodological prowess.

“All kinds of opportunity for bias and bad decision here, and given the final goal (PR and marketing), I wouldn’t be all that confident about the results,” University of Kentucky geographer Matt Zook told Pacific Standard in an email, after being asked to take a look at Blowfish’s analysis. “Plus I’m a bit surprised by the Blue Moon response for multiple states, might be true but it seems to have a larger presence (particularly around Colorado with Coors) than I might expect. So I don’t think that this is all that meaningful or useful.”

Though the analysis does not come close to capturing the entire drinking population, especially the older boozers, the sheer sample size is impressive, and the mapping methodology is statistically significant.

Fortunately, Zook, a dedicated beer swiller, and his colleague Ate Poorthuis have stepped in to do a more careful analysis of which beers command the most intense interest in specific regions—at least when it comes to penetration on social media. Their maps appear as a chapter in a new book, The Geography of Beer, published by Springer. Zook and his research partner analyzed almost a million “geocoded beer tweets” produced between 2012 and 2013 that were drawn from a larger database known as DOLLY, a university project that houses billions of location-based tweets, to determine what beer brands get discussed on social media all across the United States.

Though the analysis does not come close to capturing the entire drinking population, especially the older boozers, the sheer sample size is impressive, and the mapping methodology is statistically significant. Additionally, voluntary tweets do not produce the response bias that participants might experience answering questions about beer brands on a formal survey.

THE ACADEMIC DISCIPLINE OF beer geography is shamefully diminutive, mostly represented by the other authors that appear in the newly released book. But Zook has been studying beer for a while, and geography for even longer. Right now, his preferred brewski “is probably West Sixth Amber, but some of that has to do with the fact that the microbrewery opened up a couple of blocks from my house,” he said in another email. “What’s not to like?”

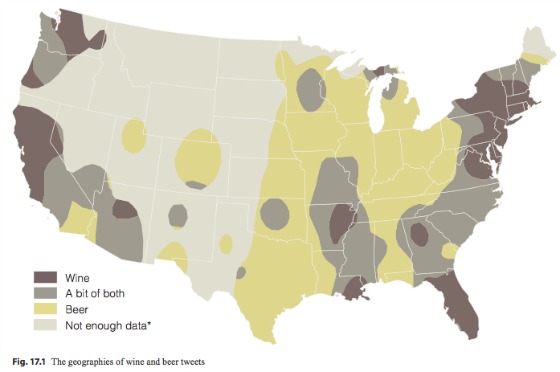

Though this project was focused on beer, the pair’s first map sought to locate the country’s most dedicated beer evangelizers by separating them from the winos. The researchers completed side-by-side beer and wine tweet-keyword searches of the raw data. Unsurprisingly, the results indicate that people closer to areas of wine production, such as Napa Valley in Northern California, Willamette Valley in Oregon, and upstate New York, tweeted more about boozy grape juice. “In short, the bicoastal regions of the United States are more partial to wine, or more specifically, have a greater intensity of wine tweets, than beer,” the authors write. While the Midwest, a sea of lager hue in the map below, is a barley pop heartland:

In contrast, much of the Midwest—stretching from Eastern Pennsylvania to Minnesota—and the West South Central region—including Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas—is much more likely to be the source of beer-related tweets. Parts of this region, particularly the upper Midwest states such as Wisconsin and Minnesota, were settled by European immigrants from Northern and Central Europe and have a strong cultural tradition of beer brewing and consumption.

Take a look:

Next on tap was an analysis of which areas the go-to cheap light beers dominated (“four out of the top five selling beers, as measured by sales, were light beers” in 2012). No Blue Moons here. As you might expect, the crisp Coors Light enjoyed patronage, or at least Twitter currency, in the Denver area and surrounding Rocky Mountains, close to its Golden, Colorado, headquarters. Super colds, as Coors Lights are termed by some, like the guy reppin’ his brand below, also dominated in areas of California, Washington, Oregon, and Arizona.

For the uninitiated, this video deserves a whole other case-study of its own:

Beyond super colds, the data (which did not filter for positive or negative ratings but just counted mentions) indicated that on the eastern side of the country and in the South, Bud Light was the talk of the party. “The most obvious pattern is that the two largest brands, Bud Light and Coors Light, dominate the light beer cyberscape of the United States which is hardly surprising since their combined sales dwarf the other two beers by a ratio of 2.5 to 1,” the geographers write.

Interestingly, the Midwest was mostly split between Busch Light (Bud is manufactured by the same conglomerate) and Miller Lite (a Coors brand). My own anthropological experience confirms the validity of these observations. In my collegiate days at Northwestern University, just outside Chicago, Illinois, I regularly purchased, poured, and beer-bonged Busch Light at tailgates. I miss you, Busch Light.

In a throwback to classic map-making jargon, the researchers also point out that data was not robust enough for many of the Western frontier states: “However, these areas are lightly populated, which equates strongly with low levels of tweeting activity, and therefore remain uncategorized in this map in a repetition of the classic ‘interior unknown’ labels of nineteenth century colonial maps.”

For the next undertaking, the geographers went beyond Light and looked at some of the popular heavier, but still cheap, stuff.

My only confusion with the heat maps below was what Yuengling—the country’s oldest operating brewery, which offers a classic Pennsylvania lager—was doing with activity in the godless state of Florida. Apparently, the company also runs a brewery in Tampa. Go figure.

Thankfully, the refined Dos Equis outperforms its ugly cousin Corona, an elixir with a faint taste of urine, in the Southwest. There is really nothing better than some Dos Equis-fueled saturnalia in a warm climate. And I can confirm, as these maps attest, that Goose Island is what you drink in the Midwest once you’ve graduated from chugging Busch Light.

The final map expands its brand searches to include some smaller names, and it clusters them spatially based on a percentage comparison to their aggregate mentions. “The result is more difficult to interpret but that is intentional as it demonstrates the complexity of beer cyberscapes, particularly in regions such as the Midwest and Northeast in which multiple and competing local beers were included,” the researchers write.

According to the researchers, the maps prove that “cyberscapes” closely align with the “historical and material presence of beer production and consumption.” As they conclude: “In short, this exercise in mapping georeferenced social media about beer shows how tightly imbricated the material and digital worlds are in the twenty-first century.”

Zook likes his microbrew back in Kentucky, sure. But I also asked him to choose a favorite brew from the cheaper varieties he analyzed. “In terms of the ones listed in the chapter it would be a toss up between Saranac (from grad school days in upstate New York) and Sam Adams (which I know back from the days of it being a funky little microbrewery in Jamaica Plain, MA),” he wrote in an email.

In conclusion, Corona is the worst.