This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Heading into the highlands of Tasmania, some 250 miles south of the Australian mainland, narrow black-topped roads meander through a wide river valley bounded by distant mountain bluffs. Two-track paths splinter off into grassy pastures, past skeletal trees bleached by sun and drought. All along the way, small signs dangle from wire fence lines: Danger Prohibited Area Poison. Little else would suggest that these fields represent the nucleus of the global opioid supply chain—the starting point for one of the world’s largest drug markets.

In Bothwell, a village where trucks packed with sheep idle outside a gas station, I met a farmer named Will Bignell. Bignell, a boyish guy in his thirties, with tousled hair and bright green eyes, was something of a reluctant seventh-generation farmer. He’d left his family’s farm in the midst of a prolonged drought, moved to Hobart, Tasmania’s capital city, and started a family. Then, in 2009, Bignell began making the hour-long commute up to the farm. Instead of raising livestock, Bignell plowed up pasture land and planted his first crop of opium poppies—a particular varietal, in fact, custom-tailored for pharmaceutical drug manufacturers.

He had a contract to grow these specialized poppies with Tasmanian Alkaloids, which, until it was sold in 2016, was the only agricultural research and development facility in Johnson & Johnson’s sprawling pharmaceutical empire. For a time, Tasmanian Alkaloids offered tens of thousands of dollars in cash incentives to farmers. Growers also reported receiving Mercedes-Benzes and BMWs for producing the highest yields of drug compounds. Across the island, Bignell saw how the potential long-term profits on investment had drawn young professionals away from desk jobs on the Australian mainland back to the island.

“If it was just bloody Merinos and fine wool, I doubt they’d come back.” With poppies, Bignell says, farmers could support a young family. “You get the bloody price reward. It’s every farmer’s dream.”

Once harvested, the dried poppy plants are processed into a crude extract, and this so-called “narcotic raw material” is flown to manufacturing facilities. The active compounds found in the poppy, known as opioid alkaloids, are turned into active pharmaceutical ingredients, which are then formulated into analgesic medications that are prescribed to treat pain; manufacturers utilize the same starting material to synthesize compounds that can be used to reverse opioid overdoses and treat addiction, such as naloxone and buprenorphine.

Tasmania quietly emerged as the world’s leading supplier of licit opioids, at least initially, because of a breakthrough in plant breeding. In 1994, chemists tweaked the opium poppy so that the plant produced higher yields of thebaine, a chemical precursor for making oxycodone. More importantly, this transformation enabled United States manufacturers to evade a long-standing regulatory cap. Historian William B. McAllister, author of Drug Diplomacy in the Twentieth Century, suggests that thebaine may be a case of “regulatory entrepreneurship,” where pharmaceutical companies attempt to figure out ways of getting around international drug controls to gain market share. Tasmanian Alkaloids, a pharmaceutical company based in Australia, followed by other firms, was able to ship thebaine despite the formal agreements because Drug Enforcement Administration rules governed the importation of morphine but, by 2000, clearly did not apply to thebaine. This regulatory regime was an unheralded but necessary precondition for the explosive growth of opioid production and oversupply in the last 25 years.

In a statement, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., says Johnson & Johnson previously owned two subsidiaries, Noramco, Inc., and Tasmanian Alkaloids, which were involved in producing the active ingredients found in opioid-based painkillers. “This manufacturing process is strictly regulated, limited, and monitored by the DEA and global authorities. They enforce regulations and set distribution quotas based on their assessment of the need for medicines containing these substances, and our businesses always complied with these rules.” In its statement, Janssen adds, “We no longer own these subsidiaries, and we do not promote any opioid pain medications in the United States.”

Because global drug policy overwhelmingly focuses on supply shocks to the illicit market—such as efforts to eradicate poppies and to punish people who produce illegal drugs—the licit side of the ledger receives disproportionately scant attention. But historically, Kathleen J. Frydl writes in The Drug Wars in America, 1940-1973, “one of the best ways to discipline the illicit market was to regulate the licit one,” that is, through deterrence policies that jeopardize a doctor’s or drugmaker’s access to the licit supply, and through criminal sanctions.

(Photo: Stephen Dupont/Contact Press Images)

In this case, international regulators and the DEA noticed Tasmanian suppliers were sidestepping the spirit of the original rules, but rather than closing the supply loophole, the DEA did what pharmaceutical lobbyists had been asking for and left the oxycodone pipeline wide open.

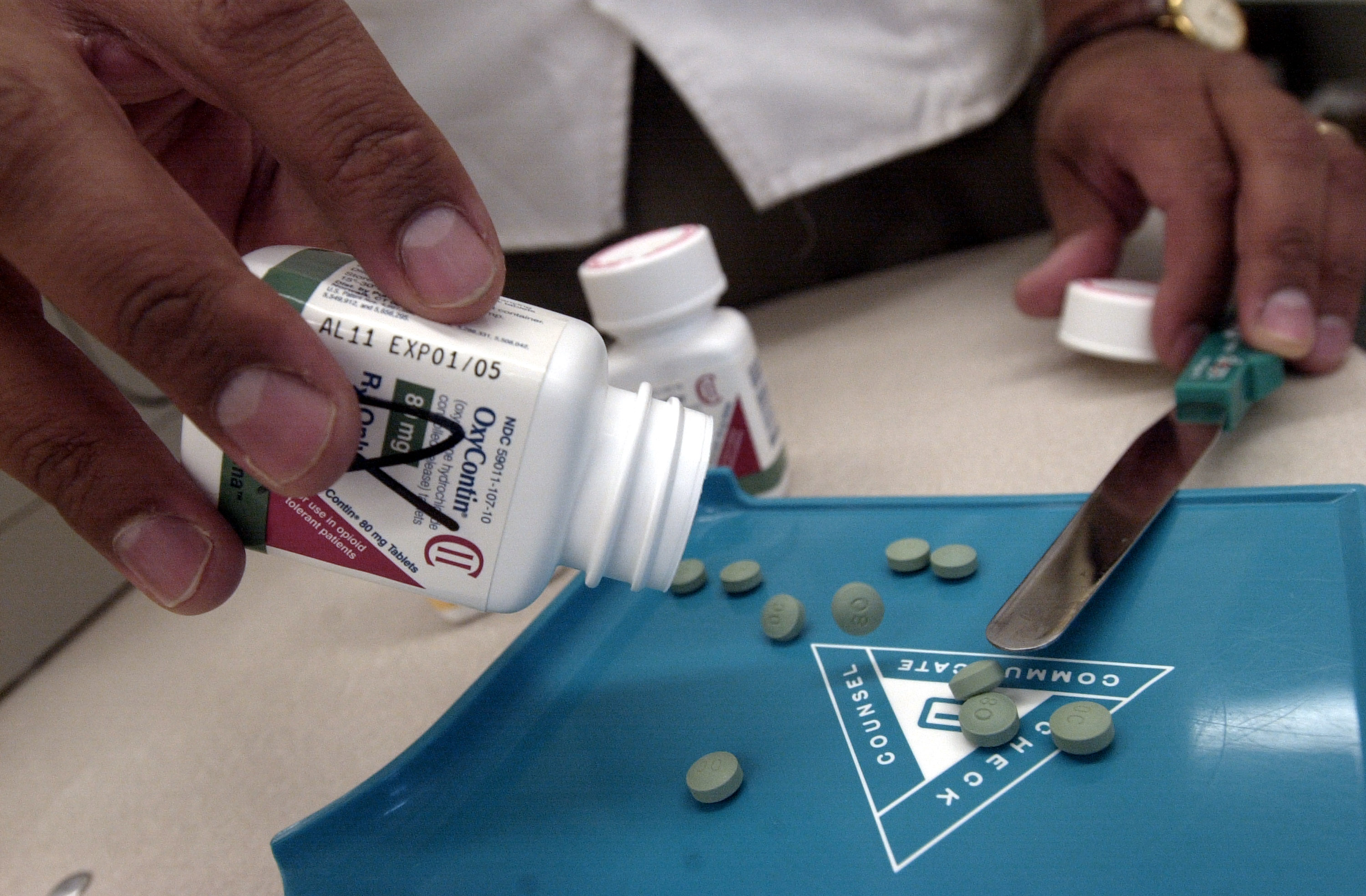

By 2011, J&J claimed in a report to Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration that Tasmanian Alkaloids’ high-thebaine poppy was providing 80 percent of the global market for oxycodone raw materials. Oxycodone, a chemical cousin of heroin, helped set the first wave of the overdose crisis in motion. Oxycodone made from Tasmanian-grown thebaine was formulated into brand-name OxyContin sold by Purdue Pharma. Today, some addiction specialists argue that a doubling-down on law enforcement and border security, combined with efforts to reduce prescriptions and to stem the diversion of legal pharmaceuticals, has left many people who use opioids at the whim of a changing market. Without a proportionate increase in evidence-based medications and treatment, experts such as Dan Ciccarone, a researcher at the University of California–San Francisco, warn that an approach that squeezes the licit balloon compels people who use opioids to turn to poisoned products, such as fentanyl and other synthetics contaminating the black-market heroin supply.

Stefano Berterame, an official at the secretariat to the International Narcotics Control Board, a quasi-judicial watchdog that tracks supply and demand, tells me that the U.S. policy on opioids permitted prescribing that “was not rational.” But the INCB requires governments to establish their own national estimates, and traditionally put its faith in the U.S. authorities, rubber-stamping the ballooning manufacturing quotas set by the DEA. “In the U.S., they have a good understanding of the national need,” Stefano says. “We are in no position to challenge the estimates produced by the U.S.”

How Tasmania Thwarted Regulation and Turned the Opioid Economy Upside Down

Tasmania’s ascendency in the global opioid market is often attributed to the island’s location: Its “remoteness, small population, and limited arable agricultural land,” as a 1989 report to the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs puts it, “enhances security and places a natural limit on expansion of opium cultivation.” But Brian Hartnett, a former executive at Tasmanian Alkaloids, says the real reason poppies grown for pharmaceutical production were marooned in the antipodes has everything to do with American actions.

“It’s really a reflection of U.S. government policy,” Hartnett says.

American farmers could grow opium poppies, but under the 1961 United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, and subsequent international drug control treaties, the U.S. agreed to continue outsourcing poppy cultivation primarily to what are known as “traditional suppliers,” which were initially defined as India, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Burma, Bulgaria, Iran, Pakistan, Vietnam, and the U.S.S.R. By the late 1970s, as state officials in Tasmania encouraged farmers to expand from experimental plots to broad-acre production, Australia, a non-traditional supplier, created a glut of narcotic raw materials that the U.N. Commission on Narcotic Drugs determined was, as the 1989 report later put it, “in excess of the world’s legitimate needs.” If U.S. drugmakers favored Tasmanian suppliers, then that would undermine U.S. treaty obligations, and so, in 1981, policymakers implemented what one Tasmanian Alkaloids executive referred to as the “infamous 80/20 rule.”

The 80/20 rule requires U.S. manufacturers to import 80 percent of all narcotic raw materials from India and Turkey, providing favored market access to these state-run monopolies. (The rule reinforces broader foreign policy objectives. It excludes other traditional poppy-growing regions, such as Afghanistan, from the licit marketplace for failing to curtail production of illicit drug crops.) Furthermore, the rule acts as a governor, or a cap, leaving just 20 percent of the U.S. market open to the seven multinationals exporting raw materials from industrial-scale operations in Australia, Hungary, Poland, France, and, until 2008, the former Yugoslavia (which has since been replaced by Spain)—that is, until Tasmania came along with the thebaine poppy.

Because morphine is difficult and expensive to convert into a class of drugs that includes oxycodone, the 80/20 rule effectively limited thebaine production, which, in turn, constrained production of these so-called semi-synthetic pharmaceutical painkillers. Then, in 1994, a Tasmanian Alkaloids researcher named Tony Fist dipped thousands of poppy seeds into a chemical solution and discovered a mutant poppy plant he called the “Norman” (a play on “no morphine”).

“It was a bit of luck, really,” Fist says. The mutant poppy produced thebaine instead of morphine, and, Fist says, it more than halved the costs of making oxycodone. Farmers planted the first commercial crop of Norman poppies in 1997, just as Purdue Pharma aggressively ramped up production of OxyContin, its patented oxycodone pill.

(Photo: Darren McCollester/Getty Images)

“If they didn’t get that thebaine,” Fist says, “they wouldn’t have been able to meet the demand for oxycodone.” The significance wasn’t lost on Tasmanian officials. Thebaine skirted the 80/20 rule, and, as one state official told Australia’s ABC radio, “there is no doubt whatsoever that demand for thebaine will increase, and the Americans particularly will take all we can provide.”

Which is exactly what happened: Between 1993 and 2015, the DEA’s annual aggregate production quotas—the total amount of opioids to be manufactured—increased threefold. (Over the same time period, Willem Scholten, a drug-control policy consultant in Lopik, in the Netherlands, estimates that the consumption of seven commonly prescribed strong Schedule II opioid analgesics—expressed in terms of morphine milligram equivalents—increased sevenfold.) The oxycodone production quota alone climbed from around 3.5 tons annually to over 150 tons. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 1999 and 2015, the average dose size per person nearly tripled.

The underlying causes of addiction are complex, and often result from repeated drug exposure. There are many social factors; some addiction specialists hypothesize that people self-medicate with opioids as a refuge from physical and psychological trauma, despair, and inequality. Patients prescribed opioids for long periods of time, and at high doses, run the risk of developing a physical dependence, and so, while the oversupply of opioids does not necessarily lead to addiction, dramatic shifts in supply made illicitly diverted pharmaceuticals, such as oxycodone, oxymorphone, and other painkillers, the drugs of choice in many communities.

By 2001, OxyContin, the poster pill of the crisis, had earned a reputation for being “hillbilly heroin.” In 2017, the pharmaceutical company Mallinckrodt agreed to pay $35 million to settle a Department of Justice lawsuit alleging that it had failed to meet its obligations to detect and to notify the DEA of suspiciously large orders of generic oxycodone. (Mallinckrodt denies the allegations, and the settlement contained no admission of wrongdoing.)

Back in 1999, a Tasmanian state official said in a broadcast interview that U.S. federal regulators considered closing off the loophole and extending the 20 percent cap to cover thebaine from Australia and other non-traditional suppliers.

“The DEA explored changing the 80/20 rule,” Christine A. Sannerud, a DEA scientific adviser (who has since left the agency), says, “and sent notification to the companies, and then we decided to leave [the rule] as-is.” Alongside broader decades-long shifts, such as the breakdown of trade barriers and a liberalization in pain management, the DEA had, under pressure from pharmaceutical interests, relinquished a traditional tool for regulating opioid supply.

“That decision stands in contradistinction to the whole legacy of narcotic regulation,” says Frydl, the drug-war historian. “For the DEA to make that decision is completely nonsensical in my eyes.” (In response to a records request, the DEA produced no documents relating to the decision to leave thebaine exempt, although, in a 2016 letter to a Canadian firm, the agency affirmed the U.S. treaty obligations to support traditional suppliers.) In fact, DEA officials argue its import quotas for thebaine were justified, based on legitimate need, and came in response to a shift in prescribing practice.

In the end, the deregulation of the licit market, and a booming black market for illicit opioids increasingly laced with fentanyl, had one thing in common: Both compromised public health in the quest for profit.

Then, in 2011, Dan Ciccarone, the UCSF researcher who studies opioid market dynamics and leads a long-running National Institutes of Health-funded study called Heroin in Transition, saw the effects firsthand. He had flown to Philadelphia to do some field work. He wasn’t looking for dope but quickly bumped into a man who was. The guy was furious because, as Ciccarone remembers it, his doctor had recently cut him off.

He immediately called his colleagues to say, “I’ve just made a discovery that’s going to blow your mind.”

Ciccarone’s team spoke to dozens of people who transitioned to heroin when they couldn’t find pills, particularly after OxyContin was reformulated in 2010, and became harder to crush and snort. Their study was ongoing in 2012, just as the first wave of overdose crisis, which traced to prescription painkillers, gave way to a second wave, where deaths due to heroin increased. Since then, the U.S. has entered a third wave, wherein fentanyl and illicitly manufactured opioids have tainted the heroin supply, driving the number of fatal overdoses in the U.S. to more than 70,000 in 2017. While people who use heroin experience a range of preferences, Ciccarone and his colleagues find that many do not deliberately choose fentanyl. Before its recent supply influx, he says, demand for fentanyl was practically non-existent.

With regard to the current fentanyl crisis, as Ciccarone put it recently, “supply matters more than demand.”

A Reckoning

In 2016, SK Capital Partners, a private-equity firm, purchased Noramco and Tasmanian Alkaloids, the former J&J subsidiaries involved in the opioid supply chain. That year, Aaron Davenport, a managing director at SK, said he saw Tasmania’s designer poppies as a crucial asset for continued growth in abuse-deterrent formulations and the international market. (The terms of the sale are confidential, but the firm was not named in a string of recent state lawsuits filed against companies involved in the opioid supply chain.)

In early 2019, the Oklahoma attorney general called J&J an opioid “kingpin” in court filings for his lawsuit accusing the company of creating a “public nuisance” by deceptively marketing pharmaceutical opioids. The trial, currently underway, is expected to last two months. J&J denies any wrongdoing. Lawyers representing the company argue that the public nuisance statute is being misused, and say that the company can neither be held liable for selling government-regulated products nor for manufacturing, selling, or marketing Food and Drug Administration-approved medications made by other companies using their narcotic raw materials. “Our actions in the marketing and promotion of these important prescription pain medications were appropriate and responsible,” Janssen Pharmaceuticals says in a prepared statement. “The allegations made against our company are baseless and unsubstantiated.” The argument is that drug manufacturers cannot be held liable because regulatory authorities abdicated their duties.

Meanwhile, the FDA continues to encourage manufacturers to develop abuse-deterrent formulations. Researchers suggest that the strategy of making prescription opioids harder to crush up and tamper with, while being sometimes effective, can come with paradoxical, and unwanted, results. The continued deference to market forces asks the public to trust that existing regulations and restrictions would solve the current crisis, as surely as OxyContin, and other long-acting painkillers, had proven addiction-proof, and as surely as the saturation of communities with pharmaceutical-grade opioids had provided pain relief without leading to tens of thousands of accidental deaths.

For decades, the licit supply has gone largely overlooked, like a secret hidden in plain sight. In policy circles, the conventional wisdom once held that counternarcotics strategies that focused on reducing drug supply mattered more than demand, but public-health experts contend that supply-side interventions often backfire; and today, when the leading experts in academic medicine address the opioid crisis, their emphasis is increasingly on demand controls, including treatment, prevention, and other health-care and harm-reduction strategies. As one prominent policy expert at Carnegie Mellon University wrote in a 2015 commentary (in the context of illicit cocaine supply): “One of the very few things the field believed it could say with confidence was that supply control efforts cannot meaningfully reduce the use of a drug whose markets were already well established.”

Despite a market exclusivity for licit opioids, and the blanket prohibition on heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl, these policies failed to curtail addiction and the widespread use of drugs. Yet politicians keep turning to supply-side solutions.

Beginning in 2015, for the first time in nearly two decades, DEA regulators decreased aggregate production quotas for several classes of opioid painkillers; the agency has also reduced the total volume of thebaine U.S. manufacturers are allowed to import. The 2018 SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act, the bipartisan opioid bill that was recently signed into law, mandates additional review of the DEA’s quota; the law also requires an “explanation of why the public health benefits of increasing the quota clearly outweigh the consequences of having an increased volume.” But, in an interview with Pharmacy Times, a former DEA official-turned-whistleblower predicted that reductions to the quota will lead to drug shortages, thereby cutting off legitimate pain patients.

Like many proposed responses to the overdose crisis, reducing the availability of prescription opioids might seem like a good idea. But it comes at a time when legacy pain patients are reportedly being denied access to medical care, and some doctors are refusing legitimate requests over fears of disciplinary reviews. Even if a cap on opioids, combined with state-level drug-monitoring programs, leads to a massive downturn in opioid availability, public-health experts worry that, without committing additional resources for medication-assisted treatment, suppressive strategies will worsen the overdose crisis. A 2018 study published by researchers at Stanford University suggests that such reductions could potentially save lives over the long term by reducing the number of people who become addicted, but that the reductions are currently on track to kill a lot more people in the next five years. Physicians argue that these policies punish the powerless and harm individuals who are pushed toward increasingly contaminated illicit drugs.

(Photo: Stephen Dupont/Contact Press Images)

Back in Bothwell, Tasmania, the rural village some 3,000 feet above sea level, nobody stayed connected with his customers on the other side of the world quite like Will Bignell did: He beamed a wireless signal off a nearby hillside and logged into online forums to chat with other hobby pilots. Bignell flew drones over his farm, and pored over aerial images at such high resolution that he could zoom in and see an individual tire tread—all in an attempt to coax higher yields of drug compounds out of his poppy crop.

Poppies had played a central role in Bignell’s decision to move back to the family farm, where he now lives and works full time. “Living the dream,” he tells me when I call in late 2017. Bignell was out plowing his fields that day. Over time, it dawned on him that his livelihood was being called into question. One day, he’d struck up a conversation with a friend in Florida whom he’d met online, who asked him, “You grow opium?”

“Yeah, grow a lot of it,” Bignell says. “One of the world’s biggest suppliers. We supply America with a fair chunk of it.”

“Whoa, I don’t know how I feel about that. You know my sister died of overdose three years ago.”

On our call, the line went quiet. Then, Bignell told me, “That shit makes you really sad when you hear that.” In the background, I could hear the whir of machinery. Bignell rode along at a steady pace, turning over soil for next year’s crop. He had his hands off the wheel, and rumbled forward on autopilot. ❖

Author: Peter Andrey Smith is a freelance reporter based in New York. His work has appeared in Outside, Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, and others.

Photographer: Stephen Dupont is a photographer based in Sydney, Australia. He has produced photo essays from dozens of countries, including Afghanistan, Angola, Burma, Burundi, Cambodia, India, Israel, Iraq, Rwanda, Somalia, and Zaire. He is the author of several books, including Steam: India’s Last Steam Trains and Fight, a visual anthology of traditional wrestling around the world.

Editor: Ted Scheinman

Researcher: Jack Denton

Picture Editor: Ian Hurley

Copy Editor: Leah Angstman

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.