Award-winning artist and illustrator Anita Kunz may be Canadian, but for over 30 years she has been creating illustrations and covers for America’s most iconic magazines that urge readers to visualize and reconsider social and political events in the United States. Among the over 2,000 illustrations she has produced since she began magazine work in 1980, Kunz has depicted then-First Lady Hillary Clinton as Joan of Arc for the New York Times Magazine (1993’s St. Hillary) and George W. Bush riding a horse into Iraq with blinders on for the October 13th, 2003, cover of The New Yorker (Bush was the one wearing the blinders). The piece that got the most response from viewers, Kunz says, was published in 2007: a cover for The New Yorker depicting three women—one a nun, one blond and wearing a bikini top, and one in a burka—sitting beside one another on a subway. Kunz says it sparked conversation about “how women—we—feel we have to present ourselves in different cultures.” She is currently working on an extension to that project—a series that revisits iconic paintings by Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso, Jean-Michel Basquiat, David Hockney, and others from the viewpoint of a modern, secular woman.

Memoir

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption

Lawyer Bryan Stevenson has quite the superhero origin story. His elderly grandfather was stabbed to death in the Philadelphia projects when he was 16; at 26 he graduated from Harvard University with a J.D. and a master’s in public policy; at 35, he started an organization devoted to representing poor and marginalized peoples in the legal system. But in his 2014 memoir, Just Mercy, he focuses primarily on the stories of those whose rights he’s spent his years defending. Stevenson profiles clients of his Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative, including Walter McMillian, wrongfully accused of murder, and Evan Miller, a 14-year-old originally sentenced to life without parole. Stevenson paints a grim portrait of the American legal system’s history of jumbling the facts when victims are poor or people of color, even while the book offers qualified hope, in cases that won against the odds.

Why

“I just don’t think that white people have any clue that they live in a completely different world, and that the justice system is profoundly unfair. Bryan Stevenson is just so absolutely profound in the way that he talked about how we can help. I think we all need to be aware that the playing field is not level and that we need to make things right.”

Television Show

Black Mirror

What if people walked around with implants recording every moment of their lives, or a violent social-media hashtag led to the actual death of a major public figure, or people were allowed to rate their interactions every time they see a friend? These are some of the not-so-unlikely dystopian near-futures that Black Mirror, a British anthology show of speculative fiction now available to American audiences on Netflix, imagines in each of its uncanny standalone storylines. The episode Kunz found most powerful and chilling is 2011’s “The National Anthem”—the series premiere—in which an anonymous criminal threatens to kill a royal princess if the British prime minister does not perform a humiliating sex act on live TV.

Why

“Black Mirror talks about a future, but it’s a not-too-distant future. It talks about how we’re dehumanized, and the way that we could conceivably be living [in the future]. I think that, especially now in this post-election period, the timing is right for us to have a collective look on how we treat others and what kind of future we want.”

Podcast

The New Yorker Radio Hour

Launched in 2015, The New Yorker Radio Hour merges some print-only standbys—each episode is hosted by the magazine’s editor, David Remnick, and features interviews and storytelling in the spirit of the magazine—but also offers some levity too. (A recent episode featured an interview with David Letterman.) The show’s producers have said that they look to broadcast stories that wouldn’t fit within the magazines pages or on its website—indeed, the first episode came out of a memo that writer Jill Lepore sent to her editor for a story that didn’t fit in the print magazine.

Why

“I work for The New Yorker, I read The New Yorker, I find the stories are always really topical and interesting. But the Radio Hour brings a whole new dimension to it because they’re actually interviewing the people. It’s a little more intimate, a little more spontaneous, and there’s a little bit more of a dimension to it because you’re actually listening to people.”

Novelist

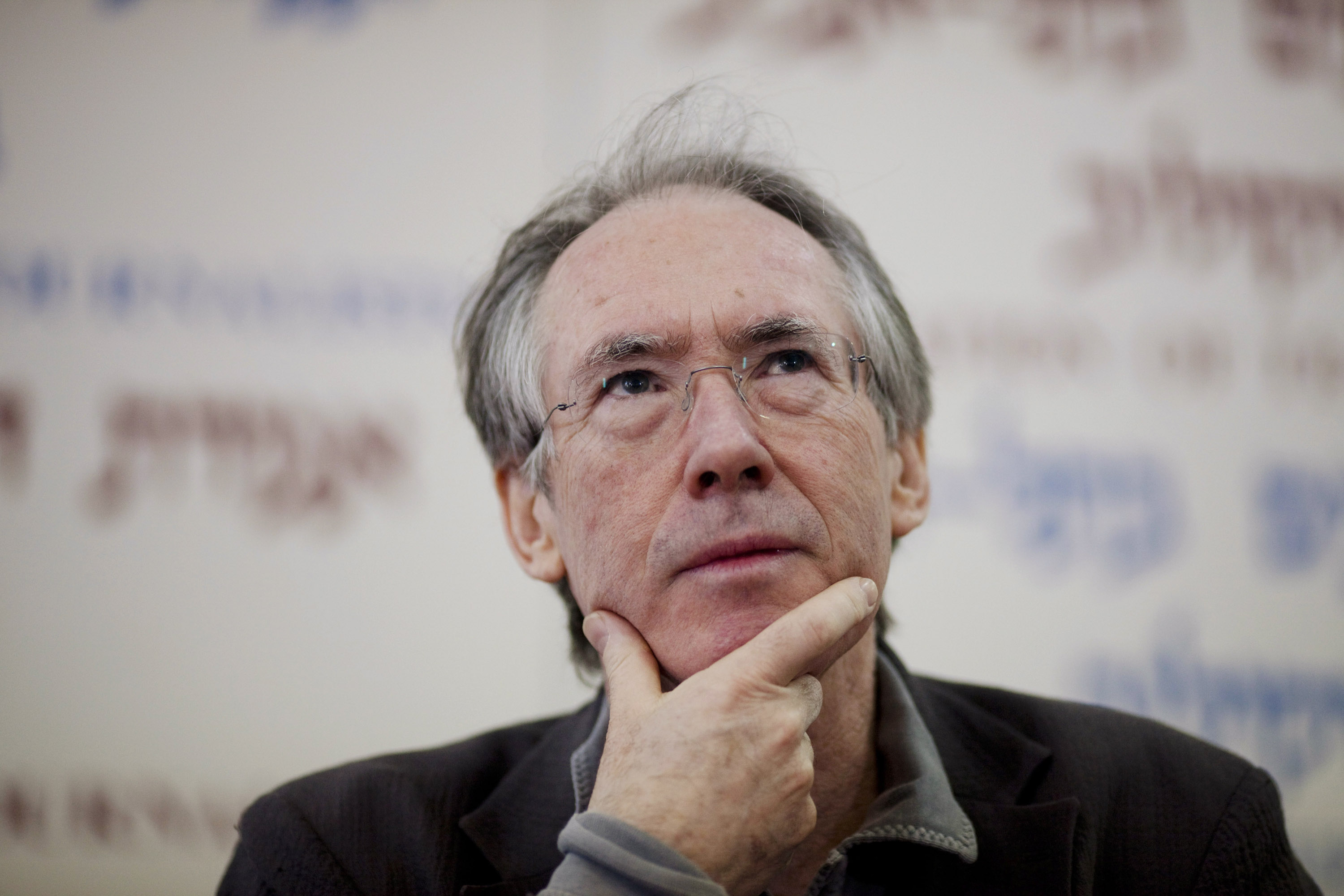

Ian McEwan

Though novelist Ian McEwan first made his name writing Gothic fables about incest, infanticide, and sadomasochism, in the last few decades his novels have veered toward realism, subsequently incorporating some sharp social and political commentary. While McEwan touched on the aftermath of 9/11 and climate change in 2005’s Saturday and 2010’s Solar, respectively, most recently he’s used a book release as a platform to discuss identity politics on college campuses. Following the release of last year’s Nutshell, McEwan told the Guardian, “What alarms me about politics on American campuses especially, but it’s spreading here, is that people are not addressing climate change or income distribution or poverty … they’re all caught up in tiny worlds of the self.”

Why

“There’s always these social concerns [in McEwan’s books]. There was one that had to do with somebody who had a stalker, there was one about climate change, there was one about unwanted children—they’re topical subjects that merit discussing, but he wraps a cloak of fiction around them. And he writes so beautifully.”

Naturalist

Sir David Attenborough

Years after TV host and naturalist Sir David Attenborough joined the BBC in 1952, he found an internal memo stating that he shouldn’t interview in front of the camera because his front teeth were too big. Lo and behold, 65 years later, Attenborough remains the channel’s iconic presence through his wildlife documentaries, having presented over 100 nature programs on the BBC and elsewhere—alongside all his writing, producing, and narrating credits. Renowned for his deep voice and passion for the natural world, in recent years Attenborough’s words (he writes his own scripts) have taken on an urgent tone. “I’ve been lucky in my lifetime to see some of the greatest spectacles that the natural world has to offer,” he says in an episode of 2000’s State of the Planet. “Surely we have a responsibility to leave for future generations a planet that is healthy, inhabitable by all species.”

Why

“I just love pretty much everything he does that relates to the natural world, because he gets so excited about everything. The way that we live—I live in the city—we’re just so out of touch with the natural world. But I think if we watch more shows like that, I think it puts us more in touch with the planet.”

Artist

Shea Hembrey

In 2007, recent art-school graduate Shea Hembrey went on a tour of every major recurring art exhibition in Europe he could get to, but was disappointed by what he found. The majority of the artwork he saw struck him as pretentious or ill-conceived or both. The result of his discontent is Seek, a biennial showcasing 400 works by diverse, undiscovered, and anti-establishment “artists”—all imagined and executed by Hembrey himself.

Why

“I’ve had some experience in the fine-art world, and it’s not always a welcoming place, especially for women—there’s a lot of elitism around it. [Seek] is a little bit like satire, because he talks about these different characters in a type of art-speak that you know if you’re in any way involved with the art world; It can be alternately profoundly brilliant or ridiculous-sounding. The whole thing becomes an art piece about the art world. It’s really, really funny and really smart.”

Illustrator

Jillian Tamaki

Canadian illustrator and comics artist Jillian Tamaki is perhaps best known for the graphic novels she’s created with her cousin Mariko Tamaki, including 2008’s Skim and 2014’s This One Summer, the first graphic novel to receive a Caldecott Honor. More recently she’s gained some solo attention for her Tumblr webcomic SuperMutant Magic Academy, “a satirical melange of X-Men, Harry Potter and teen dramas like Degrassi,” in the words of the Guardian‘s Chris Randle.

Why

“It’s kind of a new world to me, the world of graphic novels, because I’ve always been an illustrator. But I was invited to judge an award for the big graphic-novel and comics community in Toronto [the Doug Wright Award], so I got to read a lot of these books and they’re just astonishing—so authentic and very personal. I do one-off images or sometimes series, but these are really well-told stories. And because the pictures are there as well, it’s just an incredible way for these artists to communicate.”

Film Producer

Annie Koyama

After being diagnosed with terminal brain aneurysms and subsequently recovering from a risky operation to remove one, film producer Annie Koyama decided it was time for a life change—and time, finally, to offer material support to the people producing the zines and comics she loves. Using money she had made playing the stock market while on bed rest, Koyama founded Koyama Press, a small, Canada-based press dedicated to promoting and supporting both established and emerging artists. Since then, Koyama has published Steve Wolfhard’s Cat Rackham, Jane Mai’s Sunday in the Park With Boys, and Cathy G. Johnson’s Gorgeous, among others.

Why

“She just publishes all of these amazing young artists. I don’t know how easy it is to be published these days, but I imagine it’s not that easy, [because] everything she does is altruistic. She’s one of the best-loved people I know, and it’s because everything she does is for her young artists. She’s amazing.”

Film

The Piano

Set in 19th-century New Zealand, Jane Campion’s film about a mute mother coming to terms with life in an arranged marriage was a surprise hit when it debuted in 1993. Made for a slim $7 million, the film became New Zealand’s most successful international film ever, grossing $40 million at the domestic box office. The Piano also landed Campion, one of international cinema’s most respected female writer-directors, her first and only Academy Award, for screenwriting.

Why

“It’s really hard to think of a favorite movie. I have so many of them—but there was something about that movie. The quality of the filmmaking was really haunting. I love really great storytelling, but because I’m so visual, it’s such an added treat when [a film] is just as profoundly beautiful as this.”

Book

Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking

Rosa Parks, Audrey Hepburn, J.K. Rowling, and Gandhi are among the historic figures who news outlets have called introverts—yet, in her 2012 book Quiet, Susan Cain argues that Western institutions still (mistakenly) treat introversion as “a second-class personality trait, somewhere between a disappointment and a pathology.” The book, which remained on the New York Times top-15 best-seller list for 16 weeks after publication, has since been credited with persuading schools to re-examine admission policies and start clubs for introverts, and has been named as the inspiration for new office furniture lines by Steelcase and Herman Miller that emphasize creating “quiet spaces” for workers.

Why

“As an artist, the one thing we all have to do is promote, promote, promote. And I’ve always had a real hard time with that. I just think that, a lot of times, people who are louder, maybe in meetings or by virtue of their own personality, are taken at their word. People are maybe respected more, people are believed more, when, actually, there’s a lot of power in what introverts are thinking, even though they—we—don’t speak up as much. I think the book is all about treating with respect people’s viewpoints who are maybe not as loud and boisterous as other people.”