To get to the future, you must leave the coast of South Florida. Head inland on a county highway that penetrates the flat, mind-numbing expanse of the Everglades—past rock mines and cypress stands and faded billboards hailing defunct tourist traps—all the way to the community of Venus, population 1,043.

I’m driving a rented minivan down a long gravel road, my tires creating a rooster tail of dust. The air conditioning stopped working around the limits of Fort Lauderdale, and the van’s interior has become muggy in the March heat. Something I learned rather late in my travel plans is that Florida has no interstate that runs anywhere near Venus. Its major highways tend to meander up the coast—channels of sunshine and commerce—which makes this trip into the state’s industrial core feel a bit like going off the grid, wandering backstage on the great American production that is spring break. Outside the window, there’s a montage of orange groves and decrepit barns, trees bearded with Spanish moss. Clusters of scrawny cattle plod across a withered pasture, swatting flies with their tails.

I glance at my phone, scanning the email I received from a member of the Venus Project earlier in the week. “If you’re early, please wait in or near your car,” it says. “Don’t walk around the land or down to the water as there are alligators.”

After a mile, the road becomes a lunar surface, cratered and wrecked and gray. A colonnade of lush foliage lines the road, at the end of which stands a large gate that reads:

THE VENUS PROJECT.

JACQUE FRESCO AND

ROXANNE MEADOWS.

I hop out of the car and futz with the rusted latch until the gate swings open, and, after puttering down the long driveway, I finally see a group of cars parked haphazardly around a sun-glazed pond. At least 15 people have already arrived, milling around and shaking hands. No alligators are anywhere in view.

I meet a young, hippyish couple from Stuart, Florida. The man, whose hair is speckled with dried paint, nods at me in the brusque, self-assured manner of alpha males everywhere. His companion wears a mirror-plated skirt and ballet flats, her hair blond and sculpted, like the bouffant of a Lichtenstein print.

“So, how’d you guys hear about Jacque?” I ask.

“Zeitgeist, originally,” the guy says.

“Me too! Zeitgeist,” says a gangly man who steps out of the shade wearing Jesus sandals.

I nod decisively even though I have no idea what they’re talking about. The next visitors to arrive are an amiable gay couple in their mid-fifties, decked out in Crocs and sun hats. “This place speaks to our Star Trek-y tendencies, so we wanted to check it out.”

The clouds part, and sunlight bursts through the serrated edges of the overhead palm trees, beaming down at schizoid angles. Geckos dash across the gravel and vanish into the shrubbery. Finally, one of Jacque’s assistants fetches us from the driveway and leads us into the first building of the tour, a futuristic-looking structure made of white plaster and cement, shaped like a portabello cap. We approach a sliding glass door that reads The Venus Project in creamy stenciled letters. Just around the corner is the man we’re here to see.

I first heard about Jacque Fresco via a student of mine who chose to write his final paper about the Venus Project. The student was a hemp-clad kid, one who regularly derailed class discussions with elaborate conspiracy theories about the World Bank or the connections between the Bible and the Chinese zodiac. In his paper, he called Fresco “a modern-day da Vinci” and “the 21st century’s leading social architect of the future.” A Google search soon led me to a Larry King interview from 1974 where Fresco, a self-described industrial designer, detailed his plans for what he would eventually call a “resource-based economy,” a neologism he minted to describe a system where all goods and services are available, free of charge, to everyone. As he told King:

If you took all the gold and all the wealth of this country, all of the certificates of debt and all of the land ownership, all of the diamonds and rings, and dumped it off the coast of Japan, as long as you didn’t touch the American way of thinking, our technology, and our resources, we would not be impoverished at all. America’s wealth is not its gold, is not its banking institutions. These are false institutions. The entire money-structured and materialistic-oriented society is a false society. Ten or 15 years from now, our society will go down in history as the lowest development in man. We have the brains, the know-how, the technology, and the feasibility to build an entirely new civilization.

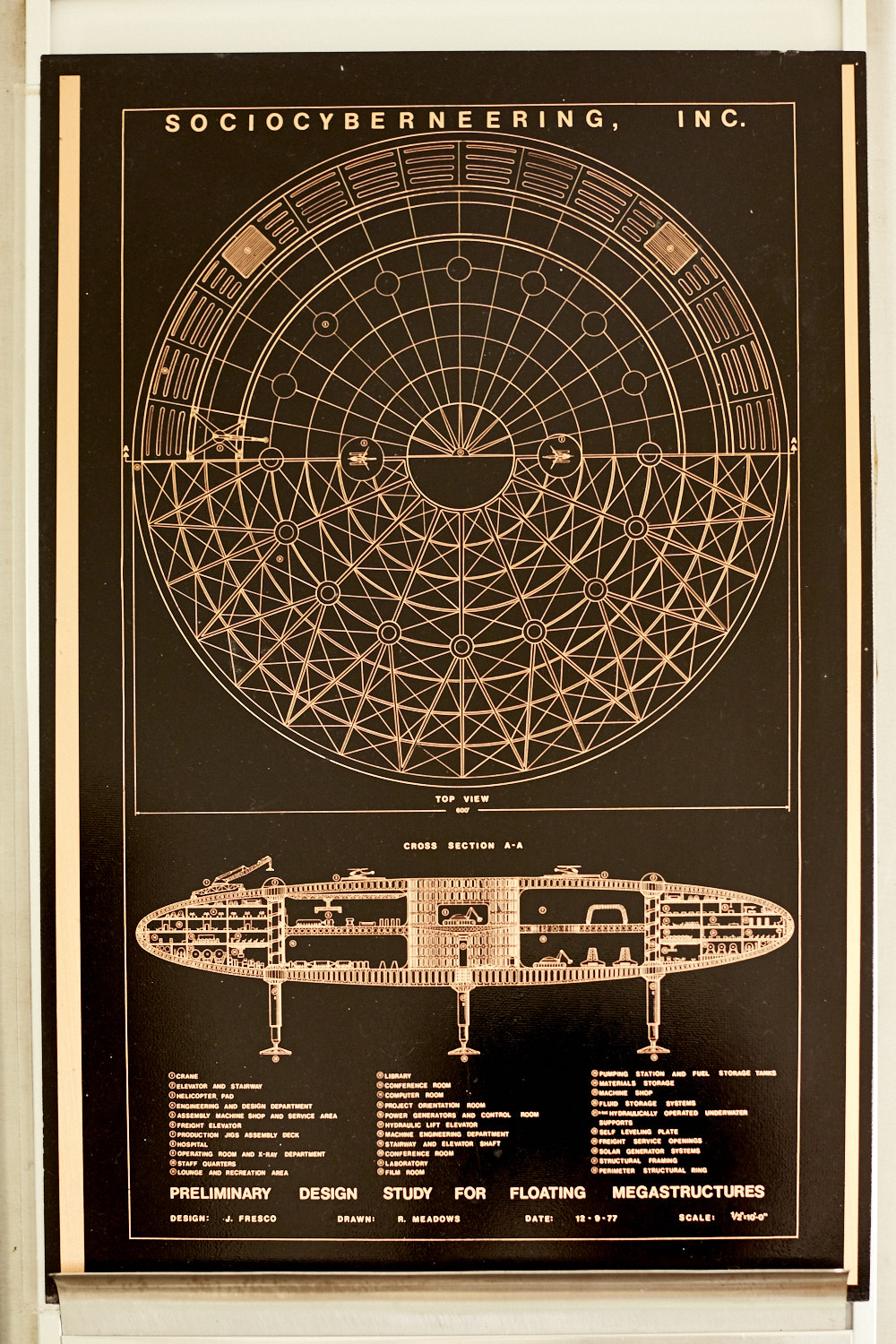

This civilization would be created through “sociocyberneering,” a radical form of social engineering where automation and technology would bring about “a way of life worthy of man.”

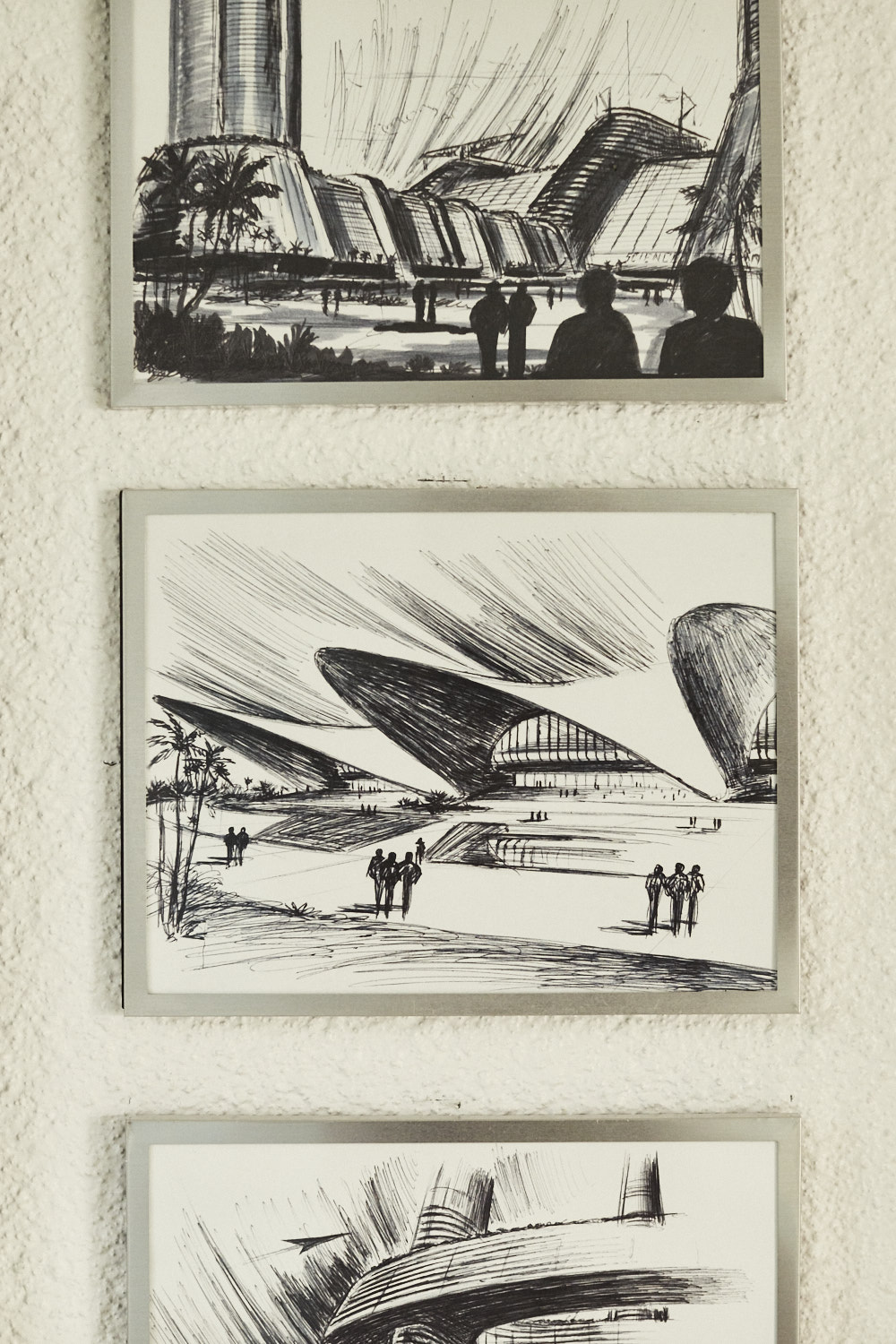

Throughout the interview, Fresco brandished full-color sketches of the future: white domes perched on the surface of the ocean and arranged in concentric circles so as to resemble the structure of an atom. Serving as the city’s nucleus was a central computer, which would monitor the ecology of the region—measuring crop yields in farmland, controlling irrigation, and overseeing hydroelectric power grids. Expanding outward were civic centers, museums, and universities, all of which would operate like public libraries in that any cultural artifact would be available for temporary loan. The next largest ring of the city consisted of a residential area, where denizens would dwell amid opulent gardens and manicured parks, in built-to-suit developments. These elliptical abodes would contain every amenity imaginable (at one point, Fresco predicts the invention of entertainment software that sounds breathtakingly similar to Netflix). The city’s enclosure—the crust of the circle—would house a massive recycling center to which all trash would be ferried via underground conveyor belts. Once there, automated machines would sort the refuse for proper salvaging.

Fresco was gruff and humorless throughout the interview, wholly immune to King’s attempts at playful banter. At one point, he pronounced, “Sociocyberneering is an organization that is probably the boldest organization ever conceived of, and we’re undertaking the most ambitious project in the history of mankind.”

The Internet is rich with lore about Jacque’s origins, most of it adulatory and unnervingly detailed. He grew up in Brooklyn during the nascent days of the Great Depression, and, at 13, he began sketching odd buildings, queer structures, visions of a better world. Perhaps as a coping mechanism to endure the deprivations of his hometown, he drew ritzy glass monoliths with finned roofs and curved walls, which were modeled on the slick architecture from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, a celluloid hit at the time. So advanced were his sketches that a friend of his high school principal arranged for him to meet Buckminster Fuller, the neo-futurist known for inventing geodesic domes. When the two met, “Bucky” was seated in his self-designed Dymaxion car, with its odd teardrop contours, and the young Jacque wasted no time in pressing the famed inventor about “social things,” asking if Fuller ever thought about redesigning the economy, such as giving laborers a greater share of the profits in order to incentivize production. Wise to systemic intransigence, Fuller explained it was hard enough to get a patent and produce a new car, let alone try to upend society. Jacque wasn’t convinced.

Over the next decade, as the Dust Bowl smothered the Great Plains, he hitchhiked across the continent, searching for examples of a more equitable social arrangement. His odyssey eventually led him to an island in the tropics of the Tuamotus, where the system of “natives sharing things,” as Jacque put it, toppled his Western values. When a polygamous chieftain offered Jacque the “best” of his six wives for entertainment and sundry pleasures, Jacque bristled—until he realized that conjugal loyalty was nothing more than a social construct. But it was the tribe’s allocation of resources that intrigued him most. Food wasn’t divvied up based upon rank or status, nor was anyone denied sustenance because of financial lack. Instead, the bounty of the island was apportioned equally to all.

Such observations led Jacque to realize that humans weren’t a bunch of slavering primates who sought to dominate one another, as Tennyson said, “red in tooth and claw.” And despite the prevailing Hobbesian wisdom in the West, life on the island wasn’t nasty, brutish, and short. Rather, Jacque saw that the tribe’s egalitarian behavior was merely cultural, a reflection of its members’ customs and mores, which led him to his signature idea: If we want the Western world to overcome war, avarice, and poverty, all we have to do is redesign the culture.

Despite these quixotic ideas, Jacque spent most of the post-war years engineering consumer products. He designed the first “Trend Home,” a prefabricated residence that could be constructed in eight hours, and established the Scientific Research Laboratories, where he dreamed up a trove of zany devices, such as an umbrella with an electrified disc that could repel rainwater through the polarity of its charge. Some of these designs were featured in Popular Science, Variety, and Popular Mechanics.

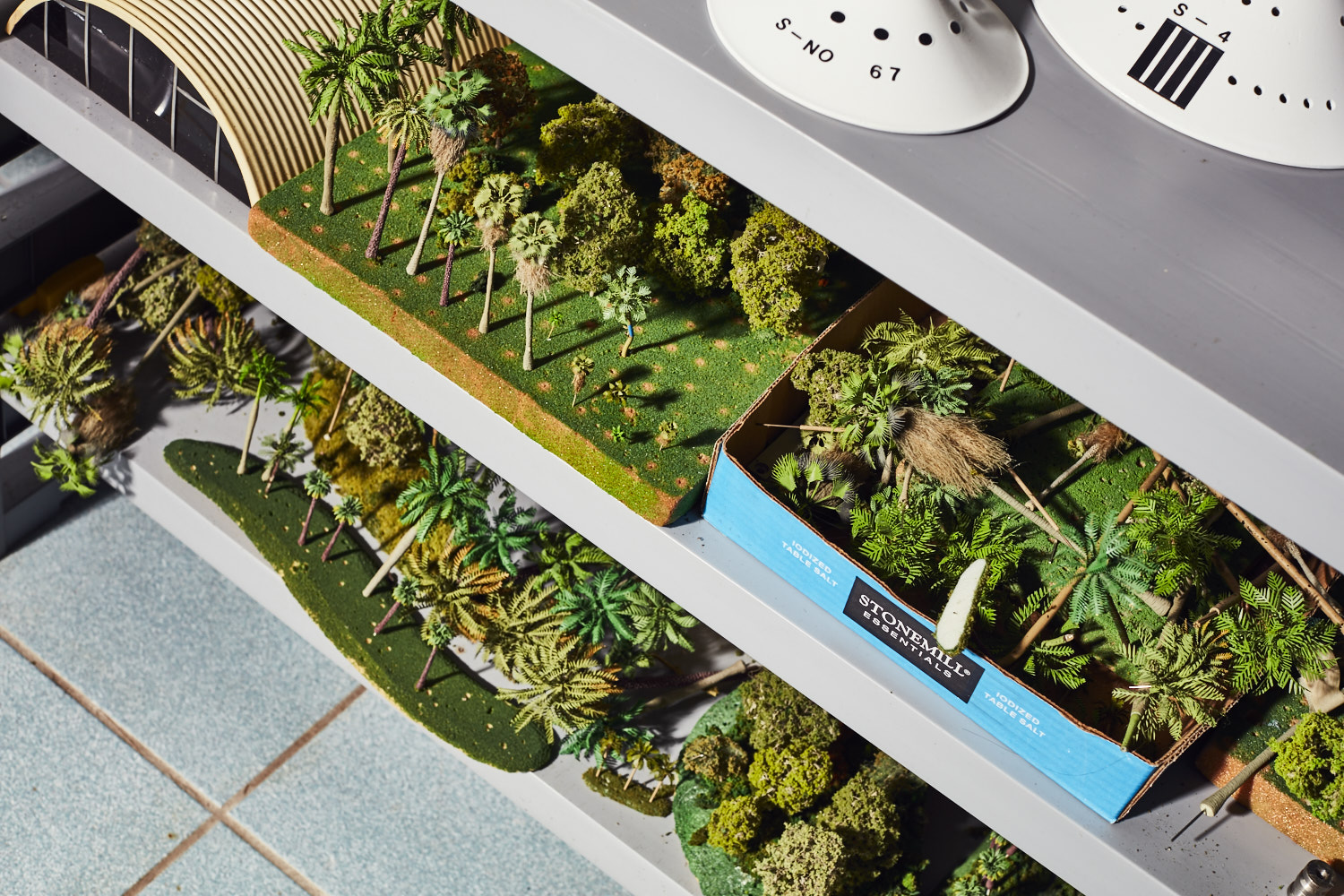

It wasn’t until the 1960s that Jacque finally adumbrated his grand vision for the future. Concerned that most people would remain unmoved by such frothy proclamations, he decided to construct a life-sized model of his ideal city. In 1980, accompanied by Roxanne Meadows, his romantic partner and fellow architect, Jacque purchased 10 acres of land in Venus, Florida, a quaint hinterland just two hours north of Miami. Within a few years, the couple had expanded their land to 21 acres and built several concrete domes on the property, which itself was teeming with cypress trees, exotic birds, and a brood of alligators. Boasting lush vegetation and state-of-the-art design, the estate was meant to stand as the ultimate prototype, the consummate example of what life could look like when you marshaled science and technology toward building an efficient, peaceful society.

I found all of this exceedingly weird and fascinating. But what intrigued me most about the Venus Project was the extent to which the promises of social engineering, so uniformly disastrous when implemented during the 20th century, were suddenly enjoying a revival. Jacque’s ideas were particularly attractive to those Americans who had been left vulnerable by the fiscal tumult of the previous decade. Early in my research, I stumbled across a video of Jacque speaking at an Occupy Miami rally in 2011. Clad in vintage cabana wear—a canvas sun hat and a bone-colored shirt—he told the placard-bearing activists something that struck me as both candid and brave. “Protesting the stock market,” he said, “isn’t going to do anything. I hate to tell you this, but it’s true.” Such remarks led me to believe that the Venus Project might eschew simple transgressive gestures for a more substantial model of an alternative society. Perhaps it would go beyond the hazy objectives of Occupy Wall Street, a movement that did little, in the end, to diminish the brawn of financial capitalism. By the end of the video, I was flooded with questions: What was this resource-based economy, exactly? Could a community really operate without a monetary system? Was Jacque Fresco a genius or a loon, or both? I went to Venus to find out.

After filing into the small foyer of the dome, we fork over a $200 admission fee, a price that, in addition to the seminar and tour, apparently includes “$100 worth of books and DVDs.” We shuffle past a small sideboard table featuring a smorgasbord of nibbles and tidbits—carrots, fruit, and chips—as well as cups of pre-poured lemonade. I’ve been driving for two hours in a sweltering minivan and am perilously light-headed, so I don’t think twice about snagging a sweaty glass and guzzling down the syrupy beverage before I all of a sudden recall the old exhortation you’re apt to hear whenever spending time around particularly charismatic figures: Don’t drink the Kool-Aid.

(Photo: Jarren Vink/Pacific Standard)

The dome is dark and surprisingly capacious, containing 10 rows of chairs that face a tan leather sofa, which is surrounded by a forest of cameras and microphones. On the walls, laminated posters depict the buildings of the future: lozenge-shaped structures that float on pixelated oceans. And yet, despite Jacque’s preoccupation with the world to come, the sad truth is that these printouts look decidedly outdated, on par with the video-game graphics from the Sega CD era.

It’s only after I take my seat that I spot the whiskered eminence himself. Jacque is seated up front on the couch, thronged by citrus-colored pillows, his face partially obscured by AV equipment. This is probably a good spot to mention that Jacque is 99 years old and conspicuously senescent. Aside from his craggy face, he’s garbed in winter clothes—a black leather jacket, dark jeans, matching orthopedic shoes—and sits on two supplementary cushions, presumably for sciatica support and general balance. (In May of 2017, Fresco passed away due to complications from Parkinson’s disease. Roxanne Meadows has since taken over the daily operations of the Venus Project.) While more visitors continue to file in and find their seats, Roxanne—Jacque’s much younger inamorata, a brunette with librarian glasses—announces that we’re about to get started.

After a second, Jacque, who has been sitting there silently observing us, blinking animatronically, finally speaks up. His voice is raspy and quavering: “I’m going to say a lot of things, and some things may bother you, but hear me out.” What follows is difficult to describe. It isn’t so much a sermon or address, but rather a fusillade of provocative statements, some of which sound like a George Carlin riff, while others resemble the CliffsNotes to Cultural Relativism 101. Here’s Jacque on innate human talent: “Nobody has any gifts, you reflect your culture.” On creativity: “There is no such thing as human creativity.” On Christianity: “It’s a wonderful idea, when are they going to put it into practice?” On the slipperiness of the English language: “Bullshit has nothing to do with the shit of a bull.” On God: “They made God into the ultimate control device to tame stupid people.” On the vagaries of human sexuality: “If a boy is raised by six women, he’ll reflect the worldview of women and become a homosexual.” On freedom: “You aren’t free. You can’t yell ‘fire’ in a theater, so how could you be free?” On beauty: “There is no such thing as a beautiful woman.” On the Ku Klux Klan: “I dissolved the KKK in Miami.” On the Western fetishization of female erogenous zones: “When you stroke the dog, you don’t stop at the balls. You stroke the whole dog.”

As far as I can tell, this speech is meant to recreate the lightning-bolt moment he experienced while visiting the Tuamotus natives—if you can recognize that your behavior is learned, your cultural customs are arbitrary, and your social structures are man-made, you can begin to imagine alternatives. Like any good firebrand, he wants to shake up the Etch A Sketch of our worldview, erasing any trace of conventional wisdom.

After an hour of these free associations, Roxanne intervenes, reminding Jacque that he should probably explain the Venus Project’s central ambitions. Quickly, he shifts into autopilot and delivers a scripted lecture on the pillars of the resource-based economy, a truncated version of the more sweeping utopic vision he put forth in his 2002 book The Best That Money Can’t Buy: Beyond Politics, Poverty, and War. “Simply stated, a Resource-Based Economy,” he writes, “uses existing resources rather than money, and provides an equitable distribution of goods and services in a humane and efficient manner for the entire population.” In this imagined world, the conditions of social and political life will not follow the erratic whims of the free market, but will be dictated by the irrefutable tenets of science. By using “cybernated systems” to monitor the planet’s resources, this society would supposedly bring an end to the toxic practices of scarcity and market speculation, thereby obviating the need for political institutions. All of the vital decisions about the direction of society would no longer be clouded by partisan fervor, but would be determined instead by a system of intelligent machines making passionless, algorithmic choices. “The fact that machines have no emotions,” Jacque has written, “in some ways makes them superior to human systems.”

Comments like these, for me anyway, serve to darken the sunny, building-a-better-tomorrow aspect of the Venus Project’s message. Beneath Jacque’s airy ruminations about our post-capitalist future, there lurks a sniffy detestation for most human beings, whom he has regarded, both in print and in person, as irrational half-wits driven by greed and crass desire, an opinion that extends even to the members of his family. In a 2011 interview with The Orlando Weekly, Jacque described his parents as “normal,” which is to say, “fucked-up by society…. They knew nothing. I looked at them as children, pissants.”

Because logic and reasoned argument cannot penetrate such minds, Fresco wants to re-engineer the social landscape so that individuals will be impelled to act rationally, even if they aren’t aware of the degree to which they are being nudged. This underscores one of Jacque’s central tenets: “Build it into the design.” The hope is that, by constructing a gadget, a building, or even a city in a certain way, you can elicit predictable social behaviors. For instance, instead of trying to convince people to monitor their water usage, you could design a bathroom where used shower water is automatically repurposed to fill the basin of a toilet. Likewise, exercise could be incorporated into the layout of public schools as a means of curbing childhood obesity. Rather than instituting sumptuary rules about vending machines or cafeteria menus, administrators could build schools on the crests of steep hills so that students would have to perform gut-busting climbs each morning.

Midway through this speech, when Jacque grumbles something in passing about the inefficiency of the military, a lanky blonde man in aviator shades raises his hand in the front row. “Can I say something real quick?” he asks in a thick Texan drawl. “Can I just tell you about how wars are run these days?”

To my surprise, Jacque nods, yielding the floor. The Texan explains that he’s an Iraq War veteran and has witnessed firsthand the greed and truculence of our country. He suggests our protracted battle in the Middle East is nothing more than a self-fulfilling prophecy, where every enemy casualty only spawns a growing pool of combatants, since the kinfolk of these slain soldiers invariably respond by taking up arms and seeking vengeance. The soliloquy closely resembles the argument of Jeremy Scahill’s 2013 documentary, Dirty Wars, which reported on the practice of clandestine assassination in Afghanistan and Yemen and argued that this strategy did more to perpetuate violence and mayhem than it did to create lasting stability in the region. But something about the way the man describes it now makes the whole idea sound a little nutty, just another conspiracy theory.

Roxanne is the one to step in, interrupting the Texan’s speech and opening up the floor for a Q and A. Jacque’s hearing aids have been on the fritz, so she’ll be “interpreting” our questions for him. Given the futuristic vibe here at the Venus Project, I assume this will involve a system of high-tech gizmos, but in the end Roxanne just relays our queries by leaning over and shouting them into Jacque’s ear at alarming decibel levels, with the frustration of a hospice nurse.

There isn’t much to say about this colloquium. Despite Jacque’s repeated assurances that his plan for the future is comprehensive and practical, the project’s underlying logic is revealed as decidedly muzzy when exposed to scrutiny. When one visitor wonders whether the Venus Project would ever form an army to protect the city from outside aggression, Jacque says the “people of the future” will be rational and therefore won’t engage in such brute behavior. When she clarifies that she’s referring to people who might see themselves as enemies of this society, Jacque replies that the dazzling wonders of the new cities would thwart any unwholesome invaders.

Other visitors stand up to introduce themselves. There is a 20-something musician who incorporates Jacque’s lectures into his songs, a Mexican documentarian who hitchhiked here just so he could videotape the seminar, which he hopes to screen for the citizens of his hometown. There is an Australian nurse who was drawn to the Venus Project after treating hundreds of people sick from contaminated well water.

A few of these visitors allude, in their questions, to the mysterious Zeitgeist, name-dropping it with a kind of insider familiarity. Later I’ll discover that Zeitgeist is a trio of documentaries that suggest, among other things, that the historical Jesus never existed, that the New World Order coordinates all global events, and that the attacks of 9/11 were orchestrated by the government in order to squash civil liberties and foment the War on Terror. The films are the handiwork of Peter Joseph, the founder of the Zeitgeist Movement, a band of dissidents who want to replace capitalism with a resource-based economy. The second Zeitgeist film came out in 2008, and some critics have traced its popularity to the fact that its release coincided with the crash of the housing market, a time when many Americans were suffering, in very real ways, from the wanton excesses of capitalism. Late in the film, when discussing possible alternatives to the market, Joseph cites the Venus Project as an exemplar of a post-scarcity economy.

It’s clear that the Venus Project has become a haven for disenfranchised individuals—veterans cast aside by the country they served; college graduates saddled with eye-popping debt; homeowners lured into toxic mortgages and eventually forced to foreclose. For those who’ve suffered the worst of this bleak fiscal landscape, the Venus Project presents itself as an escape hatch out of a system they feel powerless to change.

Many visitors are anxious to know what they can do to bring about the world promised by the Venus Project. What can they do on an individual level? How can they get their communities involved? On this point, Jacque and Roxanne are oddly blasé. They insist the new world will not come about until a majority of people are convinced of its necessity. It will take some kind of major disaster, natural or economic, to get everyone on board. “All we can do is spread the word,” Roxanne says. She notes that anyone who wants to become a Venus Project ambassador can sign up to receive more information.

Several folks are visibly disappointed by this tepid prescription, especially since a large bloc of them seem like pilgrims who’ve come here to receive a call to action from their beloved guru. Later, once we’ve migrated outside, I will notice the Texan smoking in the fulsome shade of a cypress tree, where he has donned a droopy safari hat. Pinching his cigarette in the three-fingered manner of someone sipping from a joint, he tells a crew of visitors that, despite what Jacque has said about waiting for the free market to collapse, he really wants to “get something started right now.” He encourages the people around him to swap contact information.

Of course, not everyone here fits the mold of the disenfranchised pilgrim. There is also a brand of visitor that seems remarkably more cynical—the gay couple from Fort Lauderdale, for example, or a cluster of young people dressed fashionably in sundresses and fedoras who spent the entire lecture covertly snapping photos of the eccentric décor. As far as I can tell, these are the two sides of the Venus Project’s demographical coin: disillusioned citizens seeking political guidance and wealthy tourists hunting for kooky fun. As the Texan begins collecting information from people, the divide between novelty-hunter and true believer becomes painfully clear. The couple from Stuart shows enthusiasm, but the men from Fort Lauderdale swiftly turn their backs, barely suppressing their amusement.

It is easy to reject the Venus Project as nothing more than the doodles of a wizened crank, an impractical blueprint for an impossible way of life. To give into such skepticism, though, is to ignore the extent to which the concept of social engineering has served as the bedrock of our country. The founding fathers often relied on Arcadian language to describe the American experiment—”the city upon a hill,” “the empire of liberty”—and many of the colonies were founded as utopian societies. Indeed, America presented itself as a tabula rasa for British Enlightenment thinkers who wanted to construct new social systems, which had been difficult to implement in their own country.

Georgia, for example, was established in 1733 by James Edward Oglethorpe, a member of British parliament who appears to have been inspired by the seminal utopian text The Commonwealth of Oceana. Oglethorpe designed the city of Savannah as a matrix of rectangular wards—with farmland on the outskirts, residential lots in the middle, and a commons at the center (a plan that bears a striking resemblance to Jacque’s own proposals for the future). The colony was one of the first where social equality would be accomplished through comprehensive urban design. Profits that exceeded a certain figure would be recouped and invested in communal projects. Slavery was outlawed, as was alcohol. So ambitious was this plan that John Burton, a theologian and one of Oglethorpe’s most trusted confidants, believed that Georgia would “seem in a literal sense to begin the world again.”

Colonial America would ultimately host several other planned communities, but it wasn’t until the Progressive Era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that utopians would institute social engineering on a national scale. At the time, the United States was swept up in “an efficiency craze,” where experts were counted upon to redress every social problem by eliminating waste and deficiency. Historian Samuel Haber has contended that, as the old haunts of God and spirituality were gradually exorcised by scientific reason, many Americans were in the midst of “a secular Great Awakening,” replacing the Christian principle of “goodness” with the modern virtue of “efficiency.”

Yet few people noticed the fascistic mindset lurking below the chirpy promises of social engineers. Blind deference to experts, after all, would give rise to authoritarian regimes. Even the U.S. would flirt with more radical forms of social engineering. In the 1927 Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell, the justices ruled in favor of negative eugenics, which allowed states to carry out compulsory sterilization of “feeble-minded” citizens. Perhaps swayed by the tides of the moment, the ruling was made in the name of efficiency. “It is better for all the world,” wrote Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, “if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.”

This vexed history of social engineering meant that, for decades, the term carried dark affiliations. Even Jacque and Roxanne are hesitant to use it, preferring instead “sociocyberneering.” In fact, when someone on the Venus Project tour asks about “social engineering,” Roxanne lets out an airy, pressurized laugh and looks suddenly flustered. “You know, that term makes a lot of people nervous, because we tend to associate it with communism.” With the agility of a seasoned politician, she adroitly pivots into a discussion about how the Venus Project differs from Marxism, never really answering the question.

But the truth is that now, after decades in which social engineering was dismissed as undemocratic, many Americans are welcoming the idea. B.F. Skinner’s theories on behavior modification, which were once deemed methods of brainwashing, are now enjoying a renaissance among pop scientists and academics. Similarly, Daniel Kahneman’s book on the psychology of judgment, Thinking, Fast and Slow, has become something of a vade mecum for policymakers hoping to sway public behavior. As technology and big data increasingly become part of the government’s toolbox, it’s easy to imagine a time when policy decisions will be determined not by consensus, but through the “objective” best-case scenarios generated by algorithms.

Some have even suggested that the U.S. follow the lead of countries like Singapore, which uses mass surveillance and predictive analytics in an attempt to create a more harmonious society. Several U.S. officials have visited the island in recent years to study the country’s “curious mix of democracy and authoritarianism,” according to Shane Harris of Foreign Policy. More than anything else, these American diplomats are interested in Singapore’s Risk Assessment and Horizon Scanning program, which helps avert terrorist attacks and other so-called “future shocks.” The program also engages in social engineering—developing procurement cycles, making economic predictions, and building curricula for the nation’s schools—and trawls the social media posts of ordinary citizens to measure the potential for popular unrest.

Most Singaporeans are remarkably unperturbed by this program, and perhaps it’s easy to see why. The virtue of social engineering, after all, is its promise of moral relief. The citizen doesn’t have to entertain those pesky questions of rightness or wrongness anymore, since the very armature of the social landscape nudges her toward the “right” choice. Questions about ethics once required an atmosphere of contemplation and debate. But in the eyes of social engineers like Jacque such activities are frivolous and inefficient, just so much pointless theorizing. Now the moral realm is simply a matter of data and design. In the end, it’s hard not to notice the resonance between this yen for greater social control with, say, the emergence of authoritarian leaders like President Donald Trump. When so many Americans feel helpless against the volatility of the market and cannot compete with lobbyists for the attention of their elected officials, it’s no wonder they are willing to surrender their liberties in exchange for the safety and certitude of social control.

Outside, the sun’s molten glare makes the landscape seem blanched and depthless. It’s 90 degrees, and the air is sodden and hot, not unlike the innards of a just-removed mitten. Roxanne appears and leads us on a tour. Speaking with the enthusiasm of docents everywhere, she chronicles the early history of the Venus Project, dispensing nuggets of information at every turn. Initially, she and Jacque considered buying one of the Exuma Islands in the Caribbean, which were too expensive, so they decided on the land in Venus for only $16,000. Since then, they have occasionally completed freelance architectural gigs to cover the cost of new renovations.

As we walk around the grounds, it becomes clear that the campus is in a gradual state of decay. The lawns are withered and yellow. The pool, which on the website appeared to be a limpid sapphire, is actually a scummy green, fetid with vegetative rot. Earlier, when Roxanne spoke of the Venus Project’s dire financial straits, I assumed this was a fundraising ploy, a subtle form of busking. Now, though, it’s obvious Jacque has fallen on hard times or, at the very least, has had to cut back on horticultural upkeep.

Approaching the first dome of the tour, which is a model home, Roxanne confirms my suspicions, saying that, while she and Jacque wanted to expand the Venus Project, all of their plans have been stymied by the miserable fiscal climate.

Inside, the dome is furnished with retro-looking sofas and kitchen stools built into the wall. It’s a vision of the future conceived in the 1970s—The Jetsons meets Soviet futurism. A kidney-shaped breakfast island demarcates the start of an efficiency kitchen, and huge portholes let in mote-ridden tunnels of lemony sunlight. Roxanne tells us the dome is meant to approximate what most residences would look like in the future, noting that the white concrete exterior helps keep the home well-insulated and cool.

Despite these reassurances, the inside of the dome feels every bit as humid and sweltering as the swampland outside. Mosquitoes blitzkrieg us in dark swarms, and everyone starts swatting frantically until little asterisks of squashed bugs constellate our shirts. Roxanne apologizes for the pests but explains that we’re in swamp country, so there’s little she can do. While I would normally accept this brand of fatalism, I find myself more than a little irked. If the whole point of the Venus Project is to marshal science and technology toward optimizing human life, can’t somebody around here cook up a simple bug zapper?

Already, the Venus Project has proven to be a mighty disappointment. To my mind, the success of any alternative vision for society rests in its ability to instantiate those utopian aspirations expressed so elegantly in its pamphlets and propaganda. While Jacque may have constructed a sleek and neatly appointed estate, none of the buildings on campus actually conduct the operations of a resource-based economy. There’s no farmland generating edible crops. There’s no omniscient central computer monitoring the ecosystem of the region. Even Jacque’s bathroom appeared to be your standard, run-of-the-mill lavatory with conventional plumbing, failing to incorporate the central tenet of his own architectural approach: building it into the design. The Venus Project thus stands as nothing more than an overpriced museum, a collection of relics from the career of an inventor who once harbored Icarian ambitions but has now retreated to the outskirts of Florida, living out his days in gruff dismissal of the system.

As we’re returning to the Venus Project’s headquarters, I notice another visitor’s backpack, the front pocket of which reads Facebook in stitched white letters. The man wears a Hawaiian shirt and Hawaiian shorts, although the bottoms have a different motif and color scheme than the top, which makes him look like a parody of tourism. But it’s the backpack that throws me. Perhaps he’s just an ordinary guy, a big fan of social media who shills for the company whenever he has things to tote? But does Facebook really have its own line of apparel? What gives? I pick up the pace and, upon approaching him, ask whether he works for the social network, if he’s a congregant in the House of Zuckerberg.

“Yes,” he says, with great formality and evident pride. “I work for Facebook.”

He says that he and a friend came all the way from California just to visit the Venus Project. They flew into Miami last night and are leaving later this evening. “You know, it’s funny,” he says, “Facebook is actually doing a lot of the things Jacque talks about.”

He explains that the company has started providing free Wi-Fi access to developing countries through its Free Basics program, which connects people to the Internet in places like Africa and southern Asia. Facebook has also been developing drones that could eventually beam Wi-Fi to rural areas. The way he presents it, the project sounds like an act of corporate philanthropy, one that will improve the lives of millions—perhaps even billions—of people. There’s a triumphant pitch to his voice, a barely repressible giddiness at the fact that Facebook can speedily address the digital divide with a simple automated solution.

I happen to know something about this project, and what he doesn’t mention is that some critics have pilloried this endeavor for violating net neutrality. The program was initially designed so citizens of these impoverished countries could only browse the Internet through a Facebook-controlled portal, conveniently allowing the company to expand its data market while limiting access to other sites. Mark Zuckerberg has argued that these criticisms are unfair and idealistic: “We have collections of free basic books. They’re called libraries,” he wrote in the Times of India. “They don’t contain every book, but they still provide a world of good.” Facebook has since expanded the program to websites that meet its technical criteria, though the service remains a walled garden.

Projects like these are, of course, a more immediate and realistic glimpse into the future: one in which the latest technology is harnessed not in the service of utopian communalism, but rather for profit. If anything, Facebook’s presence here at the Venus Project draws into clarity something that has been bugging me all day. It may well be that Jacque’s brand of technological solutionism—to borrow Evgeny Morozov’s term—sounds so familiar because it recalls the dogged optimism of Silicon Valley, an unwavering belief that we can code our way toward wealth and ethical perfection. Just listen to Marc Andreessen, a Menlo Park venture capitalist, wax grandiosely on the Valley’s vision for the future:

Posit a world in which all material needs are provided free, by robots and material synthesizers…. Imagine six, or 10, billion people doing nothing but arts and sciences, culture and exploring and learning. What a world that would be….

Historically, social engineering has been the preferred strategy of utopians looking to overthrow capitalism. But Silicon Valley presents a rare case where private corporations have taken up the mantle of designing a better tomorrow—albeit not for its citizens, but for its customers. Scads of smart technologies have been released over the last decade, promising to nudge customers toward ethical behavior. In his book To Save Everything, Click Here, Morozov, a strident critic of Silicon Valley, examines a research project called the BinCam. This invention outfits an ordinary trash can with a smartphone that takes pictures of the bin’s contents whenever the lid is closed. Workers for Amazon’s Mechanical Turk program then review each photo, determining whether any of the discarded items could have been recycled. This info is then automatically posted to the person’s Facebook page and given a conservationist score, allowing users to compete with each other.

On the surface, BinCam seems like an ingeniously playful solution to the problem of shoddy recycling. But embedded within the product are a whole host of dubious ethical assumptions, which Morozov proceeds to interrogate: “Should we get one set of citizens to do the right thing by getting another set of citizens to spy on them? Should we introduce game incentives into a process that has previously worked through appeals to one’s duties and obligations? … Will participants stop doing the right thing if their Facebook friends are no longer watching?” What Morozov doesn’t mention, of course, is that the real motivation behind this kind of project isn’t conservation or social justice. It’s profit. Beyond whatever minor conservation efforts BinCam might foster, the gadget’s chief function would be to dig through your trash and determine which products you buy and at what frequency, thus enabling it to more effectively sell your information to advertisers.

If nothing else, Facebook operates as a classic example of the ways in which Silicon Valley cloaks its economic motivations beneath the jargon of altruism. The company bills its features as convenient ways of staying more intimately “connected,” but seldom mentions that it tracks consumer habits across a lifetime or that Open Graph stalks users around the Internet even when they’re not on Facebook.

From the podiums of tech conferences, luminaries from Silicon Valley often adopt the rhetoric of revolutionary utopians. They insist that the doctrine of disruption can guide us toward moral betterment, that social ills are actually just “engineering problems.” Several Menlo Park investors have even taken a page from Jacque Fresco, specifically his designs for nautical cities. Back in 2008, Patri Friedman—grandson of Milton Friedman—established the Seasteading Institute, an ocean-based community that wants to experiment with alternative social and political systems. According to The New Yorker, the project received a $1.25 million investment from Peter Thiel, the outspoken libertarian and former chief executive officer of PayPal, who hoped, along with Friedman, to capitalize on the United Nations’ lax maritime laws and explore new governmental frameworks, including those of pure, unregulated capitalism. One potential model was something Friedman called “Appletopia,” which he told Details would allow a corporation like Apple to found its own country. And they aren’t the only tech folks with these ideas. In 2013, the entrepreneur Balaji Srinivasan called for Silicon Valley to secede from the union. This “Ultimate Exit,” as he termed it, would require programmers and venture capitalists of the West Coast to “build an opt-in society, ultimately outside the U.S., run by technology.”

Of course, the relevant difference between the Venus Project and Silicon Valley is that the latter group actually has the money to carry off such a project and thus has little incentive to abolish the free-market system. Utopian rhetoric aside, these tycoons are not about to endorse a resource-based economy. In such a climate, to think that technology and good design are the last bastions against the bruising effects of financial capitalism would be a grievous misapprehension. If anything, these moguls want an even freer exchange of capital and ideas, untrammeled by oversight or regulation.

Our tour ends where it started. When we return to the dark dome—the Venus Project’s headquarters—Jacque is waiting for us, still positioned atop his cathedra of pillows. Everyone is glazed with perspiration, and the heat has spawned a sudden camaraderie, prompting all of us to help out in the common cause of cooling off. One Venus Project staff member arranges a fan to oscillate across the first few rows of chairs, and a few female pilgrims help Roxanne fetch more glasses of lemonade. For a minute, you can almost imagine what it would be like to live here, with everyone cooperating like a motley von Trapp family, a cheery symbiosis worthy of song.

Many of the visitors want to have their picture taken with Jacque, so they queue up like congregants waiting to receive communion. The rest of us settle into our chairs. A few of the fashionable kids brandish their smartphones and begin flipping through the selfies they’ve taken while on the tour, posting the most flattering ones to Facebook and Instagram. Tendrils of sweaty hair are plastered darkly to one visitor’s forehead. Another’s cheeks are sun-scorched and crimson. After six hours here at the Venus Project, all of us are beginning to display the sleepy lassitude of the heavily medicated.

I take a final look at the people around me. Here is the poor musician who incorporates Jacque’s lectures into his songs. Here is the Mexican documentarian—wearing a Stetson hat over long, raven-colored hair—who hitchhiked here just so he could videotape Jacque’s seminar. Here is the Australian nurse, her arm thrown over Jacque’s shoulder, smiling plastically into the flash of a smartphone camera. And here is the Texan, gesticulating wildly, telling another visitor about the resource-based community he wants to establish in Nicaragua. These pilgrims—each forsaken by our system, each longing for a brighter future—have come to the backwater fringe of Florida, searching for a vision of society where their grievances will be addressed, where the injustices they’ve faced will be acknowledged and treated with swift remedy. And yet as dusk falls over Venus, Florida, I can’t help but wonder who, in the end, will profit from this spirit of discontent.

A version of this story originally appeared in the December/January 2018 issue of Pacific Standard.