The vast majority of Americans—over 80 percent—oppose the idea of slaughtering horses in the United States. Not surprisingly, there was minimal public opposition when, in 2007, Congress, citing rampant welfare abuse and safety violations, cut off funding for the USDA inspection of U.S. horse slaughterhouses. This decision effectively ended the business of slaughtering horses domestically.

In November 2011, however, an agriculture appropriations bill signed by Congress reinstated funding for inspection. The legislative path for states to reopen horse slaughterhouses is now clear. Today, with the domestic cattle market in a drought-induced tailspin, New Mexico, Missouri, Wyoming, Tennessee, Iowa, and Oklahoma are on the verge of sending horses it once sent to Canadian and Mexican slaughterhouses into the clutches of domestic abattoirs. Other states, seeking a way to capitalize on horses that have lost their value or can be bought cheaply at meat prices, are eager to follow. A New Mexico meat processing plant has even made arrangements with the Navajo Nation to corral wild horses in anticipation of the impending slaughter fest. All that’s holding this off for right now is a lawsuit from the Humane Society of the United States.

They’re bucking horses that won’t buck and racehorses that won’t win and quarter horses that nobody is buying from breeders because hay prices are too high.

The pivotal piece of evidence that convinced Congress to change its mind on the matter of domestic horse slaughter was a GAO analysis published in June 2011 (PDF). Senators Herb Kohl (D-Wisconsin) and Roy Blunt (R-Missouri) and Representative Jack Kingston (R-Georgia) commissioned it. Titled, “Actions Needed to Address Unintended Consequences From Cessation of Domestic Slaughter,” the report found “a rise in investigations for horse neglect and more abandoned horses since 2007”—the year the plants were closed. The “unintended consequence” of closing horse slaughterhouses, the report explained, was an increase in the abuse of horses. Reinstating domestic slaughterhouses, it suggested, would diminish this rising problem of neglect among owners who neither wanted to keep their horses nor were willing to send them abroad for slaughter. This argument was one that the slaughter lobby has been making since slaughterhouse closings in 2007. Pro-slaughter advocates were more than pleased to hear the news.

Something about this report, however, seemed suspicious before it was even published. Charlie Stenholm, former Texas Congressman and now policy advisor to the D.C.-based law firm Olsson, Frank, and Weeda (which specializes in helping agribusiness negotiate federal red tape and recently hired an attorney who specializes in agricultural deals with Native Americans), told a conference of pro-slaughter interests in Las Vegas that the GAO report—which would not come out for another six months—contained very good news.

When the report officially dropped in June 2011, Stenholm was proven correct. The Senate quickly wrote an appropriations bill removing the provision that defunded inspection. Because the House had an amendment preserving the language, the bill went to committee, where the vote was three to one in favor of restoring funding for domestic horse slaughterhouses. Those three votes came, alas, from Senators Kohl and Blunt and Representative Kingston.

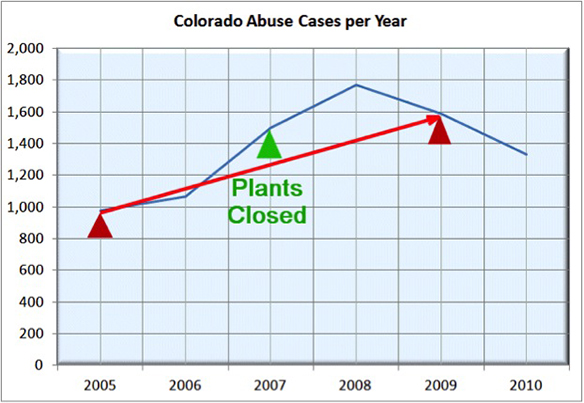

All very fishy. But what really stinks about the GAO report is the math. Because national data is not available on reported horse abuse, the GAO went to six states and found—in the only case of hard numbers that it provides in the entire report—that “Colorado data showed that investigations for horse neglect and abuse increased more than 60 percent from 975 in 2005 to 1,588 in 2009.” Sounds pretty dramatic—until you recall that the slaughter ban passed in 2007. Not 2005.

As it turns out, horse abuse in Colorado did rise rapidly from 2005 through the end of 2007 (before the ban). But, starting in 2008, it declined precipitously through 2010 (a year for which numbers are available but the GAO tellingly admitted). The report thus made it seem as if abuse spiked after the closing of slaughterhouses. In fact, it continued for less than a year after the ban was instated and then declined rapidly.

Figure 1: Colorado Department of Agriculture data

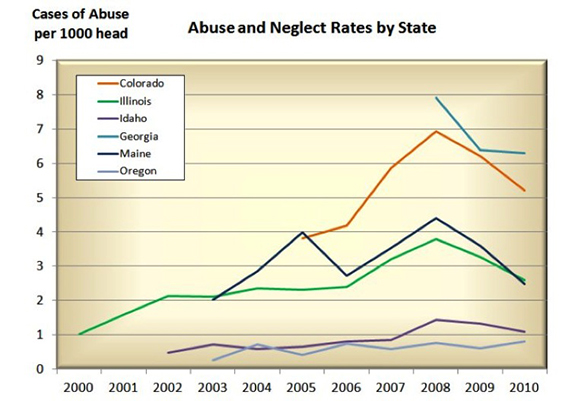

It is further worth noting that the GAO had access to similar figures on horse abuse investigations from five other states—Illinois, Idaho, Georgia, Maine, and Oregon. The GAO’s decision not to include this information makes little sense unless it was deliberately trying to skew the picture of horse abuse in favor of pro-slaughter interests. To wit: Four states for which there are data show a dramatic decline in horse abuse after 2007 while one—Idaho—shows no movement one way or the other. Ignoring these figures, the GAO decided instead to focus on Colorado, evidently hoping nobody would notice its creative presentation of the numbers.

Figure 2: Data from the agriculture departments of six states

Despite the report’s suggestion that the need for local slaughterhouses is an urgent matter, the GAO fails to note something quite extraordinary about the situation: Only about one percent of existing domestic horses are slaughtered every year. Ninety-two percent of that one percent, according to Temple Grandin, are healthy and devoid of behavioral problems. They’re bucking horses that won’t buck and racehorses that won’t win and quarter horses that nobody is buying from breeders because hay prices are too high. The only thing that’s urgent in this entire scenario is the desire to profit from sending these healthy horses to slaughter.

Horse abuse and neglect is a small problem that got smaller with the closure of slaughterhouses. The GAO—and the slaughter lobby it seems to represent—falsely presents it as a large problem getting larger. It wants us to envision a situation in which a recession and drought are overwhelming horse owners to the point that they’re neglecting sick and ailing horses en masse. Give them easy access to a domestic slaughterhouse, so goes the argument, and abuse will decline.

In fact, it is the exact opposite that’s true. Abuse went down after slaughterhouses were closed. All that domestic slaughterhouses would provide is an easy and profitable excuse to send many more healthy horses to a premature death for meat that we don’t even eat in this country. It’s all very sad logic upon which to rebuild an industry.