In an innocuous meeting room on the south side of Newark, a small city in central Ohio, about 20 people, members of the Newark Think Tank on Poverty‘s leadership team, are gathered on a Sunday afternoon in late October. They are deciding on a new campaign, and Eric Lee is hoping it will focus on addiction—hoping that, as an organization, it will begin to advocate for equal treatment for all users, whether their drug of choice is opioids or methamphetamine.

The think tank, focused primarily on poverty, re-entry, and housing, is now applying its grassroots organizing model to the addiction crisis here in central Ohio, what many consider to be the heart of a nationwide epidemic. Allen Schwartz, a community organizer and one of the group’s founders, is running the meeting, a wide-ranging discussion focused on Newark’s problem with meth, which he says is viewed mostly as a “poor man’s” drug. Only half of the crisis is being addressed in this community, he says. Unlike opioids, which dominate the headlines and produce the spectacle of an overdose, meth kills slowly—people, and families, and communities.

There’s a lot of skepticism here. Some wonder if state and federal grant money is earmarked exclusively for opioids or if it can be used for meth. Some wonder if there’s going to be enough money at all. And some wonder if the people who need resources will actually have access to them.

Eric sits directly across from Schwartz. He’s quiet, contemplative, a little uneasy. Eric’s strength is “the one-on-one” and the outreach; he’s not into deliberative processes. But he was central to the think tank’s first major campaign, to “ban the box,” meaning eliminating questions about felony convictions on employment applications in Newark and across Ohio. He lobbied in Columbus and knocked on doors. He knew the ban would be a step toward better support for people getting out of prison. Since that campaign, the think tank has successfully placed its members on the boards of a number of groups throughout Licking County, where Newark is located, but it’s struggled to recapture the energy that the ban-the-box movement generated.

Now there’s an issue for it to address, one that many members have direct experience with, a collective something from which they can draw energy: how hard it is to stay sober if you’re poor. They feel that the subject of meth use is being overshadowed by opioids because there’s no medically assisted treatment for the former. And they’re concerned that meth users aren’t treated the same—in part because their demographics trend poorer and less educated.

After about half an hour, Eric finally speaks up.

(Photo: Will Widmer)

“The only thing that I wanted to say was, you’re leaving out taking this message to the street just like with ban the box. … We went out, we got people it affected directly, and we had them tell our stories,” he says, explaining that he’s seeing a lot of meth use in the community, affirming what everyone here knows.

“The last thing I’d want to see,” Eric says, “is us making all these plans, and we leave the addicts out—we leave the stories out.”

The United States is in the middle of an unprecedented public-health crisis. In both 2016 and 2017, more Americans died from drug overdoses than died in the Vietnam War or in the worst year of the AIDS epidemic. And the national story about Ohio, the one that has gotten a lot of press since the election of President Donald Trump, is that the state is ground zero for this crisis. Since 2000 the accidental overdose rate in Ohio has increased six-fold; today, overdose is the leading cause of death for Ohioans under the age of 55.

Licking County is, in some ways, just another victim. In this county of about 170,000 people, there were 18 overdose deaths in 2016; in 2017, there were 41, the majority involving some form of opioid. The crisis has had a wide reach. In the summer of 2017, the wife of state representative Scott Ryan was charged with two felony counts for stealing opioid painkillers. Ryan lives in Newark and has been a vocal supporter of measures that could help address what’s happening. Even the well-off and well-respected are not immune.

And yet it’s not as bad as in many other places. The age-adjusted death rate per 100,000 people, from 2011 through 2016, was 13 in Licking, versus 42.5 in Montgomery County, home of Dayton, for example. In this regard, Licking County is below average.

Save for Newark, most of the county is rural, even though it’s in the orbit of the Columbus metropolitan area. Unemployment is low, home and automobile sales are up this year, and there’s an energy in the community as it shakes off the Rust Belt moniker. The county is attracting employers like Amazon and Facebook on its western edge. And Newark’s historic downtown square is getting a facelift, including a gorgeous, new, outdoor market space, hip restaurants, a cutting-edge music venue, and the preservation of a Louis Sullivan-designed building.

But the long-term effect of this epidemic, crisis, catastrophe—call it what you will—will be a strain on the economy and on social services, especially the county’s foster care system. The numbers are staggering. At the beginning of 2017, there were 366 children in foster care; as of March of 2018, there were 530—86 percent of new entrants coming from homes where there is addiction. This means a generation of young people with dislocated childhoods. It also means overburdened social workers, counselors, law enforcement officers, emergency caregivers, and educators.

There are interventions for addressing addiction, of course, but not nearly enough. Researchers with The Ohio State University’s Swank Program in Rural-Urban Policy note that, “in the best-case scenario, Ohio likely only has the capacity to treat 20 percent to 40 percent of [the] population abusing or dependent on opioids.”

(Photo: Will Widmer)

In Licking County, there aren’t enough beds for detox, not enough spots for inpatient or intensive outpatient treatment, not enough sober-living facilities, not enough medically assisted treatment options. If you have private insurance or Medicaid, there are a few additional options outside the county, but only if there are beds available. Sometimes those beds are a long car ride away.

And though it might seem this way as viewed from the outside, opioids are not the only street drug in town. Meth use appears to be on the rise. A National Forensic Laboratory Information System query of the Columbus region from June of 2016 to January of 2017 counted 464 meth cases for this period, with almost half of those from drugs seized in Licking County.

Lieutenant Paul Cortright, commander of the Central Ohio Drug Enforcement Task Force, says meth is still available in powder form, but most of it is crystal—the stuff made by cartels in so-called superlabs, not by locals in their kitchens. There’s so much coming up from Mexico, and it’s so cheap, he says, that it’s almost unnecessary to manufacture it here. Over the summer, three men, allegedly tied to the Sinaloa Cartel, were arrested after a traffic stop. A search of their hotel room uncovered $15,000 and 12 pounds of meth—enough for nearly 30,000 lethal doses.

Cortright, who has been working on narcotics for 28 years, says this is as bad as he’s seen it.

“I would say that it’s worse because we’re dealing with drugs that will kill you more quickly than drugs did back when I had a mullet,” he says. “In the ’80s there was cocaine and crack houses, but people weren’t dropping dead.”

Eric Lee rolls his eyes. He’s heard this talk about rehabs before—this one’s the best: it’s going to save him if he can just get there. Now he’s hearing it from Johnathon Chaney, another user he’s trying to save, another user he’s not trusting.

Johnathon sits on the edge of the bed at the Budget Inn in Newark, flipping a cigarette in his hands. Eric stands by the door, hand resting on a wood-paneled table. He’s been in the room for almost an hour and he’s yet to sit down as Johnathon tells his story.

A decade earlier Johnathon was making good money, had savings, owned his home. But after a workplace injury, a doctor prescribed opioids. Now he’s here, at the crossroads of recovery and overdose. And, he says, he doesn’t want to go through the withdrawal anymore.

“You want it as soon as your eyeballs open,” Johnathon says. “As soon as your brain starts running, your main concern is getting well. That’s what they call it, ‘getting well,’ because you’re in withdrawal. You’re physically sick. Your body hurts. Your muscles contract. You puke and you shit.”

Eric listens with the patience of a man who has heard it all before—of a man who spent 20 years in and out of prison, in and out of rehab himself, and who is now clean going on 15 years. When not taking classes to become an addiction counselor, Eric mentors others like him. On Tuesday nights, he leads a support group for people on judicial release and, on Wednesday nights, a recovery group. In his free time, he sponsors, formally and informally, dozens.

He finds them, or they find him—smoking cigarettes after recovery meetings, eating lunch at the Salvation Army, or hanging out at the Main Place, a mental-health day program. Because of this, Eric has an important vantage point for understanding the addiction crisis. He sees it from above and from within, and no one is paying him to do it.

Today, Johnathon thinks he’s won the lottery—a spot in The Refuge, one of the best programs in the state, he says. A week from today, a guy named Steve is going to drive him the two hours down to Vinton County and check him in.

(Photos: Will Widmer)

(Photo: Will Widmer)

But between this moment and that, he must stay clean and sober; the rehab doesn’t offer detox. This means he must avoid the temptations just outside the door of his motel room, the trap houses down the street, the users who crash here. Before getting a room at the Budget Inn, Johnathon slept in a dirty old recliner, wedged between two buildings, covering himself with a faded, blue moving blanket. Now the St. Vincent de Paul charity is covering the $50 a night to keep a roof over his head until he gets to rehab.

“None of that shit matters,” Eric says, “if you don’t want to do it.”

Eric isn’t sure Johnathon can make it if he doesn’t recognize the precariousness of his situation, if he doesn’t make the choice, if he doesn’t find a supportive community right where he is.

“Well, everyone says it’s a good program,” Johnathon says, his voice rising in frustration before he stands up, brushes past Eric, and walks to the door, cigarette in hand. He cracks open the door, lights the cigarette, and drags deep.

Johnathon is a slender, boyish 40-year-old with a close-shaved head and a little stubble. His eyes grow big for emphasis and shut tight when his dimples emerge. He looks tired. A blue ball cap hides his eyes as he gazes across a wet parking lot. It’s a gloomy day in Newark, and Johnathon’s mood fits nicely.

Eric is burly with a receding hairline and a two-inch ‘fro. He takes Johnathon’s pouting in stride, knows it’s part of the process. Eric would like to find work as an addiction counselor, though he’s a de facto one already—officially as a sponsor and unofficially as someone making up for the mistakes of his past by helping others avoid them.

Johnathon comes back inside and sits back down just as Eric turns to leave.

“I’ll be checking on you,” Eric says.

Finding your way into a stable and supportive community can be a key to recovery. It’s almost too obvious. Jeff Gill, a local pastor who also works with the juvenile courts, believes that the addiction crisis can be linked, in part, to underemployment, to feeling like you’re not contributing to your community. “We have a hopelessness epidemic,” he says. “It used to be that you could see the path up even if you didn’t want to take it. Now it seems like there’s an iron ceiling. By your early twenties, your hand is dealt.”

There are plenty of jobs—the county unemployment rate as of August was 3.8 percent—it’s just that the jobs that are available are often not sustainable, especially for families with children. Amazon has opened a major distribution center in the county, about 30 minutes from downtown Newark, with over 4,000 employees. But with hourly wages that start at $15, and with no fixed-route public transportation in Newark, it’s not the savior that some thought it would be.

The county’s nominal unemployment rate doesn’t give a clear picture of what is happening on the ground, nor does the county’s poverty rate of 12.6 percent or the city of Newark’s rate of 21.8 percent (nationally, it’s 12.3 percent). According to the United Way’s ALICE report, 36 percent of families are barely making it in Licking County. These families are, as a Newark firefighter told me, a dead car battery away from losing a job, a home, and, more importantly, hope.

Princeton University economists Angus Deaton and Anne Case have noted the increasing death rates for working-class whites across the nation, so-called “deaths of despair”—deaths that are the result of economic and social issues that create a perfect storm of disconnection. (The death rates are increasing even faster for black and Latino Americans.) The numbers are especially high in Ohio, where communities are overwhelmed by people who have seen addiction’s devastating effects, but who still believe that transformation, that recovery, is possible. There are many people like Eric, many people fueled by hope and love for their community. These guerrilla warriors—judges, community organizers, counselors, probation officers, firefighters, and a host of grassroots mothers and fathers and people in recovery packing Narcan, the emergency narcotic overdose nasal spray, and a prayer—struggle against the growing numbers.

(Photo: Will Widmer)

But people are thinking creatively to fight the problem. A group called The Addict’s Parents United makes “blessing bags” with self-care products for the homeless and struggling users. Other groups like Save Our Billy, the Licking County Champions Network, and Ohio- CAN (Change Addiction Now), support parents and friends and users themselves with group meetings for parents and faith-based mentorship. The health department created an online training and distribution system for Narcan. And the county’s addiction task force, organized by the Mental Health and Recovery board, brings advocates, social workers, educators, law enforcement, and, really, anyone willing and ready to engage, together for an information sharing and strategizing session every couple of months.

And yet, they’ll all agree, it doesn’t seem like enough. Each of these small efforts feels futile when stacked against the overwhelming odds in a county where many families have not only read about the so-called addiction crisis, but have experienced it firsthand. And, even in the aggregate, the volunteers are already dramatically outnumbered by those they’re trying to help.

Overdose numbers in Ohio are getting worse and health officials across the state are starting to notice a rise in fentanyl mixed with cocaine or meth. It’s not clear if people are buying it for the meth, the cocaine, or for the mixture with opioids. But the numbers are clear. Writing in the Plain Dealer, Dennis Cauchon of Harm Reduction Ohio notes that fentanyl is a serious public threat because it is now killing cocaine users and, he writes, “far more Ohioans use cocaine than use heroin.”

“In the 3,480 Ohio overdose autopsies reported to the state” as of January of 2018, Cauchon writes, “757 of the fatalities were for cocaine and fentanyl versus 476 for heroin and fentanyl.” Cauchon advocates for the use of test strips so that users will know what’s in their drugs.

When I spoke to Cauchon, who lives in Licking County, I used the term “addiction epidemic.”

“No,” he said, “it’s an overdose epidemic.”

For Eric, the overdose epidemic began almost two decades ago, when his sister died from an overdose on crack cocaine, just after he got out of prison. And Johnathon says he has overdosed a dozen times, but survived them all. When a friend died of an overdose last March, he made sure he went to the funeral home visitation. He wanted to pay his respects, but also he needed the reminder of just how close he could have been.

Johnathon didn’t last long at The Refuge. He wasn’t ready for treatment, he said after the fact. He wanted to leave after just 24 hours. So he was driven to the parking lot of a Walmart in nearby Athens, about an hour and a half southeast of Newark. From there, he caught a ride back to Newark, where he was back on the street and back in the trap houses. By early November, weeks after he left The Refuge, he was spending some of his nights sleeping under a bridge. One night, dope sick and tired, he loaded a syringe with antifreeze and contemplated his last move.

He gazed into the darkness of Raccoon Creek, shivering. He could hear the trickle of water, the rumble of cars overhead, and the occasional whistle as trains crossed a trestle a few hundred yards away.

It’s a peaceful place. Trees-of-heaven and birch line the banks, and in warmer weather fish jump; but it’s not without its ghosts. One time Johnathon says he cooked up two grams of heroin—about twice what he would shoot normally at the time—with the intent of taking his life. A guy who was out fishing found him passed out on the muddy bank of the creek.

He didn’t want to go that way tonight. Johnathon put down the syringe and called Colleen Richards, a mother and volunteer for the Newark Addiction Recovery Initiative, a police-run program that lets users turn in their drugs and rigs in exchange for help finding a detox program and, hopefully, a bed in a rehab facility.

(Photo: Will Widmer)

The next morning, Richards and Patricia Perry, another activist who, like Richards, has a child who suffers from substance use disorder, waited for Johnathon to meet them in front of the county library. They were patient, but anxious. They know the stakes are high. If Johnathon shows up and they can get him to detox, this could be the moment that he begins his recovery. If not, it could be the preamble to an overdose.

When Johnathon finally arrived, he was carrying a plastic shopping bag with toiletries. Johnathon is fastidious. Even though he had slept outside, he was clean, with just a slight 5 o’clock shadow. Richards and Perry took him to McDonald’s and told him about the program. He was nervous about willingly walking into a police station.

Before he could go there, he told them, he needed to get well. Perry and Richards waited more than an hour. Eventually, Johnathon came walking down 4th Street smoking a cigarette and wearing a camouflage jacket and jeans, his grocery bag of toiletries over his shoulder. He was hesitant, twitchy. His eyes were squinting.

“Johnathon, I want you to meet Trent Stanford,” Richards said. “He’s a very good friend of mine. A good guy. You are in good hands, young man.”

“We’ve got a care bag for you. It’s got some snacks and socks and clothes and stuff,” Patricia said.

“Do you need anything else?” Richards asked.

“No,” Johnathon said. “You know what I really want? Pumpkin ice cream. I love that stuff. They have it at the United Dairy Farmer in October.”

“Well, we don’t have that, but we can try to get you clean,” Stanford said.

After three days in detox, and no possibility of a bed in a long-term treatment facility, Johnathon called C.J. Wills, a friend of Lee’s and someone also in recovery. C.J. helped Johnathon get a place in a local men’s shelter.

C.J. grew up in Newark and had a hard life. He’s just now getting to the place where he feels he can help others; it seems to give him strength. As a child, there was addiction and abuse in his home. As a teenager, he got caught up in a gang and was drinking and smoking too much. He eventually found his way to meth, and, like Eric, to jail and then to prison. His last stint was for four years.

Once out, he went back to doing the things that he’d been doing before—with the same results. But he desperately wanted to get control of his life and custody of his son, Maddox, whose name is tattooed on his arm and whose childhood handprints are tattooed on his side, a sort of perpetual embrace.

One cold night C.J.’s mother kicked him out after an argument. It was winter, and he had nowhere to go. He pulled his truck over in the parking lot of a church and fell asleep. When he woke, he drove to a trap house to get warm, and he called Eric, who told him to come over immediately. When he got there, the two drank coffee and planned C.J.’s next move. He spent a night or two with friends, a couple of nights at the Budget Inn, and finally landed in an efficiency apartment.

(Photos: Will Widmer)

(Photo: Will Widmer)

And now Eric, C.J., and I are in a coffee shop across from the courthouse in downtown Newark discussing Johnathon. “I’ll tell you this right now,” Eric says, “until he’s ready, all we can do is pray for him. We don’t look him up. We don’t chase him down.”

C.J. says: “When I picked him up at Shepherd Hill, I said: ‘Are you done? What are you gonna do different this time?’ He said he was gonna start going to meetings. He went to one meeting with me.”

Eric leans in toward C.J.: “Now I’m gonna paraphrase Martin Luther King, but he’d say the true testament of man’s character is what he’ll do when no one’s looking or there’s no P.O. or judge, when it’s just your decision. That’s when it’s an impactful moment; you make that decision to turn it over to the will of God. That’s when people move it forward.”

If Eric sounds like a preacher it’s because he is, in a way, preaching the gospel of recovery. He eschews conversations about systems. He focuses on the power of the individual to save himself. But, in truth, systems have shaped his own experience—he had a difficult childhood, found his way to the streets, and then to prison.

He finally got clean when he was 47, Eric says, and it was a personal decision he made in the presence of a supportive and affirming recovery community, a community that abounds in Licking County. There are meetings every day with nicknames like Journey Home, First Things First, and Club Serenity. The bright side, if that’s possible, of the addiction crisis around this country is that it has given, as Eric puts it, a “hope shot” to thousands and pushed people to participate in their communities.

“For me,” C.J. says, “rehab was getting locked up. I prepared myself inside. And you always think you got it. But when I came out, and real life kicked in, I didn’t have it.” He had the desire to change, he says, but he didn’t change the “people, places, and things” that had led him to use in the first place.

“I can tell you this,” Eric jumps in, “you might not think you had it, just like Johnathon, but I really truly believe that he already has everything he needs. He’s got it in him; he just don’t know it. The disease erases everything you have. You do feel like you have to learn it all over again.” He looks over at C.J.: “You already have it. You don’t need me.”

Eric presses: “You already had everything you needed to stay clean for 24 hours. This is all about staying clean for one day. This is not about staying clean for the rest of your life. And if you sat in the jail cell, you know it ain’t gonna kill you to stay clean. That’s because we do what we want to do deep down inside. And if you wanna still use, if you wanna get high, you gonna get high. I don’t give a shit what nobody say.”

Eric’s turning point was when a judge told him he’d have to decide what he loved more, his kids or the drugs. His life had never been presented to him in such stark terms. “I had a moment of clarity,” he says. “Everything up to that point, in that moment—he was right.”

It was March 22nd, 2003, and Eric says that he was so humiliated in that courtroom that he “sort of got clean out of spite.”

(Photo: Will Widmer)

“It’s hard to recover alone and without your community,” Eric says.

This is something that C.J. knows all too well. In a very real way, it was his community and people like Eric who helped him reorganize his life. Now, if he does relapse, he has people to lean on. He doesn’t have one recovery group; instead, he seems to surround himself with a community of support. He has participated in court-mandated programs like Bridges Out of Poverty, Triple P Parenting, and Father Factor, and has had the steadfast support of the head of adult court services, a guy named Scott Fulton. Fulton made C.J. his special case, meeting with him once a week, the two of them making their way through a cognitive behavioral therapy workbook together. Fulton also encouraged C.J. to connect with the Newark Think Tank on Poverty.

Somehow, some way, C.J. has cobbled together this network for his own recovery. But he wants more. C.J. needs a stable job. He’s working construction—it’s not enough. He’s trying to scrape together money to give his son a Christmas. He wants to provide for him, to be there for him. He dreams of one day having a small house on the edge of town, one with a yard where he can throw the football around with Maddox. He wants stability.

The smallest things can throw people off course, especially those living just on the margins. Out of the blue, C.J. gets a bill from the parole board for “unpaid fees.” The bill is for $640. He’s not sure how he’s going to pay for it. He’s depressed; he’s lonely; he’s frustrated.

“I feel like I’m doing everything right,” he says as we sit down in a booth at a Bob Evans, “and now this.”

C.J. and I are meeting up before going to an opioid addiction awareness meeting together. Allen Schwartz from the think tank texted me beforehand and asked if he could join us. When he arrives, he gets straight to the point: He wants to help C.J. He wants to figure out how they can handle this problem together. In this moment of crisis, C.J.’s community steps in, a community of care that he didn’t have before.

In the addiction research community, what is happening here, some might say, is part of a model of addiction recovery called recovery-oriented systems of care, or ROSC. It’s an approach to addressing addiction that seeks to move beyond pathologizing the user as an “addict,” forever marred by that designation. Instead, the focus should be on building the person up so they attain and sustain long-term recovery.

Michael T. Flaherty, a Pittsburgh-based clinical psychologist and consultant in ROSC, says that recovery-focused care should be about building on strengths, increasing “recovery capital.” This can mean using less or abstaining, but it can also mean finding or obtaining better housing, employment, education, emotional and family health, or legal relationships. By increasing one person’s “recovery capital,” he points out, that of the entire community grows. And as this resilience grows, the ability to address an addiction crisis grows.

(Photos: Will Widmer)

(Photo: Will Widmer)

It’s a challenge to build such recovery capital in a place that has its own social and economic challenges—and Newark has them. Despite those challenges, people like C.J. are becoming resilient. C.J. is being embraced by his community, and he’s building a new one.

“There’s no cookbook,” Flaherty says. “It’s highly individualistic. It’s understanding the illness first as an illness, and then accepting that there’s a way you can get over it, and then meeting others like that that you connect to, so it strengthens your sense of self-esteem.”

And then, he adds, in a turn of phrase that resonates, “it’s a positive moving.” In C.J.’s life there is certainly a positive moving.

Johnathon, on the other hand, is holding on as best he can. In June, he went to court; he had been charged with aggravated trafficking, a fourth-degree felony. Right around the time when he had been in the Budget Inn, he bought carfentanil from a notorious trap house. The house was being watched by police, and 39 people were brought up on charges ranging from suspected trafficking to suspected harassing of a witness.

Johnathon got three years probation and 100 hours of community service. As part of his probation, he started going to the Licking County Alcoholism Prevention Program, or LAPP, where he met with a counselor or attended a group meeting once or more a week.

After Johnathon signed a waiver, his counselor let me sit in on a session, where they talked at length about how far Johnathon has come, about a time in the fall when he went off track—he took half a Percocet after a back injury. His counselor wants Johnathon to start thinking about what will replace his opioid use disorder—he’s not sure he’s found that yet—but he has found connection. He has found a way in.

Driving back to his apartment, I ask Johnathon what he thought of the counselor’s concern.

“I just don’t use. I don’t do anything that’s going to put me in a position where I’d want to use. You know what I’m saying?”

“OK.”

“Am I saying that I can’t ever fucking relapse? No, I ain’t saying that. That’s one thing you can’t give an answer to. No. It happens.”

“And you know what could happen if you relapse?”

“Yeah. Therefore, I don’t put myself in situations. I’m still new at this recovery—I don’t have their formula.”

Days after Eric pushes the Newark Think Tank on Poverty to focus on addiction—and to really, truly listen to the addicted—Ohio attorney general and future governor-elect Mike DeWine unveils Recovery Ohio, a 12-point plan to deal with the substance abuse crisis. While it’s framed as combating the opioid crisis, its focus is much wider than opioids alone; it’s on building greater capacity for treatment and prevention. DeWine was a vocal critic of Medicaid expansion and talked about cutting it—a move that would send many in a spiral—though he changed course and announced his support on the campaign trail in July.

(Photo: Will Widmer)

Hopefully, there’s a net to catch them. Maybe that net will be held by overworked social workers and EMTs, police officers, and teachers. Or maybe it will be people like Eric Lee, who don’t get paid for leading Wednesday-night recovery meetings or going to Budget Inns to talk to people like Johnathon or helping young men fresh out of jail find work. Regardless, it will be people who do the work because they believe in it. There’s not much to what Eric does, really. He listens; he connects people to resources; he shares. There’s not much to it. Except, there is. He’s present and supportive. He is check-in, another layer of support for people who need it.

And the think tank is mobilizing as its members begin the work of gathering stories and sharing plans. C.J. goes to an addiction awareness rally outside the Licking County Courthouse wearing a big smile, a blue Newark Think Tank on Poverty shirt, and his beloved Cleveland Browns ball cap. I once asked him how he could root for such a disastrous and frustrating team. He told me that half of his family is from Cleveland, and besides, “they struggle like I struggle.”

C.J. hands out the first issue of Justice, the think tank’s newsletter, with a screaming headline that reads, “We Want Real Treatment for Meth Addiction Recovery.” C.J.’s life has improved dramatically. He now has regular visitations with his son, a car, and a steady job in building services at a local university.

He’s committed to sharing his story, and the think tank is providing a platform. A reporter from ABC 6 News hears C.J. speak up at the rally and asks him for an interview. He tells her about how he was treated as a meth user. He tells her this is an addiction epidemic, not an opioid epidemic—that he’s fighting for all who are suffering. As part of this work, he is collecting signatures for a ballot initiative drafted by the Ohio Organizing Collaborative, an effort to move money away from incarcerating users and toward treatment.

The next morning, C.J.’s alarm will go off at 3:30 a.m., and he will go to work. And when he gets off work, he will go to another meeting with the think tank.

C.J. has a second alarm on his phone that goes off once a day. When it does, he pauses to say, “Thank you, God.” It’s a reminder to be grateful for all he has and how far he has come. He is watching his son grow up. He is taking him shopping for football cleats next week. And he will likely take his clipboard with him, asking anyone he sees to sign his petition.

This is how the battles are fought and how, sometimes, slowly, they are won.

Community Efforts

Five groups successfully fighting addiction in Newark, Ohio, that could serve as a model for others around the country.

Police Departments

Newark Police Chief Barry Connell knows that addiction can be a personal issue for many people, that everyone has a story. He has one too. His story started about 30 years ago on the eastern shore of Maryland, when he cosigned a business loan for his brother-in-law, who then used the loan to start a crabbing business. His first year out, he had a banner season.

Connell says that financial windfall took his brother-in-law, then still in high school, down the road to addiction. He partied. He was exposed to drugs. A star basketball player with plans to go to college transformed into a user who struggled with addiction for the next few decades.

Connell says he feels like he helped finance that use. “I was deeply affected by watching him all those years,” he says. “I can’t write him off. I can’t say: ‘Oh, he’s just an addict. He’s just a junkie.’ I know him. I love him.”

That’s why, in Newark, a user may walk into the police department and seek help. After a brief intake process, a community initiatives officer or volunteer begins the process of finding a detox placement and, hopefully, a more long-term rehab program. So far, the program has served 131 people.

The Newark Addiction Recovery Initiative is modeled on a similar program in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and supported by a national network of police departments that are trying the same thing to varying degrees. It’s a harm-reduction approach that is accepted by many in the Newark community—a politically red city in a red county.

Participants must turn over any drugs or paraphernalia they are carrying. Those with outstanding warrants, who are sex offenders, or who are under 18 and lack parental consent, are ineligible. If they want to back out at any point, Connell says, they may. Initially, the program was intended to serve just those addicted to opioids, but Connell says they are trying to get the word out to those addicted to meth as well.

Some participants have Medicaid, a few have private insurance, and others have nothing. For them, scholarships are available through partnering rehabilitation facilities.

Connell admits that substance abuse disorders are best handled by specialists. At this point, he says, police know “just enough to get us in trouble.” His officers are learning as they go, figuring out how to help people whose abuse masks other, often more complicated, concerns.

Probation Mentors

People often exit jail or prison without a support network. Whitney Babbert, a probation officer with Licking County Adult Court Services, is trying to change that. She would like everyone under her charge to be welcomed by mentors as soon as they walk through the gate.

In many cases, Babbert says, she is the only support system for her clients. Some people battling addictions have frustrated their families to the point that they have turned their backs on them.

Over the past year, she has hatched a plan: training men and women ending probation to act as mentors and allies to those who are just starting out. “It’s structured like NA/AA sponsorship,” she says, “only it’s not just for sobriety; it’s for all of life’s barriers.”

Mentors will help clients access resources to address issues like housing, child custody, mental health, and addiction, and help them navigate the bureaucracies and lend a hand if they slip.

When people leave the jail, Babbert says, “they can either go left or right. They can go left and come here or go right and then across the street straight to the trap houses. [Imagine] if we have someone there to block that and say: ‘Hey, you’re going to be court-ordered to a lot of things. The court is making you jump through hoops like crazy. I’ve been there. Let me help you figure out what services are available.'”

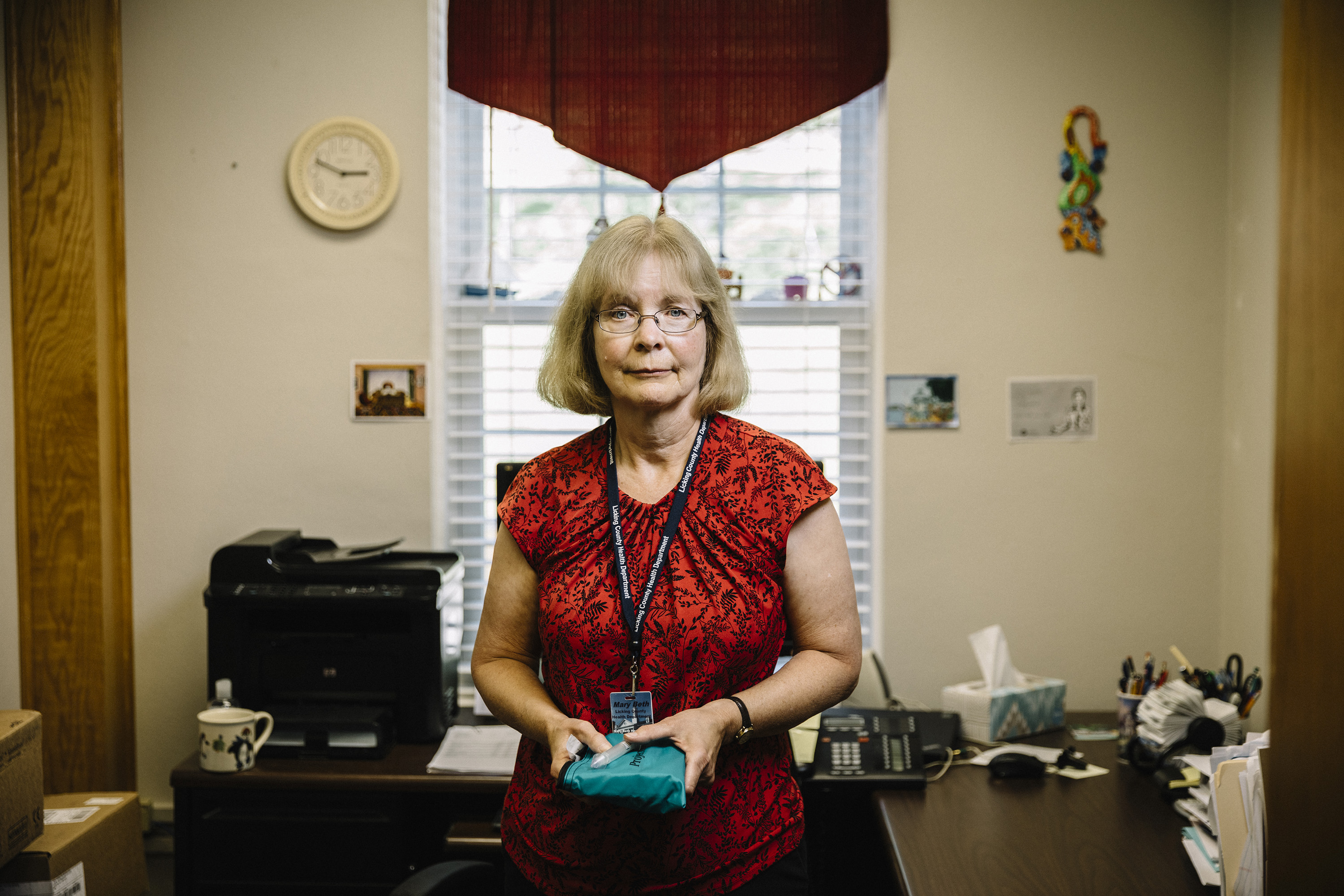

Health Departments

One of the best interventions for preventing opioid overdose deaths is access to naloxone (or Narcan), a medication that reverses or slows down an overdose by blocking the effects of opioids on the brain and restoring breathing. It is available over the counter at many pharmacies in Ohio, but, in Licking County, it is also distributed by the county health department for free.

Licking County began distributing the medication in June of 2016, after receiving a grant from the state called Project DAWN (Deaths Avoided With Naloxone), which allowed the health department to implement a community-based drug overdose education and naloxone distribution program. The department has hosted dozens of opioid overdose training workshops—at its offices, the county library, schools, social service agencies, and a local ice cream factory—and has distributed over 500 naloxone kits.

Workshop participants learn how to recognize the signs of an overdose, how to perform rescue breathing, and how to administer naloxone. The events are free to attend, and participants walk away with their own naloxone kits.

Public-health nurse Mary Beth Hagstad says she knows there was some hostility toward the program on social media, but so far people are appreciative of having greater access to the drug. They want it, she says, because a family member or someone they work with is using. “They’re excited to have access,” she says. “I’ve had a dad and mother come in almost in tears because they’re grateful.”

But the health department also wants to reach people who cannot attend or who do not wish to be seen attending such events, so now it is also offering the training online for county residents in a first-of-its-kind program in Ohio. Participants must complete online training before having the kit mailed to them, and Hagstad is on call to answer questions about the drug.

Activist Parents

About 10 years ago, when Patricia Perry first learned that her son Billy had a substance abuse disorder, she felt desperately alone. She couldn’t find a support group and knew very little about treatment options, and even less about the disease.

A lot has changed since then. She is now part of a growing network of parents and grandparents, siblings and friends, who have become activists in response to the addiction crisis. Perry serves as Licking County coordinator for OhioCAN, an organization that works to “empower those whose lives have been impacted by substance use.”

The group has empowered Perry, who now sends cards to those in treatment or prison, and helps distribute dozens of bags each week full of personal hygiene products (called “U Can Bags”) to those who need them. Perry also runs a homeless outreach program with friend Jen Kanagy, handing out food and clothing to between 50 and 75 people every Saturday. This outreach helps her get to know users and to connect them to resources—work that is deeply personal to her given that, for many years, she says, Billy was homeless. In the future she hopes this project can be a conduit for harm-reduction services by exchanging syringes and giving out Narcan and fentanyl testing strips.

Perry says she finally feels a sense of purpose that she didn’t have 10 years ago. Helping those struggling with addiction is now her life’s work. She wakes up most days before dawn to check her email, to organize her work for OhioCAN, to write cards, and to read up on addiction and pending legislation. In the past year, she has hosted three Narcan trainings, spoken to two Ohio House committees, and organized an awareness rally in Newark.

Perry does all this while keeping an eye out for her son, who is currently in treatment. He still struggles, but now Perry knows she’s not alone in the fight to support him.

Quick Response Teams

In the past in Licking County, as in most places, there has been little follow-up after a non-fatal overdose. That is changing. Now, the Licking County Quick Response Team follows up with overdose victims 24 to 48 hours after the incident. It’s a collaborative effort of local law enforcement and several mental-health, addiction, and poverty-focused organizations.

Currently, only law enforcement and the local hospital refer possible clients to partnering agencies who then alert the team, though anyone in the county can make a referral through the local 211 hotline. They’ve also recently begun providing some limited on-call hours during peak times for the hospital so the QRT can respond immediately in the emergency room to offer resources and support to an individual who has just overdosed. The team coordinates with law enforcement for an initial outreach. And, according to Tara Schultz, clinical director of the Mental Health and Recovery Board for Licking and Knox Counties, peer support is a central component to the team and to this initial contact.

Schultz says the QRT offers “a safety net for people wavering on going to treatment or not.” There’s no time limit for how long they can offer a client support, but if a client enters treatment, the QRT will continue to offer support for at least the next six months.

The QRT responds to non-fatal overdoses and, because the project is supported by federal funding from the opioid-specific 21st Century Cures Act, it can only track people with opioid use disorder, not problems with other substances. “It’s frustrating for me,” Schultz says. “But it provides us an avenue for connecting and collecting information.”

She hopes that the QRT can leverage what it is learning now to create better systems for working with people suffering from addiction, regardless of their drug of choice.