On Monday, in the largest reduction of federal land protections in United States history, President Donald Trump signed proclamations slashing the area of two national monuments in Utah. That same day, with just minutes to spare before midnight on the East Coast, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition—a first-of-its-kind alliance between the Hopi, Ute Mountain Ute, Ute Indian, Zuni, and Navajo Nation tribes—filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration, claiming that the president’s actions violated the Antiquities Act. “[The tribes] wanted to file it the same day to show that they were fearless and ready to go,” says Natalie Landreth, a senior staff attorney for the Native American Rights Fund who represents the Hopi, Ute Mountain, and Zuni tribes.

Both the Trump administration and the Utah congressional delegation have tried to frame the contraction of the monuments as a restoration of states’ and individuals’ rights. Trump has repeatedly claimed that his Democratic predecessors overstepped their authority, as its laid out in the Antiquities Act, in the designation of Utah’s national monuments. In April, he ordered Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke to review 27 national monuments created since 1996 (the year President Bill Clinton designated Grand Staircase-Escalante a national monument). Among those monuments is Bears Ears, nearly 1.4 million acres set aside by President Barack Obama in the final weeks of his presidency. In Salt Lake City on Monday, Trump said he had “come to Utah to take a very historic action to reverse federal overreach and restore the rights of this land to your citizens.”

“Public lands will once again be for public use,” Trump said on Monday, rehashing the myth that the national monument status limited individuals access to the land. When the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition was campaigning in 2016 for national protected status for what would become the Bears Ears National Monument, Senator Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) suggested tribes didn’t know what was good for them. “The Indians, they don’t fully understand that a lot of the things that they currently take for granted on those lands, they won’t be able to do if it’s made clearly into a monument or a wilderness,” Hatch told the Salt Lake City Tribune. When asked for specific examples, he added: “That’d take too much time. Just take my word for it.”

But Obama’s presidential proclamation that created the Bears Ears monument only prohibited three things, according to Landreth: looting, off-trail ATV use, and mining and gas exploration. “The Obama administration put in a paragraph that specifically preserved hunting and fishing rights for people, grazing leases, gathering rights, rights to even take firewood for ceremonial uses,” she says. “When I was listening to them talk about it yesterday, it felt like, wait a minute, did they actually read the proclamation or are they deliberately being untruthful?”

The decision, which would cut Bears Ears National Monument by 85 percent and Grand Staircase-Escalante by 50 percent, is just the latest milestone in the president’s quest to roll back both regulations on his predecessors’ legacies and to reward the fossil fuel industry—which donated over $1.1 million to his campaign.

Many of the local lawmakers who celebrated Trump’s decision have deep ties to the fossil fuel industry. Senator Mike Lee (R-Utah) has received at least $253,415 in donations from the oil, gas, and coal industries in the last three election cycles, while Hatch received at least $471,250, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. And industry interest in the land is no secret: In the last five years, the energy industry has tried and failed to lease over 100,000 acres of land within or near the Bears Ears monument for oil and gas development, while mining companies covet the vast coal deposits beneath Grand Staircase-Escalante.

The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition is arguing that it’s actually Trump who overstepped the boundaries of his authority. The Antiquities Act gives presidents the power to create national monuments, but, according to the complaint, the power to revoke or reduce those monuments lies exclusively with Congress.

The outcome of the case could affect the future of all 129 national monuments across the U.S.; if the White House can declare that the land cut from Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante is “not of significant scientific or historic interest” to warrant protection (as was the case with its most recent proclamations), then the Trump administration can do the same for any national monument. But this issue is about more than just environmental protections and conservation; it’s about tribal sovereignty.

Bears Ears was “the first truly Native American monument,” Landreth says; it was the tribes that set its boundaries and pushed for its creation. It’s telling that, while all national monuments are under threat, Bears Ears was one of the first to be struck down. For Landreth’s clients, it’s not just land that they stand to lose, but their cultural heritage, their beliefs, and their link to their ancestral homeland. Here is what’s at stake in Utah.

A Rich Record of Human Heritage

An archeological record of the earliest human civilizations on this land, like the Clovis people, who lived within the Bears Ears region 13,000 years ago when now-extinct mega-fauna like mammoths and ground sloths still roamed the land. Bears Ears contains approximately 100,000 archeologically significant sites, including dwellings, graveyards, shrines, ceremonial sites, and a record of rock art dating back at least 5,000 years—which makes the region a hotspot for looting.

When cultural resources like these are pillaged, it threatens the modern-day tribe’s connections to its heritage and ancestors. “The modern day federal lands of the Bears Ears region are the Hopi Tribe’s ancestral lands,” Herman Honanie and Alfred Lomahquahu, the chairman and vice chairman of the Hopi tribe, respectively, which claims the Puebloan groups that first settled the region as their own ancestors, wrote in a letter to Obama in November of 2016. “We have long requested avoidance and preservation of our ancestors’ remains, but the federal land managers of the Bears Ears region simply lack the capacity to do so…. Without a national monument designation, these desecrations are only sure to grow in the years ahead.”

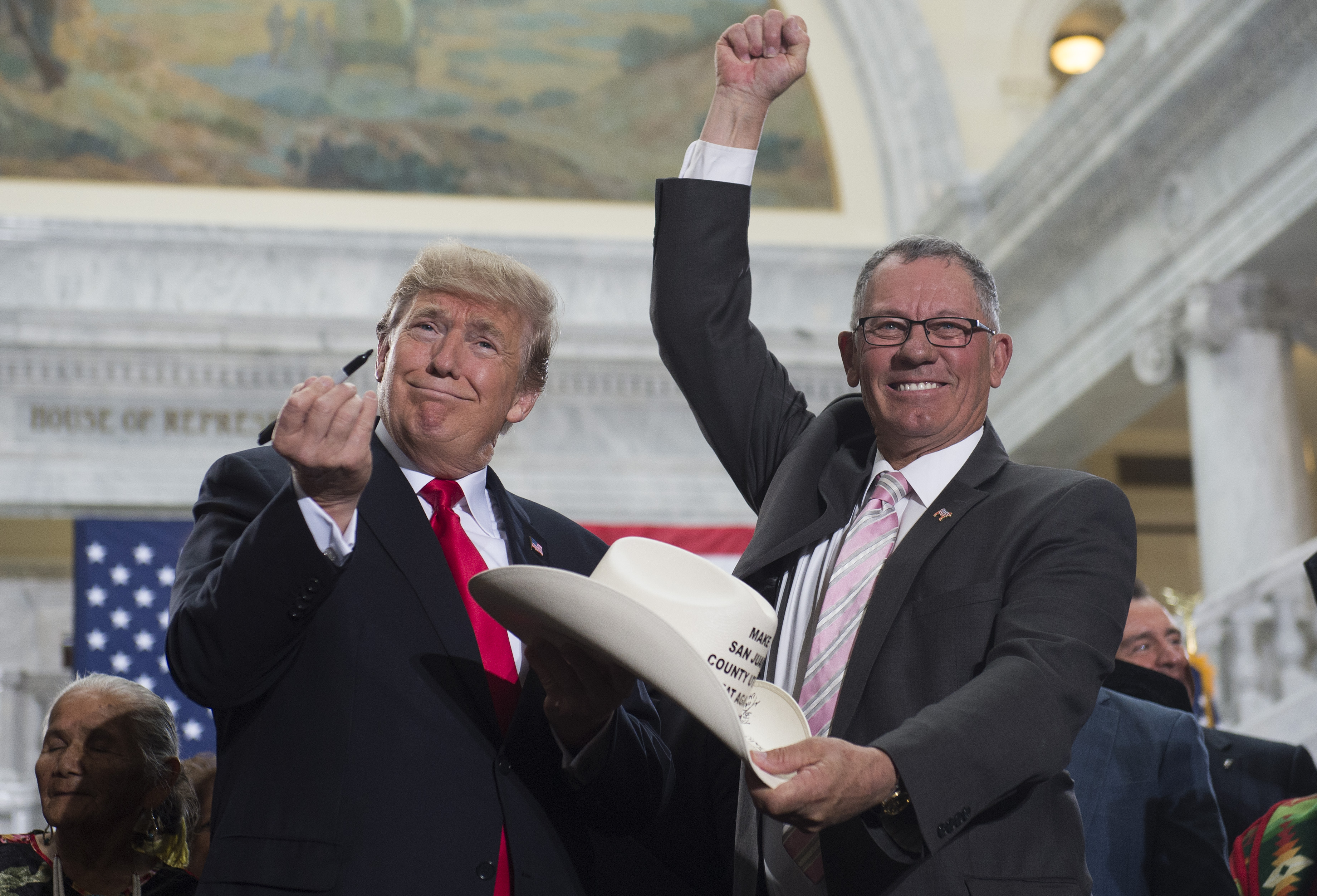

(Photo: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images)

A Modern Way of Life

It’s not just about protecting the landscape’s Native American relics; today, tribes still rely on the land much the same way their ancestors did in the past. “Tribes in the region continue to use the Bears Ears region to collect plants, minerals, objects, and water for religious and cultural ceremonies and medicinal purposes,” according to the Native American Rights Fund. “Native people hunt, fish, and gather within Bears Ears, and they provide offerings and conduct ceremonies on the land. In fact, Bears Ears is so culturally and spiritually significant that some ceremonies use items that can only be harvested from Bears Ears.”

The Right to Clean Air and Water

Beyond the threat to cultural resources, the Ute Tribe is familiar with the negative health effects that all too often accompany development of extractive industries. “As the residents of the nearest community to the nation’s last remaining conventional uranium mill at white Mesa, Utah, our people continue to suffer under the toxic legacy of uranium mining, milling, and uranium waste processing,” Harold Cuthair, the chairman of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, wrote in a 2016 letter urging Obama to designate Bears Ears as a national monument to put a stop to any current and future mining. “Paramount to the Tribe is our concern for the future of, and our rights to, our water, air, lands and the continuing effects of the mill on our people.”

A 25-Million-Year Fossil Record

Researchers refer to Grand Staircase-Escalante as the “science monument” and a “living laboratory,” where scientists can probe ecosystems both past and present for insights. “The Kaiparowits is one of the last untapped dinosaur graveyards in the world,” Alan Titus, a paleontologist for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, told High Country News. Beneath the monument’s Kaiparowits plateau—a dry, flat expanse that was once a lush swampland next to an inland sea—layers of fossils laid down over millennia are surrounded by billions of tons of coal. But opening up the region to mining development would threaten not just one of the best-preserved fossil records in existence, but the unique insights into evolution, deep time, mass extinctions, and climate change that such a record might provide.