There is a word, sad and resonant, for the last member of a dying species. The word is endling. Martha, who perished at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914, was the endling for the passenger pigeon—the final representative of a bird once so prolific its flocks blackened the sky. The Tasmanian tiger’s endling, Benjamin, froze to death in the Hobart Zoo one night in 1936, when his keepers accidentally locked him out of his enclosure. Lonesome George, the last Pinta Island tortoise, expired peacefully in 2012, at around 100 years old.

It is entirely possible that the endling for a bashful porpoise called the vaquita is today swimming somewhere off the Mexican coast. Vaquitas dwell exclusively in the Gulf of California, the tongue of the Pacific Ocean that laps the Baja Peninsula, in a tiny pocket of turbid sea that could fit three times within Los Angeles and its suburbs. At just five feet long, vaquitas are the world’s smallest cetaceans, the order that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. They eat fish and squid, which they locate with high-frequency clicks. They avoid the rumble of boat engines, prefer traveling in inconspicuous duos, and refrain from jumping, splashing, or slapping their tails. They are a headache to study. For all their secrecy, they are adorable—endowed with a snub snout, fetching dark eyepatches, and black lips whose coy smile, researchers have written, recalls a marine Mona Lisa. Cross Flipper with a very shy panda and you’ve bred a vaquita.

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

Although the Mexican fishermen who began plying the upper Gulf in the early 1900s occasionally encountered it, the vaquita—Spanish for “little cow”—wasn’t officially recognized as a species until 1958, after scientists deduced its existence by examining odd skulls that had washed ashore. We know less about the vaquita’s habits than we do about practically any cetacean’s. Among the first people to survey Phocoena sinus was Bob Pitman, an ecologist who has seen more whales, dolphins, and porpoises than perhaps any person on Earth. In August of 1993, Pitman sailed into the upper Gulf on a ship called the Ocean Starr to track common dolphins. When the Ocean Starr crossed paths with two vaquitas, he convinced its captain to follow. For several days, the ship motored back and forth across the Gulf, its crew scanning the surface through binoculars for the vaquitas’ black, triangular dorsal fins. On August 11th, Pitman saw 25. “I think there is a good possibility,” he told me, “that no one will ever see that many in a single day again.”

In the years since Pitman’s survey, the vaquita, never abundant, has entered a tailspin that is almost certain to end in its demise. In 1997, nearly 600 vaquitas swam the waters of the Gulf. A decade later there were 250. Then there were fewer than 100. Then 60. A 2016 report warned that the vaquita was “racing toward extinction”; a 2017 follow-up lamented that the collapse had “continued unabated.” Today, fewer than 30 vaquitas remain. They are the world’s most endangered marine mammal. “Every time I see one,” Pitman told me, “I wonder: Is this the last one I’m going to see? Is this the last one anyone’s going to see?” Like most people invested in the porpoise’s survival, he often sighs heavily. The word intractable is a fixture of his vocabulary. “We talk about extinction as a glib abstraction. But it’s real, it’s happening, and vaquita are next in line.”

The damnedest thing about the conundrum is this: If ever an endangered species should be easy to save, this is it. Vaquitas are cute and, in their own introverted way, charismatic. They lack salable tusks, pelts, or meat. We know exactly where they live: not in some distant corner of Asia or Africa, but in our backyard. You can rent a car in San Diego in the afternoon, as I did, cross the border at Calexico, and arrive in vaquita country in time to eat dinner at a restaurant called, of course, La Vaquita.

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

Vaquitas, unfortunately, are collateral damage. They share their habitat with a fish called the totoaba, a mammoth cousin of the sea bass whose swim bladders are a delicacy worth up to $100,000 per kilogram in mainland China and Hong Kong. Although totoaba fishing has been banned since 1975—they, too, are critically endangered—poaching is rampant. Vaquitas, roughly the same size as totoabas, are prone to getting entangled and drowning in illegal nets. Demand for totoaba bladders soared in 2008, driven by an influx of cash into the Chinese economy; the dried organs became popular investment vehicles, a commodity as fungible as gold bars. Seventy-five hundred miles away, Mexico’s black market erupted. Scientists, fishermen, and tourists soon began finding beached totoaba carcasses with the bladders cut from their bellies, meat left to rot. “Prices now are higher than cocaine,” Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho, the Mexican biologist who chairs the vaquita recovery team, told me in the spring of 2017. “It’s madness.” That year, conservationists recovered 396 nets from the upper Gulf—48 tons of illegal gear.

As poaching surged, so did vaquita bycatch. Between 2008 and 2015, 80 percent of the world’s vaquitas vanished—hauled up dead by fishermen, dumped surreptitiously back into the ocean. Biologists went two years without spotting a fin. The government, frantic, suspended all gillnetting in 2015, a measure that shut down a $50 million legal fishery for shrimp and fish but failed to stem poaching. American conservationists proposed a boycott on Mexican seafood to compel tougher enforcement. Miley Cyrus and Leonardo DiCaprio passed the hat on vaquitas’ behalf. Some fishermen, ruined by onerous regulations and incensed at the impositions of foreigners, believe vaquitas are already extinct. Others claim they’re a hoax. “Most people here,” one fisherman in the coastal town of San Felipe told me, “think they don’t exist.”

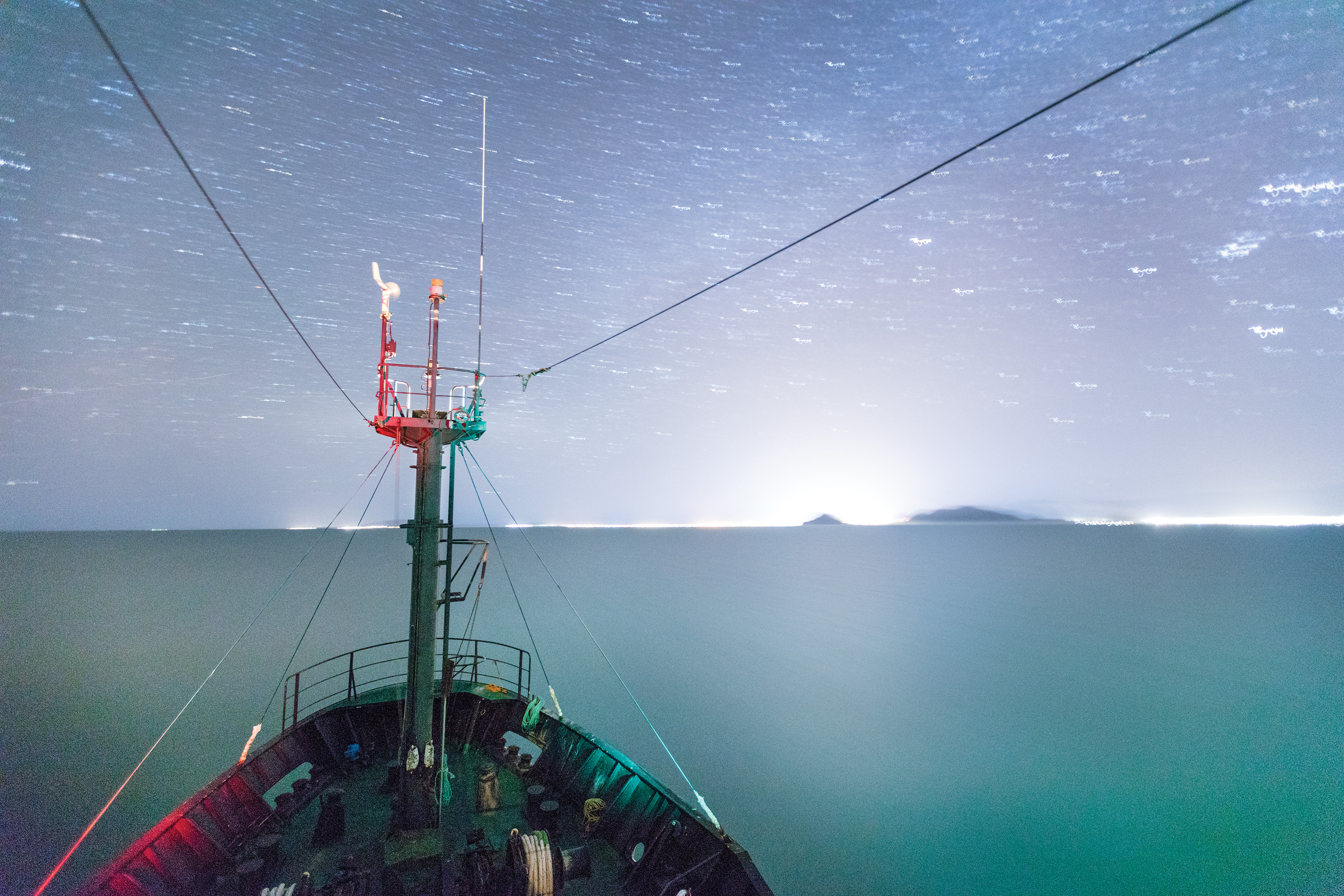

The Gulf of California, known also as the Sea of Cortez, seems, at first, an improbable place to search for a marine mammal. The long finger of the Baja Peninsula is desert, all blinding sand, sere scrub, and crimped purple mountains; the upper Gulf—the Alto Golfo—materializes like a mirage, a band of pale shimmering water beneath a faded-denim sky. The Gulf here, where the beleaguered Colorado River limps to the finish line after its tortuous journey through the American Southwest, looks more like a sump than a sea. In summer, it can approach bathtub temperatures. These are among the most fecund waters on Earth, churned by tides into a nourishing soup trafficked by creatures from fin whales to great white sharks. When John Steinbeck sailed the upper Gulf in 1940, he found it “almost solid with fish—swarming, hungry, frantic fish, incredible in their voraciousness.” Among those frantic fish are schools of coveted totoaba, which surge into the upper Gulf to spawn in late winter and early spring: the most profitable time of year to be a poacher, and the most dangerous to be a vaquita.

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

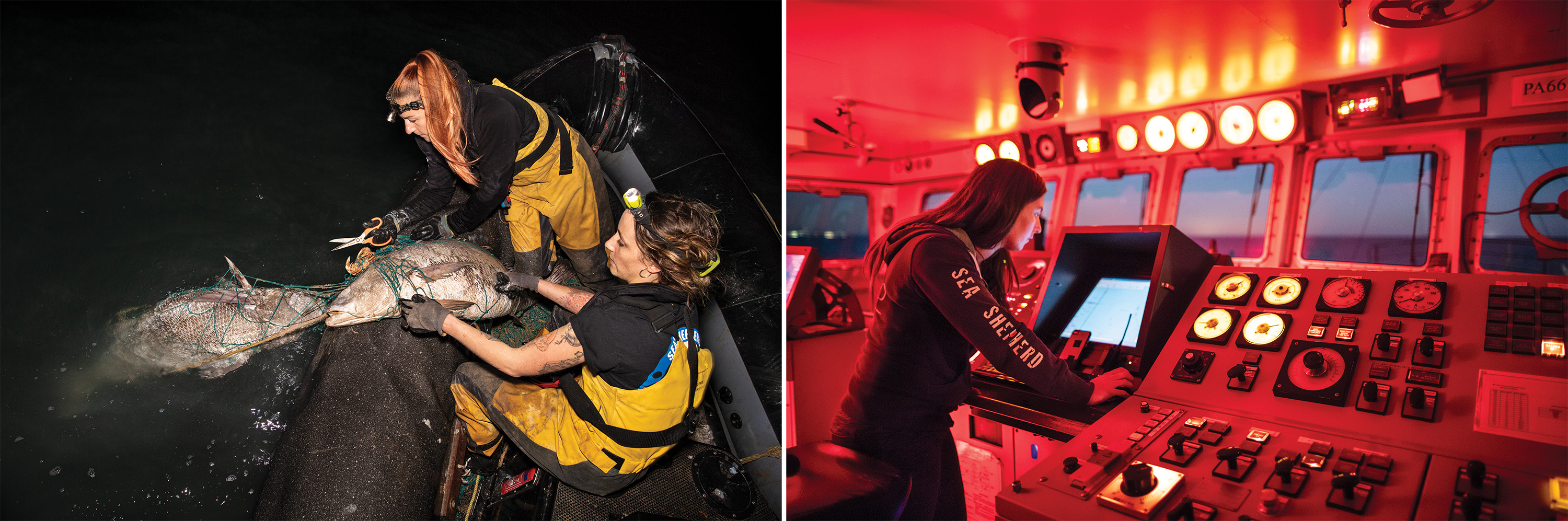

One March morning during the height of totoaba season, I climbed into a black inflatable raft at the San Felipe harbor, a dusty port cluttered with rusted shrimp trawlers and patrolled by pelicans. At the craft’s wheel stood Raffaella Tolicetti, an athletic Italian, dark-haired and earnest, with a seabird’s silhouette tattooed on her shoulder. Emblazoned on the raft’s front panel was a modified Jolly Roger, its grinning skull hovering above a crossed trident and Little Bo Peep crook. This was the piratical logo of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, the controversial band of nautical vigilantes who had come to Mexico to save a species beyond saving.

Tolicetti motored me out to Sea Shepherd’s 183-foot-long mothership, the SSS Sam Simon, anchored a half-mile offshore. Anti-Poaching was printed in towering letters on the hull. Gaping shark jaws had been painted on the bow, as though the Sam was preparing to engulf any lawbreaker that crossed its path. We scaled a rope ladder onto the deck, which bristled with cranes and radar towers and smelled of iron and fish. A shaggy Australian named Alistair Allan, erstwhile punk guitarist and current first mate, arrived to show me around the warren of cramped bunks, low-ceilinged hallways, and steep staircases belowdecks.

“People spend months on this ship,” he said. “We’re kind of a weird family.” The volunteer crew—quartermasters, engineers, welders—skewed young and European, their skin tattooed with creatures from every corner of the animal kingdom: penguins and wolves, snakes and squid, green squirrels and dancing boars. Allan’s own bicep was adorned with a vengeful-looking seal gripping a spiked club in its flippers, perched atop the word JUSTICE.

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

Sea Shepherd was founded in 1977 by an activist named Paul Watson, shortly after he was excommunicated by Greenpeace for his radical tactics. Under Watson’s leadership, Sea Shepherd emerged as a sort of extra-state maritime constabulary, hounding poachers and whalers across the high seas despite conspicuously lacking official enforcement powers. Sea Shepherd scuttled fishing boats and slashed enemy ships with a giant blade dubbed the Can Opener; after one of Watson’s vessels slammed into a Costa Rican boat and sprayed its crew with fire hoses, local officials charged Watson with attempted murder. (Those charges were later dropped, though Costa Rica maintains a warrant for Watson’s arrest, for shipwrecking.) The group waged its most famous fight against Japanese whalers in Antarctica, a battle immortalized by the reality show Whale Wars. During one memorable campaign, the Sam Simon—named for a creator of The Simpsons, who’d donated $2 million—was rammed by the Nisshin Maru, a massive factory whaling ship. When the vessels collided, Tolicetti recalled to me, the floor tilted and steel screeched, “as though we were a can of soda.” The Sam, I noticed, still bore the scars: dented railings, smashed deck lights.

The vaquita campaign—dubbed Operation Milagro—was different. No longer was the Sam Simon cruising the lawless high seas; the upper Gulf lies in Mexico’s national waters. There were no collisions or can openers. Instead, when the Sam and its sister ship, the Farley Mowat, stumbled upon poachers, they filmed them and alerted the Mexican Navy. The group passed the rest of its time peacefully dragging grappling hooks through the sea, snagging illegal nets. The pirate had become the police officer. When I visited the Sam Simon, no sooner had I boarded than the ship hooked a gillnet, which came up loaded with five totoabas, Doberman-sized fish with metallic scales and clouded eyes. “The nets, the illegal fishing—it never stops,” one crewman grumbled.

The excitement had just begun. That afternoon, the Sam‘s radar detected a panga, a small motorboat, about two miles out, squarely within a designated vaquita refuge. Allan lifted his binoculars to divine the boat’s intentions. “The giveaway is that there’s a large number of people on the bow,” he said. “That’s where they have to haul the net from. That’s telltale.” He set course toward the panga, then radioed the aft deck. It was time to fly.

I scrambled sternward and found the Sam Simon‘s resident pilot, a mohawked Irishman named Jack Hutton, hastily assembling a white drone. A burst of radio chatter authorized takeoff. The drone leapt aloft, its rotors buzzing like an angry wasp. Hutton paced the deck, guiding the machine from a joystick that hung around his neck. A Samsung tablet mounted to the controller showed us the feed from the drone’s camera, the sea rolling by at 40 knots. The crew gathered around, the air pregnant with chase.

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

“We have visual via the drone,” Hutton said. The drone swung over the panga, whose captain opened throttle. The drone pursued. I leaned over Hutton’s shoulder to watch the drama unfold on the screen. The drone hovered nearer the boat, which skipped along like a well-flung stone, casting a foamy V-shaped wake as it fled. It was a beautiful scene, as bright as a Mondrian canvas: the teal water, the white wake, the yellow slickers of four fishermen standing in the stern, eerily nonchalant. The drone’s eye zoomed in, and, with a shock, we saw a dozen totoabas lying like firewood on the panga’s floor. Sixty thousand dollars of contraband, on the low end, in a country where the per capita income averages $3,000 a year. I found that I’d forgotten to breathe.

“Dude,” one crewman murmured. “This is such a good shot.”

After a few minutes of cat-and-mouse, the drone neared the end of its battery life, and zoomed back to the Sam Simon. The crew was jubilant. “That’s one of the first times we’ve gotten footage of fish inside a panga,” Allan said. Photos were relayed to the navy. Any minute, we figured, the cavalry would arrive.

But the afternoon took a disheartening turn. The panga cruised into shallow water, where the deep-hulled Sam Simon couldn’t pursue. There it paused to pull another gillnet, and was soon joined by more pangas—four altogether, hauling illegal nets in broad daylight. Tolicetti bent over her phone, exchanging texts with a naval officer. “The guy keeps saying: ‘Please don’t lose them, please don’t lose them,'” she fretted. “I’m like, OK, but just come!”

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

They didn’t come. The sun sank behind the folded peaks of the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir; the stark day faded to dusk. In one report, I’d read that in the upper Gulf the navy had stationed a surveillance team whose arsenal included “a helicopter, Persuader and Maul marine patrol airplanes, six Defender rigid inflatable boats, two jet skis, four interceptors, three small boats, five pick-up trucks, and two Unimog vehicles.” That evening, though, it didn’t dispatch so much as a canoe. The pangas converged and broke away like dancers, fearlessly exchanging fish and nets. I wondered if the Sam Simon‘s crew missed the good old days of vigilantism.

Tolicetti and Allan ducked into the galley and returned with bowls brimming with pasta and beans—vegan, of course. Tolicetti’s phone pinged again. “Oh no,” she said. “Oh no. Holy cow.”

“What?” Allan demanded.

“They found vaquitas dead.”

“Vaquitas, plural?”

Tolicetti could only nod, her stricken face illuminated by the screen’s glow. The Sam Simon turned to shore.

In 2006, a young Mexican-born marine biologist named Catalina López Sagástegui arrived in the upper Gulf to help make sense of the vaquita mess. She was no stranger to clashes between fishing communities and marine mammals—she’d worked with gray whales and bottlenose dolphins further south along the Baja Peninsula—but she quickly realized that she’d stumbled into a far nastier fight. Fishermen and conservationists could barely sit at the same table without triggering a shouting match. Much of the animosity, she surmised, stemmed from the fact that the parade of non-profits had never fully acknowledged that fishermen were members of the ecosystem, as bound to the Gulf as the vaquita itself. “One of the first things fishermen told me when I got there,” López Sagástegui said, “was: ‘You don’t have to live here—you get to go home.'”

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

López Sagástegui and her colleagues made gradual inroads, convincing some fishermen to go to sea with trackers on their boats so that scientists could collect data about the industry. And then the illegal totoaba trade detonated. When López Sagástegui came to the upper Gulf, she told me, “I thought it was the worst situation in the world.” She laughed sadly. “Now when I look back on it, that was easy.”

A week before I arrived in the Gulf, years of building pressure found violent release. In a coastal town called Golfo de Santa Clara, dozens of fishermen attacked officials from Mexican environmental agencies. The fishermen were furious that they hadn’t been permitted to catch corvina, a slender relative of the totoaba that also spawns in the Gulf. The corvina fishery is among the region’s most lucrative industries, and, unlike totoaba gillnets, corvina nets are generally too fine to ensnare vaquitas. But the government feared that totoaberos could use the corvina fishery as cover, and delayed issuing permits. Denied their final reliable source of income, fishermen lashed out, beating three inspectors and burning government property. Newspapers showed boats and trucks smoldering in the sand.

Two powerful forces seemed to be feeding each other, like colliding fronts building into a thunderstorm. First, there was the justifiable anxiety afflicting the area’s fishermen. Not only had the corvina fishery been postponed, but the temporary gillnet ban was threatening to become permanent—even as a compensation program, which paid fishermen a monthly wage to offset their lost income, was nearing its end. (Several months later, the ban was made permanent and the compensation program extended.) Although the government had spent years developing vaquita-safe trawl nets, the new gear didn’t catch shrimp as well as the old, and scientific reports lamented that the net-research process was plagued by an “absence of coordination and oversight.”

Second, Mexico’s infamous drug cartels were reportedly tightening their grip on the totoaba game. Mexican investigative journalists noted that totoaba trafficking routes closely paralleled the Sinaloa Cartel’s. Rumor had it that a crime boss had been murdered over totoaba-trafficking competition. Although fish trafficking was finally criminalized in April of 2017, poachers are rarely prosecuted. One night in San Felipe, while eating dinner at La Vaquita, a few scientists and I watched two pick-up trucks tear down the street, pangas dragging from their trailer hitches, totoaba-gauge gillnets piled above the boats’ gunwales. Many minutes later, a police car meandered along the road, sirens off; when it reached a fork, it cruised off in the opposite direction that the pangas had taken. “No es posible,” one of my companions murmured with a sad smile.

Although San Felipe was more tranquil than Santa Clara, unease hung over the town. Fishermen who’d spoken out against poaching and corruption had received death threats. Now they refused to talk to me, even anonymously. A program that would pay 40 law-abiding fishermen to sweep the sea for illegal nets had been paused, for fear the government couldn’t protect its helpers from reprisal. Even Sea Shepherd seemed spooked. Oona Layolle, Operation Milagro’s French-born co-leader, told me that poachers had recently escaped arrest by firing off assault rifles, a frightening escalation. (Months later, on Christmas Eve, totoaberos would shoot down one of the group’s drones as it hovered overhead.) Soon after I left, fishermen demonstrated against Sea Shepherd’s interference, burning a panga in downtown San Felipe to protest the foreigners’ incursion.

Through the backlash ran a current of legitimate grievance. Several nights after my tour aboard the Sam Simon, I met two fishermen whose lives had been rearranged by vaquita recovery: spindly, white-mustached Victor Manuel Horozco and his husky, goateed colleague, Rafael Sánchez Gastélum. We rendezvoused on the Malecon, a seaside riviera that bustled with teenage bicyclists popping wheelies and vendors selling roasted corn and men playing tubas. A mural depicting a female vaquita and her calf swimming through a sunlit ocean adorned a nearby sanitation plant.

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

Gastélum did most of the talking. He’d been fishing for shrimp and finfish since he was 13, he told me, though these days he mostly took tourists sportfishing. Rather than raging against vaquita conservation, he’d accepted it. That was where the money was now, and recovering the porpoise seemed like the best way to revitalize his industry. He’d adopted vaquita-safe fishing gear, helped scientists monitor the dwindling population, and planned to assist the search for illegal nets. He received 8,000 pesos a month—around $400—as compensation for not fishing commercially. Sure, he’d seen vaquitas, though he wasn’t awed by them. “It’s just an animal,” he said, shrugging.

Although Gastélum was one of the fishing community’s most vocal spokesmen for saving the vaquita, he hardly seemed ecstatic about his new career in conservation. The monitoring payments barely covered his gas. The vaquita-safe trawls didn’t work nearly as well as the old gillnets. The monthly checks were peanuts, less than he’d sometimes made in a single day of fishing. The more pangas and permits you owned, he pointed out, the larger your compensation package. “The person who gets 200,000 pesos, he is happy at home, he doesn’t have to go fishing,” he said. Even well-meaning recompense simply served to enrich the powerful. “My whole family has to eat,” Gastélum added. He was working with scientists because he had no other choice. “If they allowed us to fish, I would be fishing.”

Horozco listened silently as his friend talked, leaning against the Malecon’s railing, the black mass of the Gulf to his back. When Gastélum at last wound down, he chimed in. The older man by a couple of decades, Horozco recalled a better time—a time not only before the whole vaquita mess, but when the Colorado River still reached the sea, before American dams and canals sucked it dry to water Las Vegas casinos and Imperial Valley crops. On the way down to San Felipe, I’d driven past La Salada: the river’s former delta, once a lush mesquite paradise, now a forbidding desert, bright and hard and featureless as a frozen lake. “People would fish with hand nets from the road,” Horozco said wistfully. “Now there’s no water and no shrimp.”

Unlike some locals, Horozco didn’t deny that totoaberos were responsible for the vaquita crisis. But he also wanted me to know that Mexico’s northern neighbor had been pillaging San Felipe’s water for decades. It was easy to blame totoaba poaching and conservation restrictions for destroying the town’s fishing industry, but truthfully its collapse had been unfolding since engineers in my own country drew up blueprints for the Hoover Dam. If the town’s marine economy crumbled once and for all, Horozco wasn’t sure what he’d do.

“This is a fishing town,” he said. “It has always been. I can’t become a miner or a construction worker. A job on the sea—I can do that.”

How do you track the demise of a species so elusive that locals debate its very existence? You don’t look; you listen. In 2011 a group of scientists, led by Armando Jaramillo-Legorreta, planted the Gulf with dozens of acoustic detection pods: narrow cylinders that record the vaquita’s vocalizations, rapid bursts of clicks that, slowed down, tick like the dial of a rusty combination lock. That first year, some of the pods picked up over a thousand clicks per day. By 2017, none registered more than a hundred. Every year the Gulf grows emptier, lonelier, quieter.

To a conservation biologist named Barbara Taylor, the creeping silence was eerily familiar. More than a decade earlier, in 2006, Taylor and other researchers surveyed China’s Yangtze River for the baiji, a freshwater dolphin endangered by dams, pollution, fishing, and shipping. If biologists could capture the final few baiji, the thinking went, they could relocate them to protected lakes. For two months, boats cruised the Yangtze with hydrophones, listening for the dolphin’s call. Factories lining the banks belched effluent into the river. The team called off the search each afternoon when the smog grew too soupy. Every day, Taylor grew more certain they’d arrived too late. Later that year, the baiji was declared extinct—the first cetacean exterminated by humans. Unlike Martha the passenger pigeon or Lonesome George the tortoise, the baiji’s endling never had a name.

Today, Taylor helms the scientific team monitoring the vaquita’s decline, which means that, for the second time in a dozen years, she is documenting the dire final days of a vanishing cetacean. She lives up a steep driveway in the San Diego hills, where, after my trip to Mexico, I visited her and her husband, a marine mammal biologist named Jay Barlow. I’d last spoken to her at a conference in Wisconsin the previous summer, at which she’d won a big award. Her once-obscure porpoise was finally generating headlines, but Taylor felt more like a hospice worker than an emergency room doctor. “I’ve been working on this for decades, and now I’m having a whole bunch of people show up and thank me for failing,” she told me over a mozzarella salad. A black vaquita decorated her white sweatshirt.

(Photo: The Voorhes)

Taylor is also a painter, an avocation that serves the dual roles of public relations and therapy. After lunch, we admired watercolors depicting bowhead whales, harbor porpoises, and, of course, vaquitas. She showed me her latest work-in-progress, which featured a flock of four vaquitas flying in formation behind a California condor—a giant vulture that had narrowly avoided extinction itself. She was considering adding another vaquita, this one hatching from a condor egg. “Would that be too cheesy?” she wondered, and laughed.

The condor was a carefully chosen symbol. Beginning in the 1990s, scientists saved the bird by capturing adults, breeding them, and reintroducing their offspring to the wild. In 2016, Taylor’s recovery team announced that it would try to rescue vaquitas in similar fashion. The proposal, dubbed Vaquita CPR, was undeniably desperate. Porpoises, skittish and easily stressed, are more difficult to catch and house than, say, bottlenose dolphins. Unknowns abounded: whether vaquitas could be husbanded in floating pens; whether they could be kept healthy and well-fed and libidinous. Sea Shepherd worried that precious porpoises would die in the process; other groups feared the Mexican government would use the program as an excuse for slacking off on enforcement. “It’s hard to feel good about putting animals in floating sea pens,” Taylor admitted to me. “But what would that vaquita’s life be like if it wasn’t swimming around in that sea pen? Odds are, it would be dead.”

In October of 2017, Vaquita CPR, endowed with a 67-person team, a $5 million budget, and a 135-foot-long repurposed Bering Sea crabber called the Maria Cleofas, launched operations. The project started auspiciously: The team managed to routinely locate the reclusive porpoises, including several mother-calf pairs. On October 18, the Maria Cleofas came upon a trio of vaquitas and successfully herded one, a juvenile, into a net strung behind a smaller capture boat. Veterinarians eased the calf into a transport box, dampened her dorsal fin with wet cloths, and boated her shoreward to El Nido, or the Nest, the circular mesh sea pen. But the calf didn’t take to her new environs, darting blindly around the pen, colliding with handlers, and floating at the surface, apparently exhausted. The crew, fearing for her health, rushed her back to the capture site and released her, hopefully to reunite with her mother. The failure concerned Vaquita CPR’s staff, but it didn’r defeat the project. Perhaps the group needed to try an adult.

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

Seventeen days later, at 4:18 p.m. on Sunday, November 4th, the opportunity arose. An adult female got her flippers and fluke snared in the capture net; the crew had her untangled and onboard within two minutes. At 4:26 she received an injection of a sedative called diazepam and three minutes later was transferred to another boat, the Defender, in a soft-sided sling. “She was really calm throughout that whole process,” Frances Gulland, the Marine Mammal Center senior scientist who helped oversee the capture, told me. “Her breathing rate and her heart rate were steady. We thought: ‘Oh, great, she’s going to be the older matriarch-type female. She’s going to be a great animal to start out with.'”

The ride to El Nido aboard the Defender took an hour. The sun set; the sky turned pink and then purple. At 6:42 p.m., the group slipped the porpoise into the net pen, and her tranquility evaporated.

“She swam really fast at the sides, and then right before hitting the net would do kind of a somersault, like an Olympic swimmer doing turns,” Gulland recalled. “She never slowed down. She actually accelerated. She was swimming faster and faster.” Scientists surrounded the pen, their faces furrowed with concern. At 6:57 she slowed down and floated like a log at the surface. Half an hour later she went limp. The team hurried her out of the pen and into the ocean, an emergency release. The vaquita raced away and then, to their horror, turned back, hastening toward the net pen, disoriented and frantic. She would have collided with the side of an adjacent boat if they hadn’t netted her again. This time her heartbeat was faint. She’d stopped breathing.

For nearly three hours desperate veterinarians ministered to the deteriorating animal. She was intubated, ventilated, and hooked up to intravenous fluids. The team massaged the cool, rubbery skin of her chest, felt the thump of her heart slow through her blubber layer and then speed up. Her blowhole gasped open, closed, open. At 10:10 p.m., she went into cardiac arrest. Eleven minutes later the team declared her dead. When Gulland necropsied her body that night, beneath fluorescent lights in a concrete-walled room at a facility called Camp Uno, she found the porpoise’s heart muscle had turned pale. She’d suffered capture myopathy, an extreme stress reaction. Her dorsal fin and tail, Gulland noticed, were notched with faded net scars.

In the episode’s aftermath, most media outlets portrayed it as the nail in the vaquita’s coffin: a “final bid,” a “last-ditch effort.” But a skeletal crew of vaquitas—a dozen, according to one watchdog group—still hung on in the Gulf, and they appeared to be breeding. If the tragedy had a silver lining, Taylor told me, it was that it had focused the world’s attention, more than ever, on the Gulf of California. The Mexican government had pledged, for the umpteenth time, to strengthen enforcement; maybe now they meant it. Perhaps, too, the surviving vaquitas had survived for a reason. “There’s a lot of natural selection going on here,” Taylor added. “The ones that are left, they’re not random. These animals recognized nets. They knew how to go around nets.” Conservation biologists are, by definition and necessity, a hopeful lot; concession was unthinkable, even if the game appeared over. Let down at every turn by humans, perhaps vaquitas would yet protect themselves.

In its 11th hour, the vaquita, like the baiji before it, has become a cause célèbre—elevated from anonymity just in time for us to remark on its likely passing. Meanwhile, the international spotlight still hasn’t shone upon legions of other obscure cetaceans, many dwindling by the day: Western Africa’s Atlantic humpback dolphin, Southeast Asia’s Irrawaddy dolphin, India’s Ganges River dolphin. These animals share a key trait: They inhabit the rivers and coastlines of developing countries where growing numbers of people derive their livelihoods from the water. Saving them will require tough laws, rigorous enforcement, and scientific research. But it will also require that conservationists help coastal communities develop economic opportunities that don’t jeopardize these species’ lives.

Over the years, ill-conceived attempts to diversify the Gulf’s economy have come and gone. Most bear the whiff of the tragicomic. In 2007, for instance, the Mexican government offered fishermen millions of dollars to turn in their gillnets and launch ecotourism businesses—which promptly collapsed when the great recession hit the following year. The most effective projects, the marine biologist Catalina López Sagástegui has come to believe, are the ones that begin from the bottom up: A single scientist penetrates a community, gains its trust, and labors for years to fit conservation solutions into its extant culture. The Gulf, she told me, had made fitful progress in that regard—evidenced, for instance, by fishermen agreeing to surrender their gillnets to try vaquita-safe gear. “We have the world looking at Mexico, and I think a lot of people will come out of this knowing a lot more.” For the vaquita itself, though, that hard-won knowledge has almost certainly coalesced too late: By the time you read these words, its endling may well be dead.

For now, the vaquita’s immediate future hinges on the valiant and imperfect efforts of well-intentioned vigilantes—foreigners working not with fishermen but against them. Two days after Sea Shepherd’s high-speed drone chase, the SSS Sam Simon deviated from its routine to search for a corpse. Raffaella Tolicetti had shown us photos, taken by locals, of two recent vaquita victims: an adult male, his black skin ragged and torn, and an infant, wrinkled from the womb. The calf had washed ashore, but the adult remained adrift. The carcass, if Sea Shepherd could recover it, had a morbid value, ironclad proof that the species persisted.

(Photo: Corey Arnold)

It was a glorious day, the sea flat as a billiard table. Marine life rioted around us: Dolphins frolicked in our wake, frigate birds flirted with the radar tower, fin whales crested to starboard. If vaquitas were this playful, I thought, they’d already be saved. The wariness that served them well in nature was also their downfall. Invisibility, in the realm of conservation, is death, no matter how cute you are. Whale-watching had saved the whales, but no ecotourism industry would bail out a creature so rare and retiring that its very existence was a matter of dispute.

We didn’t find the vaquita’s body that afternoon, though it would turn up days later, gnawed by fish and baked by the sun. Our search was curtailed by another crisis: The Farley Mowat had pulled a net containing a record 66 totoabas, and Sea Shepherd’s media gurus had to document the haul. The Farley carried the rotting fish ashore, where officials lined them up and knifed out their prized bladders. The dissection took hours. The smell was horrific. I wasn’t allowed to attend, but when I spoke with Sea Shepherd’s media director all he could talk about were the flies, the swarms that emerged to blacken the boats, the trucks, the nets, the dead fish baking on the concrete dock. The vrroooom of millions of tiny wings. “It was like a nightmare,” he said. They buried the whole foul mess in the desert.

A few days later I drove north up Highway 5, back to Los Estados. Uncountable legions of sphinx-moth caterpillars had hatched in the night, and their bodies, green and corpulent and unavoidable, inched across the pocked pavement, turning to jelly beneath my tires. As I passed through the sunbaked wastes of La Salada, the radio turned to static. Without auditory stimulus, my mind wandered, and I thought of something Oona Layolle told me. When Paul Watson, Sea Shepherd’s legendary Ahab, had first proposed a vaquita campaign, other captains had rejected it as hopeless. Only Layolle volunteered, her motives less messianic than journalistic. “Even if they disappear we can be there to document, record, and show the world that this cannot happen again,” she told me. If the vaquita blinked out, it would die as a media martyr, its expiration blogged and tweeted and filmed by drones. An endling for the Digital Age. Whether we’ll learn anything from its demise is up to us. Our track record does not inspire confidence.

This article was produced in collaboration with the Food & Environment Reporting Network, an independent non-profit news organization. All photographs are by Corey Arnold.

A version of this story originally appeared in the June/July 2018 issue of Pacific Standard. Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine. It was first published online on May 22nd, 2018, exclusively for PS Premium members.