Bill Gow is a true gentleman. The kind of old-fangled rancher who tips his cowboy hat to a young journalist as he declares, his voice carrying a subtle twang: “Pleasure to make your acquaintance, ma’am.” He’s tall and sturdy, with an air of calloused invincibility that comes from spending a lifetime working outdoors, raising cattle and carrying out the innumerable chores such a vocation entails.

On a bright and breezy summer afternoon, he gives me a grand tour of his 2,500-acre property in southern Oregon’s Douglas County. We drive past his two children’s homes, just minutes from his own; past the killdeer nest his granddaughter found just the day before my arrival on the edge of a gravel road that cuts across his land; past the arena he built on a hilltop for his wife, who he met in the ’80s when she was on the Oregon State rodeo team. When they first moved to this land in 1991, they were living off little more than spring water and deer meat. It’s not hard to see this land means a lot to Gow. It quite literally kept him alive.

Suddenly, Gow pulls off the road and peels across a sea of overgrown green and yellow grass. We come to a stop just short of a point where the meadow gives way to a steep slope. He walks up to the edge of the ridge, and Stacey McLaughlin, his neighbor, who has been tightly gripping the handle above the window in the back seat for much of the ride, gets out of the car and follows. For a moment, they quietly stare east across a rolling carpet of fir trees.

“I see you dressed up for this interview Bill,” says McLaughlin, eyes bright and cheeks whipped rosy by the wind. (Gow is outfitted in a faded blue flannel; one sleeve features a gaping tear at the elbow.) Though Gow and McLaughlin banter like siblings, the truth is that they couldn’t have less in common: She’s as short as Gow is tall, as liberal as he is conservative. The two would share almost nothing but a zip code if it weren’t for the Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline: a proposed 36-inch, underground pipe that might someday funnel natural gas across the state—and their backyards—to an export facility on the coast. Just about the only thing they agree on is that it should never be built.

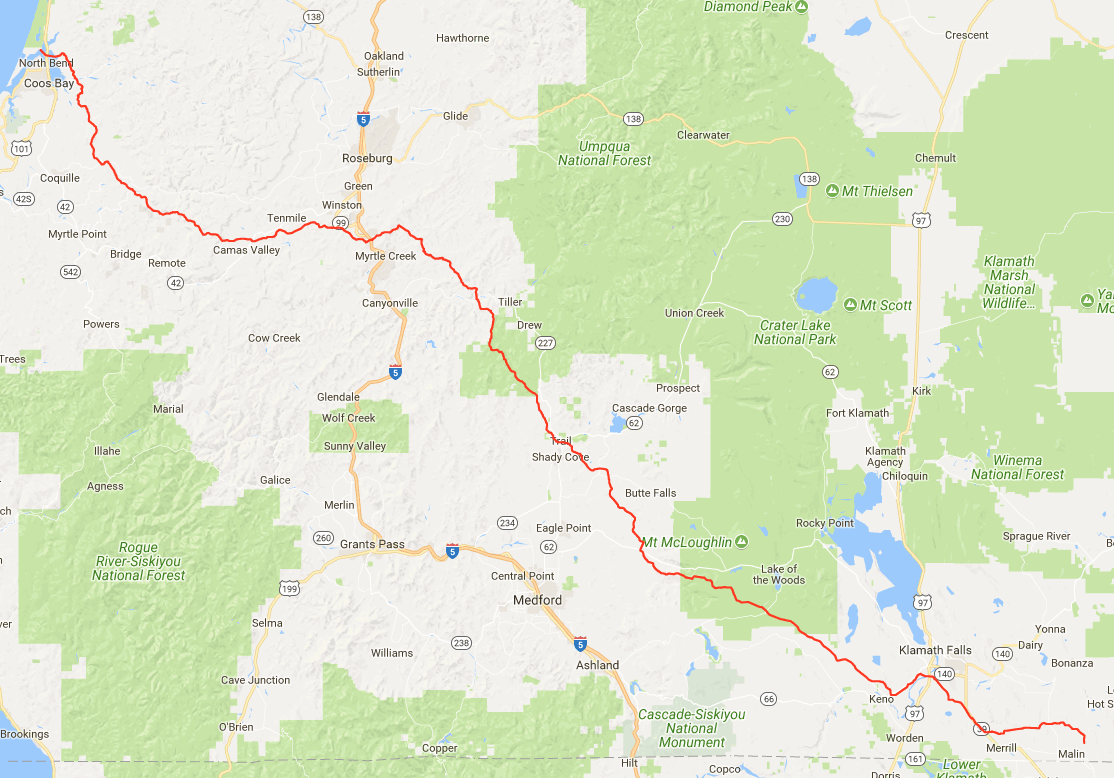

Gow and McLaughlin are two of more than 200 landowners whose property the Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline would directly cross. Many of them have been fighting the project for well over a decade. The plan calls for the pipeline to snake for 229 miles across southern Oregon, spanning all the way west from the tiny inland town of Malin, to an export facility named Jordan Cove LNG in the port of Coos Bay, a coastal city of about 16,000. From there, the natural gas would be compressed into a liquid and shipped to Asian markets. The export facility and pipeline, together called the Jordan Cove Energy Project (hereafter, Jordan Cove), exist only on paper for now. But its developers hope to be operational by 2024.

The energy company behind Jordan Cove has changed several times since the first public hearings on the project were held in 2005. After a series of acquisitions and reorganizations, a Calgary-based oil and gas company called Pembina officially took the reigns in 2017, which has the landowners more worried than ever.

“We know that Pembina has the resources to take this further than Veresen [the previous backer] ever could,” McLaughlin says. “They are upping the ante, they’re pushing and working really hard to pick off vulnerable landowners. There’s just such a predatory nature to all of it. We have a higher level of fear after this sale than we did before.”

Gow first heard about the pipeline in 2007, when he received a letter in the mail from the Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline, alerting him that the pipeline’s proposed path crossed his land.

The letter offered Gow a large sum of money to lay pipeline across 26 acres of his land. He refused to entertain the idea. “They’ve offered me $14,000 to come through two miles of my ranch,” Gow says. “I’ve spent more than that going to meetings for the last 10 years just to fight this thing.” He knows pipeline employees would have unmitigated access to his private land to monitor and maintain the pipeline once it’s in the ground, and he won’t be able to log, build, or even drive heavy equipment over those 26 acres. “Why should I have to give up my private property rights for some fly-by-night outfit to come through and take my land so they could make a profit?”

The first offer McLaughlin and her husband received in the mail came in 2011, for a couple thousand dollars, she recalls. They turned it down immediately. Eventually Pacific Connector came back with an offer topping $40,000, which they also rejected.

“The pipeline people think it’s about money,” she says. “They think all they have to do is come up with the right number. They aren’t understanding that there is no check to write me, there is no dollar amount to give me. It’s beyond them.”

From a higher point on Gow’s land you can spot McLaughlin’s home, sitting on the 357 acres she and her husband have owned for nearly 20 years. When she hikes into the pristine forest behind her house, she cherishes the feeling of walking through wilderness where no one has ever been before. Which made it all the more disturbing when flagged stakes began appearing on her property, marking the path the pipeline might someday take, and the towering oaks and unwieldy madrones in its way were casually spray-painted with an “X” for removal.

Since then McLaughlin has spearheaded the fight against the pipeline among the landowners—organizing her neighbors, attending meetings, and filing legal briefs with the Land Use Board of Appeals, the state agency that reviews all governmental land use decisions.

(Photo: Kate Wheeling)

Every time she files a motion, the law firm representing the pipeline files a motion to dismiss, citing case law. “I don’t know how to look up case law,” she says. “We have three lawsuits going at our local level. Once you move it into the courts, you have to know court procedure. We can never get past procedure to get to the merits of our arguments.”

From McLaughlin’s property the pipeline will head toward Juanita Saul’s 1.7 acres, where she’s lived for more than 60 years. It would pass within yards of her modest home, and could redirect the groundwater that she now relies on to fill her well. The pipeline will also cut diagonally across John Clarke’s 160 acres, where he built a family compound of three homes, made from timber harvested from his own land and nestled in a canyon. Clarke had no plans to abandon the place, but now he isn’t sure he can stay either: The pipeline will pass underneath the only road into and out of the canyon. When it reaches Deb Evans’ 157 acres, construction crews will clear cut 95 feet of her timberland on either side of the pipe’s path, and she would be permanently prohibited from growing trees—her livelihood—within 50 feet of the pipeline once it’s in place. They can’t just sell off their property either—at least not at market value.

“It’s already devalued our property,” Evans says, “and it doesn’t even exist yet.”

So far more than 90 landowners have taken deals offered by Pembina or its predecessors, while Gow and the rest are still holding out against the pipeline.

“What in the hell is a few thousand dollars in my life? To give up this? For money?” Gow says, looking out over the path the pipe will take as it approaches his ranch. “I ain’t going to do it.”

Of course, that won’t matter if the Department of Energy’s Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the agency that controls the United States’ natural gas industry, approves the Jordan Cove project. Pembina filed its applications for both the pipeline and the export terminal with FERC in September of 2017 (while the applications are separate, one cannot exist without the other). With FERC’s endorsement, Pembina can use eminent domain—a power that allows the government to seize private land for public use—to force the landowners to let the pipeline cross their property.

It’s the ethics of this political maneuver that are most troubling to Gow: “I really struggle with the fact that a foreign company can use eminent domain against American citizens to send our natural gas over to the Pacific Rim.”

Eventually, the pipeline will reach Oregon’s coast in Coos County—a cluster of salt-weathered port towns in the southwestern corner of the state. Jordan Cove plans to build the export facility in Coos Bay, the largest city in the county, on an overgrown stretch of sand spit that juts out into the Pacific Ocean.

From a parking lot on the sand spit, where a family has parked their RV and hauled up a cage full of crabs, Jody McCaffree points to the empty plot where the facility will sit—just left of the mountains of woodchips produced by Roseburg Forest Products awaiting export, and across the channel from the airport. McCaffree was born and raised in Coos County, and has become the leader of the local opposition to Jordan Cove since she went to a public meeting about the project back in 2005 “just out of curiosity.”

Back then, Jordan Cove was supposed to be an import facility, taking in gas from the Middle East and Russia for West Coast consumers. But by 2009, the oil and gas boom in the U.S. had begun; the amount of gas produced in the states increased from 2.1 billion cubic feet in 2008 to 15.2 billion cubic feet in 2015. The rise of fracking left the U.S. with a glut of domestic natural gas. As a result, prices fell and companies lost interest in importing the fuel. The focus then turned overseas.

In 2012, with increased demand for natural gas in markets abroad, Jordan Cove was reimagined as an export facility for cheap fracked gas from fields in the Canadian and U.S. Rockies. But by 2016, Jordan Cove still didn’t have any actual buyers lined up. FERC rejected the Jordan Cove Energy Project in March of that year—marking the first time in the agency’s history that it had denied a pipeline project—and again in December on appeal. FERC cited “little or no evidence of need” for the pipeline, given the lack of liquefied natural gas buyers, and “adverse effects on landowners.”

But the saga didn’t end there. FERC denied the project “without prejudice,” McCaffree explains, “[meaning] if they ever got contracts to sell the gas they could come back, and that’s exactly what they’ve done.”

According to Michael Hinrichs, the director of public affairs for the project, two Japanese companies, Itochi and JERA—the largest buyer of liquefied natural gas in the world—have committed to buying 50 percent of Jordan Cove’s capacity. “We’re advancing negotiations on a third customer and we’ve see increased interest from others, as of late, to see if there’s still capacity for them,” he says.

In December of 2016, even before the fossil-friendly Trump administration settled into the White House, the project’s operating company announced it would re-file for federal permits, with the hope that the new administration’s position on energy might encourage FERC to rule in its favor.

In April of 2017, Trump’s then-economic advisor, Gary Cohn, told a crowd at the Institute of International Finance, “The first thing we’re going to do is we’re going to permit an [liquefied natural gas] export facility in the Northwest.” Of course, the White House has no say over FERC’s decision. But two new commissioners have been nominated and confirmed to FERC since Trump took office; one of them, Robert Powelson, compared the actions of anti-pipeline activists to waging “jihad” against the agency.

(Map: Jordan Cove LNG)

But Jordan Cove still has to secure county- and state-level permits, as well as dredge permits and water quality permits and air quality permits. And McCaffree, who founded Citizens Against LNG, a group of Oregonians who oppose Jordan Cove through both protests and participation in the regulatory process, has a laundry list of reasons why those should not be issued: the threat to the local oyster industry; the proximity of the facility to the airport runway; the nearly 17,000 people living within the hazardous burn zone, all of whom would be at risk of suffering second- or third-degree burns if the facility’s tankers were to go up in flames; not to mention the fact that the facility will sit in a tsunami inundation zone in a region that’s long overdue for a megathrust earthquake. (The Cascadia fault line for now sits quietly just eight miles offshore from Coos Bay, but it’s expected to rupture within the lifetime of the facility, and it’s likely to produce a magnitude 9 or above earthquake.)

That last fact should be enough to prevent Jordan Cove from being built on the sand spit, according to McCaffree; Oregon’s statewide land use plan contains a provision prohibiting the construction of “hazardous facilities” in natural hazard areas. But, after some persuasion by the Jordan Cove lawyers, Coos County overruled the provision.

Oregon’s state officials, including Governor Kate Brown and Senator Ron Wyden (D) have tried to stay neutral. Senator Jeff Merkeley (D), who introduced the “Keep It in the Ground Act,” which would ban new fossil fuel leases on public lands and in federal waters, reluctantly came out against the project only last year, in a letter to the Medford Mail Tribune, arguing that the economic benefits don’t outweigh the climate impacts.

“Nobody wants to be the bad guy and say, ‘Jordan Cove, you can’t build this here,'” McCaffree says. “Somebody needs to have the balls—pardon my French—to say: ‘It’s not a good idea. You’re trying to do this on a sand spit in an earthquake subduction and tsunami inundation zone, at the end of an active airport runway, and you need to abandon it.'”

Another opposition group called Coos Commons, which overlaps with Citizens Against LNG in sentiment and membership but not in methods, also meets in the back corner of the Coos Bay library at least once a week. Coos Commons was behind a controversial ballot initiative—Measure 6-162—that aimed to undercut Jordan Cove by blocking the transportation of any fossil fuel within the county, as well as the development of any other “non-sustainable” energy system. In what would become the county’s most expensive election campaign to date, Jordan Cove gave over $600,000 to the Save Coos Jobs Committee—the group that campaigned against the measure. The Yes on Measure 6-162 group received just over $13,000 in donations. Ultimately the measure failed to pass. (Many voters, even those opposed to Jordan Cove, found the ballot measure confusing.)

“We cannot compete with Jordan Cove,” McCaffree says. “They kind of take over your town, they take over your elected folks, they come in and promise them all this money and it’s rather difficult for a local community, that’s rural like this, to overcome that.”

Environmentalists have their own concerns about both the facility and the pipeline. “The facility itself would become one of the largest climate polluters in the entire state,” says Hannah Sohl, the director of Rogue Climate, a local non-profit that advocates for clean energy. And while natural gas is often viewed as a cleaner alternative to coal or oil—gas emits about half as much carbon dioxide to produce the same amount of energy as coal—methane leaks occur all along its supply chain.

On the surface, the pipeline’s path as it currently stands will cross wetlands, old growth forest, and over 400 rivers and waterways—including the Rogue River, which drains from the Cascades across the state to the Pacific Ocean. The Rogue is one of the last intact spawning grounds for the chinook salmon, a threatened species in Oregon. On the private land bordering the river where the pipeline will tunnel underneath the Rogue, brightly colored anti-liquefied natural gas signs are posted all along the line of trees that follow the river bank.

Construction crews will have to drill some 80 feet below the river into the bedrock. But if anything goes wrong and that rock fractures, drilling fluid and mud could spew up into the water and pollute the river. The impacts could be even greater on small tributary streams. There, construction crews would clear away the vegetation around the stream, temporarily divert the water, lay the pipe down on top of the bedrock, and then cover it up. “You can’t put a 36-inch pipeline through a streambed [in a way] that’s not going to have extreme impacts on that waterway,” says Robyn Janssen, an activist with the environmental non-profit Rogue Riverkeeper.

Southern Oregon is unusual terrain for a pipeline. It has to cross a rugged, mountainous landscape and punch through the dense, volcanic igneous rocks that make up much of the region’s geology. “It would require a lot of blasting,” Janssen says, a process that is accompanied by considerable noise and air pollution.

To help offset these impacts, Jordan Cove has purchased roughly 100 acres of land in Coos County on the site of a defunct golf course, which will be restored to marsh and estuary habitats. “I’m all for creating a new sanctuary out of an old, crappy golf course, but that doesn’t mitigate the destruction,” Janssen says. “You can’t totally destroy a salmon-bearing stream in Klamath County and then fix that by planting a bunch of crap 100 miles away.”

Hinrichs, the Jordan Cove spokesman, says that the pipeline will not affect any salmon-bearing streams in Klamath County, and notes that a quarter of the 100 acres of habitat improvements are voluntary. “Perhaps most importantly,” he says, “all mitigation associated with our permits adheres to federal and state mitigation guidelines and is thoroughly reviewed by the appropriate agencies during the public permitting process.”

Of course, Jordan Cove is not without its supporters, including Coos Bay’s Mayor Joe Benetti, all three county commissioners, state Representative Caddy McKeown (D), and locals like Todd Goergen, for example, who owns an RV and ATV park on the sand spit.*

Goergen, a burly man with a boyish face and a quiet voice, sees Jordan Cove as a rare opportunity: a chance for the region to reverse its economic misfortunes. The unemployment rate, at 13.8 percent, is the lowest rate for the region in a quarter century, but remains more than three times the national average. Median household income in the county is just over $39,000—a full $20,000 below the national average. Without Jordan Cove, Coos Bay will “just become another little dying coastal town dependent on low-wage jobs and government transfer payments,” he says, sipping tea in a coffee shop that sits in downtown Coos Boy, on one of the sleepiest stretches of the iconic Highway 101.

In 1947, the Oregonian dubbed Coos Bay the “lumber capital of the world.” Back then, the timber industry employed nearly 90,000 people; up until the 1970s, wood products accounted for about 15 percent of the state’s gross domestic product (GDP). “In the heyday of Coos Bay it was the world’s largest port for the export of lumber and logs,” Goergen says.

Beginning in the late 20th century, stricter environmental laws, coupled with the recession and housing crisis of the 1980s, reduced timber harvests. Today, the timber industry employs just over 23,000 people, and wood products make up only 2 percent of the state’s GDP.

Construction of the pipeline and the export facility would create 6,000 jobs, according to Hinrichs, the Jordan Cove spokesman; he expects 30 percent of those jobs to be filled by people living within 50 miles or so of the facility or the pipeline. He says up to 80 percent of the jobs constructing the facility itself would go to Oregonians. Unsurprisingly, there is strong union support for Jordan Cove.

(Photo: Kate Wheeling)

The influx of workers to the region—the project includes a 2,100-person worker camp out on the sand spit—could bring upwards of $200 million to Coos County businesses, according to an economic analysis by Jordan Cove. Once in operation, the plant would provide around 150 permanent jobs, with an average salary of nearly $97,000 a year, not to mention billions in tax revenue for the state of Oregon over a 20-year period—the current projected lifetime of the facility. “When you break that down, it’s hundreds of millions of dollars to Coos County,” Hinrichs says.

Jordan Cove’s detractors argue that, even if the project does lead to an economic boom, a devastating bust will follow. “It would actually ruin the economy,” says Katy Eyman, an attorney and the current president of Citizens Against LNG. “It would be 6,000 workers coming in for a very short period of time, two to four years. That’s a 10 percent increase in the population of the area. A lot of businesses will build up to serve those people, they’ll earn a lot of money building these facilities, and then they will all leave and all the infrastructure that was developed to support them will be decimated by the loss of business.”

But Goergen sees Jordan Cove as a springboard: The revenue from Jordan Cove could help attract other industries by revitalizing Coos Bay’s port, which has seen the number of ship calls fall from over 400 a year at the height of the timber industry to less than 50 today. “It’s not going to return us to the old timber days but if you want a well-diversified economy this project can certainly help get us there,” Goergen says. “We can’t employ enough people flipping burgers and pumping tourists’ gas around here. I’m not knocking those jobs, but you can’t support a family on those minimum-wage jobs.”

Citizens Against LNG’s members meet after hours in the conference room of the North Bend Library, when the rest of the building is completely dark. The city of North Bend is a pocket of roughly five square miles of land almost entirely surrounded by the town of Coos Bay. Landowners from as far away as Jackson and Douglas counties show up to help plan protests, sign petitions, discuss updates, and settle on their next plan of action. They’ve tried to fight Jordan Cove within the legal process, appealing permits one at a time on environmental or zoning grounds. They’ve had several small victories—like blocking Jordan Cove from building its worker camp next to downtown North Bend and from building a turn lane on the transpacific parkway—but none that have derailed the project entirely.

Huddled around the table in the library conference room, the group workshopped a letter to FERC asking the agency to extend the public comment period on the project, and brainstorming ways to drum up public participation in a new round of scoping, where people affected by the project can raise environmental concerns to FERC staff. The scoping meetings were scheduled to begin again in just two weeks.

As the meeting stretched to the 90-minute mark, Gow shared an idea. “I thought it might be a good idea to somehow put signs along the edge of that burn zone that say, ‘Entering Jordan Cove Burn Zone,'” he said, much like the tsunami evacuation zone signs that are already posted throughout the seaside community. The group excitedly discussed how to pull off the campaign as they funneled out of the conference room. A few of the group members—Gow included—headed over to Seven Devils, a brewery around the corner, where the Coast Range Forest Watch was celebrating its successful efforts to block the sale of the Elliott State Forest to a timber company.

Private property rights may be Gow’s primary motivation for fighting Jordan Cove, but in the past few years he’s coming around on climate change. “I’m not as strong on this global warming thing,” he says. “My big thing is private property rights. I just don’t want the whole world to think it’s just a bunch of Earth babies that are fighting this thing.”

McCaffree, for her part, was not among those who went to Seven Devils after the meeting. The group was in the process of appealing one county-level permit Jordan Cove obtained for the export facility, and she had just two weeks to work on the legal brief. Eventually, in December of 2017, Oregon’s Land Use Board of Appeals would side in their favor—effectively revoking the facility’s land use permit.

But the project is hardly dead. “For a large-scale development project such as Jordan Cove, the requirement to remedy minor portions of the LUBA permit is common and not unexpected,” Jordan Cove’s president, Betsy Spomer, said in a press release. “We plan to fully address the items that require further action and expect to remain on schedule with our other permits and the current project timelines.”

“I’m just tired of fighting this thing,” McCaffree says.

*Update—April 15th, 2018: This post has been updated after it was called to our attention that we had mistakenly attributed Caddy McKeown’s position on Jordan Cove—one of support—to a different official who had, in fact, remained neutral on the subject. That official’s name has since been removed.