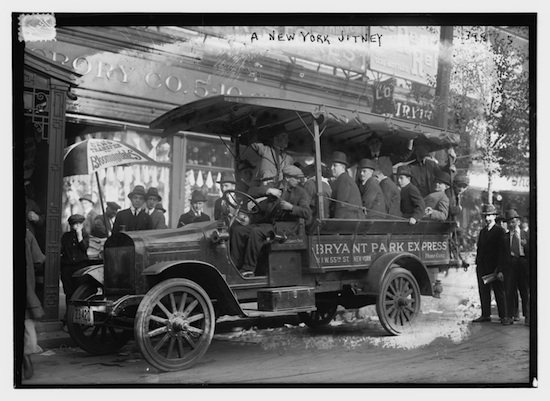

A “jitney” in New York, circa 1915 (Library of Congress)

There’s nothing hotter in Silicon Valley right now than “disrupting” the taxi industry. Of course, people in the tech world can’t get enough of the buzzword disrupt, but in this case the aggressiveness of the word actually seems to fit. Services like Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar are all disrupting the taxi industry with smartphone apps that allow you to hail and pay for rides from taxicabs, limos and sometimes even just regular people looking to “ride-share.”

Virtually every major city in the country is trying to shut down Uber, with taxi regulators up in arms over their brazen disregard for well-established taxi regulations—everything from rules about how fares are calculated to what kind of car can operate for various kinds of trips. This past August the California Public Utilities Commission issued cease-and-desist letters to the unlicensed ride-sharing apps Lyft and Sidecar. The companies vowed to continue service, despite the letters. It now looks like the commission is interested in re-evaluating these services and seeing how they might be able to operate in California lawfully.

But this isn’t the first time that we’ve seen a massive disruption in the taxi industry.

The 1910s saw the rise of the automobile, and along with it, the rise of the ride-sharing and alternative taxi service. Many of them unlicensed, they were known as a “jitney,” costing just a nickel, or about $1.10 adjusted for inflation. (At the time, the word “jitney” was slang for a nickel.)

The first known jitney in the U.S. started in Los Angeles in 1914. Thanks to the mild climate of Southern California, which allowed for the rapid expansion of open-air automobiles in general, there were an estimated 700 jitney vehicles on Los Angeles streets within a year. As Scott L. Bottles notes in his book Los Angeles and the Automobile, “By late 1914, some enterprising motorists had established the nation’s first jitney companies, using oversized automobiles to ply the streets in search of customers. The automobile jitney offered flexibility, convenience, and speed to those disappointed with streetcars.”

Jitneys were seen as direct competition for the nation’s streetcar services, many of which were angering riders over their unwillingness to improve their overcrowded and increasingly undependable services at a time of recession. By 1915 the jitney vehicles were carrying about 150,000 Angelenos per day and the jitney had swept the nation, operating in more than 40 U.S. cities including San Francisco, Seattle, Denver, New York, and Portland, Maine.

The city of Los Angeles wasn’t so much interested in regulating the jitney buses as they were figuring out how to direct people back to using the railways. Shortly before Christmas of 1914, Mayor Henry Rose of Los Angeles sent a message to the L.A. City Council laying out the amount of money that the railways (and thus the city) were losing by people using the services of jitney vehicles:

Assuming that the 700-odd auto buses operating in Los Angeles are averaging $3.00 a day in fares, we have a total of $2,100 or about $60,000 a month, subtracted from the earnings of the street railways. How does this affect the public? As is well known, the street railroads operate under franchises which entail heavy expense for street maintenance, taxes, and public improvements. It is estimated that the street railways maintain at least one-third of the streets along which their tracks run, at a cost to them of upward of $350,000 a year.

The jitney became so popular so quickly that a paper was already published in the July 1915 issue of the Journal of Political Economy titled, “The Economics of Jitney Bus Operation.” The paper speculates as to why the jitney had exploded in popularity in such a short period of time. The economic recession of 1914 contributed to many men being out of work. These men who would normally be working in factories or other service occupations were taking to the streets attempting to start their own businesses. Another reason for the explosion of the jitney is the emergence of a new secondhand market: the used car. The used car (and rapidly declining prices of new cars thanks to the Model-T) meant that the there was relatively low overhead in the jitney business and at least for the time being, virtually no regulation.

The Journal of Political Economy even notes more minor but important advantages that drove the people of the 1910s to the jitney service, like the recent restriction of smoking on many railcars: “The smoking privilege has very largely been curtailed on electric railway cars because only a minority of the passengers would be favored by its retention.” The open-air jitney didn’t keep anyone from lighting up.

Regulation eventually caught up with jitneys. The city of Los Angeles clamped down on these unregulated taxis (after much protestation by the streetcar companies) and by 1918 the jitney was pretty much extinct in the city and heavily cut back by as much as 90 percent across the U.S.

It remains to be seen how long services like Uber will continue to exist as long as they continue to disrupt the established taxi industries. But if history is any guide, you can’t fight City Hall. In the meantime, anyone for slugging?