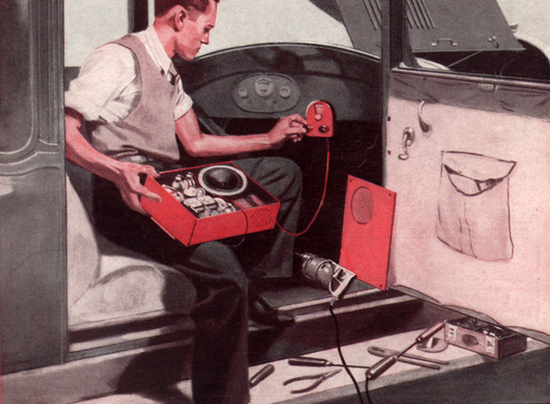

Illustration of a radio being installed in a car in the June 1933 issue of Radio-Craft magazine (Source: Novak Archive)

By some government estimates, 25 percent of motor vehicle accidents in the United States are a result of the driver being distracted. In response, state legislatures all across the country have passed laws to combat what many see as the main culprit—the now ubiquitous cellphone. With traffic fatalities on the rise, as the National Safety Council has just reported, driver distractions are back in the limelight.

Currently 10 states have laws banning all drivers from using handheld cellphones and 39 states ban texting while driving.

But the outcry over distracted driving is far from new. As radios were first being widely installed in automobiles during the early 1930s there were fierce fights over whether they should be allowed.

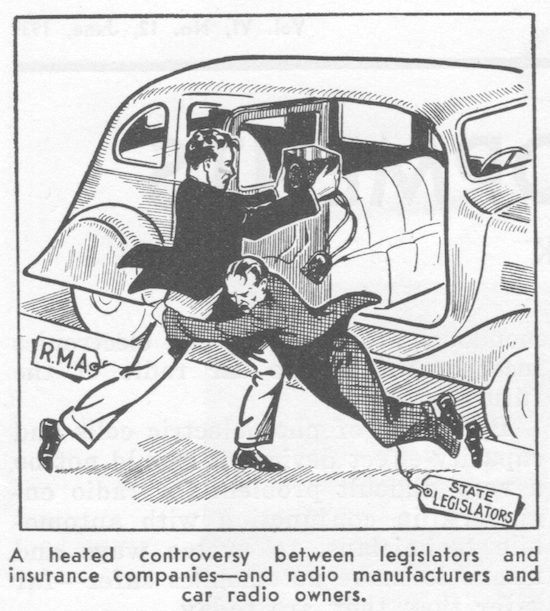

The June 1935 issue of Radio-Craft magazine explained the battle being waged between state legislators and radio manufacturers: “Ever since auto-radio installations became popular, a controversy has been going on—between legislative authorities and insurance companies on one hand, and radio manufacturers and car radio owners on the other—as to whether auto radio presented an accident hazard or not.”

In 1930 the former president of the Radio Manufacturers Association, C. C. Colby, claimed that talking to people in the back seat of the car posed a greater risk to public safety than the new car radio: “Radio is not distracting because it demands no attention from the driver and requires no answer, as does conversation between the driver and passengers. Motor car radio is tuned by ear without the driver taking his eyes off the road. It is less disconcerting than the rear view mirror.”

In the early 1930s legislators in states like Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Illinois and Ohio all proposed steep fines for drivers, while others imagined that making the installation a crime—since few automobiles came with them pre-installed—would help keep drivers safe. In May of 1935 state legislators in Connecticut introduced a bill that would have made the installation of radio into a car subject to a $50 fine, or about $825 adjusted for inflation. It didn’t pass.

The radio industry continued to insist that there was no evidence that radio contributed to accidents. Instead, they said, radio might actually reduce the number of collisions. Bond Geddes, executive vice president of the Radio Manufacturers Association, said in 1935: “Since that time [when auto radio first became popular] there has not been a single case according to any information in our possession where an automobile radio has been the cause of any major accident. Against this is the almost unanimous opinion of operators of automobiles equipped with radio that they tend to reduce speed and, therefore, are not a source of danger but actually become a safety factor.”

The battle continued for some years, but it wasn’t until the late 1930s that researchers really tried to study the effect car radios were having on accident rates. The Princeton Radio Research Project was started in 1937 and aimed to look at the effect of mass media (such as radio) on society. Edward A. Suchman took on the question of radio’s influence on car crashes in a paper for the project, which appeared in the Journal of Applied Psychology; his small study found no link between car radios and traffic accidents.

The problem with anti-cellphone laws is often one of enforcement. Who hasn’t bent the rules when we felt we could get away with a quick text behind the wheel? The takeaway from Suchman’s 1939 study was similar; different laws were passed all around the country to try to restrict radios in cars, but they were rarely, if ever, enforced.

Illustration from the June 1935 issue of Radio-Craft magazine (Source: Novak Archive)

As we move into the future, the number (and increasing size) of screens in cars will likely see new battles over distracted driving.

Tesla’s new Model S electric car also has its own screen, which some people have already objected to. After test driving the Model S, The Verge‘s Chris Ziegler was stunned that the web browser wouldn’t automatically disable when the car was in motion. Ziegler writes:

I was actually surprised that existing US or European regulations don’t prevent something like a giant touchscreen with a full web browser in a dashboard from being sold in the first place, but I think the Model S is a case where private industry has simply run circles around the molasses-esque bureaucracy of our government: in three, five, or ten years, I would be shocked if this kind of hardware and software configuration was legal. I don’t want a web browser in my car, and more importantly, I don’t want the drivers around me to have one.

By the end of the 1930s, about 30 percent of cars on American roads had radios. We’re still quite a ways from having that kind of large touchscreen penetration on today’s roads, but as Ziegler notes, it’s certainly the fight of tomorrow.