Two days before the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump stepped out of his personal jet and into a hangar at the Minneapolis-St. Paul airport to promise a crowd of more than 9,000 supporters that, if elected, he would halt arrivals of Somali refugees. Minnesota has the largest Somali population in America—estimated to be around 46,000—as well as comparatively large populations of Ethiopians, Liberians, and Nigerians. “You’ve suffered enough in Minnesota,” Trump told the audience, referring to Somali immigrants as a “disaster.”

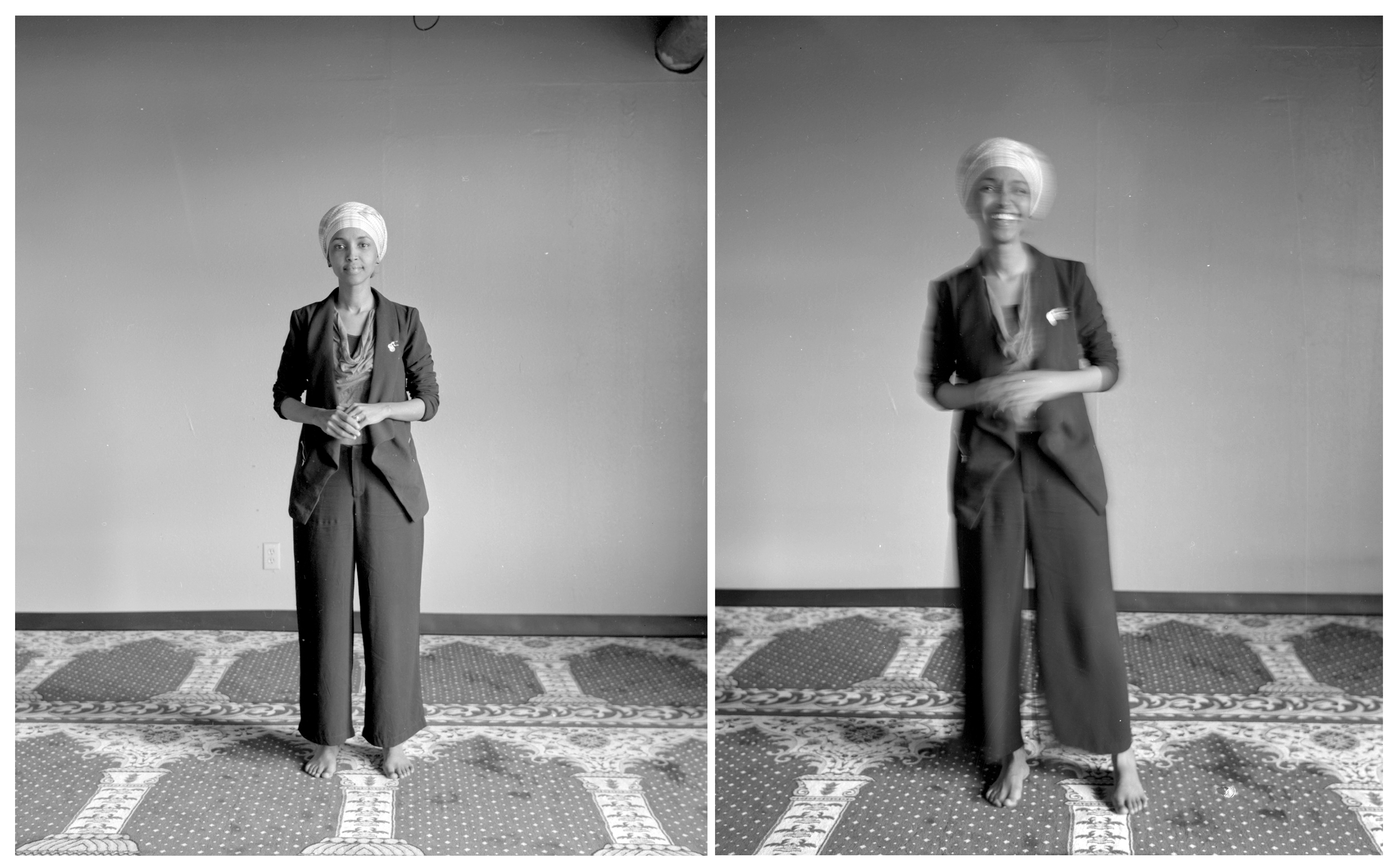

(Photo: Olivia Arthur/Magnum Photos)

Two days later, on November 8th, a majority-white district in Minneapolis elected Ilhan Omar to the Minnesota House of Representatives, making her the country’s first Somali-American legislator. Omar’s win—in a district that includes both a portion of University of Minnesota and an immigrant neighborhood known as Little Mogadishu—represented a clear rejection of Trump’s rhetoric. And even while the incoming administration planned to reverse years of progressive policymaking, the rise of an optimistic immigrant politician served as a reminder that our country’s unique promise to newcomers was still alive.

At Omar’s election-night celebration, her husband, Ahmed Hirsi, saluted the diversity of Omar’s campaign. “Look around,” Hirsi said, waving his arms to the corners of a ballroom filled with hijab-wearing Millennials and balding brown and white heads. “This is what this country’s all about. This is America. Folks from different backgrounds, different faiths, different cultures, coming together for one good cause. So, for those who believe that Somalis are a disaster, I say you are delusional. That is not, let me tell you, that is not what this country is about.” Wearing an ivory hijab pinned with a glittering brooch, the 34-year-old Omar beamed from the front row, one of her three children perched on her lap.

But the political moment still stung. The day after her election party, she released a statement of “mixed emotions” on her website: “There is a part of me that wants to go inside my house, close the curtains and lock the door, so I can keep my family safe.” According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, anti-Muslim hate groups rose from 34 in 2015 to 101 last year, and Omar understood that her heightened profile wouldn’t protect her from fomenting prejudice.

A few weeks later, after visiting the White House for a roundtable on progressive middle-class economics, Omar offered to help a D.C. taxicab driver with directions. The driver told her to shut up, cursed at her and her sister, ordered them to exit the cab, called them “ISIS,” and threatened to remove their hijabs as they got out. “Everything that happens to me doesn’t really happen to me, it happens to the community I live in, to the community I represent, to the identities that I represent,” Omar says. “The way that I deal with things—that also sets parameters and examples for people who will come after me.” That night, as she and her sister rushed to gather their belongings from the cab, Omar still handed the driver her credit card to pay.

(Photo: Olivia Arthur/Magnum Photos)

Back in July, a few weeks before Omar toppled 44-year incumbent Phyllis Kahn in the Democratic primary, Kahn told a reporter that “young, liberal, white guilt-trip people” were buoying Omar. But viewing her appeal as a triumph for her identities alone ignores both her broad coalition of support and her fiercely progressive agenda. As a former board member for the non-profit Legal Rights Center, she is quick to acknowledge that institutional racism sits at the root of the school-to-prison pipeline, and she has backed a bill that would require police officers to receive training in conflict mediation and cultural diversity. She hopes to help the University of Minnesota divest from fossil fuels; she was one of the first supporters of the Minneapolis bill backing a $15 minimum wage; and she’s a co-author of the Working Parents Act, a legislative package that would, among other things, guarantee workers access to paid sick and family leave. “There are a lot of reasons to look at her and say, yeah, she is emblematic of the Trump administration. She’s a response to it—the opposite of it,” says Minneapolis city councilmember Andrew Johnson, who gave Omar her first political job as his campaign manager.

Omar was born in Mogadishu, Somalia’s coastal capital, where she lived in a house filled with history books and African art. Her mother, who was Somali-Yemeni, died when she was young, and she grew up the youngest of seven siblings. Many of her family members were educators, and every morning before school, her paternal grandfather would call her into his room to remind her that she carried the legacy of Araweelo, a mythologized Somali queen celebrated for championing the rights of women and the oppressed. “I was made to believe that I had a role in making sure that everybody had their fair share,” Omar says. “I always really was that annoying child in the schoolyard trying to make sure that the little kid who was getting bullied stood up for himself and didn’t walk away crying.”

In 1991, after dictator Siad Barre was ousted, Somalia devolved into clan violence and civil war. Omar was only eight when her family made the decision to flee, after armed men tried to break into their house. The family split up to escape, and Omar ended up riding in a small plane previously used for transporting lobster. After four years in a Kenyan refugee camp, she arrived in America for middle school, where she learned English in three months. When Omar speaks of this journey—similar to so many of Minneapolis’ Somali immigrants’ journeys—her words smear into silence. “My voice has really been the only thing that is powerful about me, so to not be able to have that is debilitating,” she says, remembering the alienation she felt as a refugee who didn’t speak English.

Omar’s first exposure to local politics came when she was a young teenager, helping her maternal grandfather with cultural and linguistic translation at a Minneapolis Democratic-Farmer-Labor party caucus. After getting degrees in political science and international studies from North Dakota State University and returning to Minneapolis, she worked as a nutrition educator, served on the boards of local non-profits, and continued volunteering with DFL. Around this time, a Somali immigrant named Habon Abdulle—a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Sussex—began researching how Somali women in Minneapolis and London participate in politics, and she found something that surprised her. Though Minneapolis had a large number of women engaged as behind-the-scenes volunteers and campaign managers, they weren’t aiming for leadership roles. “They were never told, ‘You are good, you should run for office,'” Abdulle says. In early 2012, she invited a group of these women to start meeting monthly. Omar quickly stood out for her commitment to political activism. “In the process of us trying to encourage each other, I kind of was being molded by them into a candidate,” Omar says.

(Photo: Olivia Arthur/Magnum Photos)

She possesses an unabashed frankness that endeared her to voters. A week before the November election, she admitted in an interview that she broke down crying when first asking for political donations and told the audience at a Minneapolis improv show that she had to be asked 14 times before agreeing to run for office. When an audience member asked her to name two or three Minnesotans she most admired, she paused for a moment before listing Governor Mark Dayton, Prince, and Jessica Lange, explaining that Tootsie was one of the first movies she saw in America.

Her honesty and easy charisma helped rally a wide coalition of support in the first several months of the new administration. The day after Trump released an executive order that banned travel from a list of majority-Muslim countries, Omar scheduled an impromptu Facebook event for a gathering at her district headquarters. After laying down for a nap, she woke up to calls from the police department asking how she would handle the crowds. Thousands had already responded. She moved the Sunday event to a nearby recreation center, where it drew more than 2,000 people, many of them immigrants and refugees. Outside the community center, an overflow crowd of mostly white Minnesotans chanted “United States, united people.”

(Photo: Peter Van Agtmael/Magnum Photos)

“I want the agitators to be here,” Omar told me later, “and I want those that want to engage in the conversation to be here.” Omar believes resistance lies in civic engagement, and she stresses that community gatherings are a time for “co-governing.” In March, she hosted an Immigration Resource Fair in the same center, where—with the help of Somali, Oromo, and Spanish interpreters—approximately 40 families received pro bono legal advice. Her next goal is passing a sanctuary-state bill, which would, among other provisions, stop local law enforcement from inquiring about immigration status. Though the bill won’t be considered until 2018, it has already gained bipartisan support in the Republican-dominated Minnesota House.

While Trump continues to make headlines for his giddy exclusionism, Omar preaches inclusivity—even going as far as inviting him to spend a day with her in Minneapolis. “I hope he takes me up on my offer,” she said, reminding a packed room at the Minnesota capital in January that Trump’s great-grandparents were immigrants too.

She has filed a report with both the D.C. Office of Human Rights and the Department of For-Hire Vehicles about the taxicab incident, but she’s lost track of the progress. She would rather put her energy toward more important goals. “The path to equality is bumpy,” Omar says. “I think we need to be patient and resilient and realize that what we do today—if we’re not successful—it allows the second-generation to pick up the baton and run with it.”