Aside from the students, there isn’t much to suggest that this might be a classroom. It certainly doesn’t look like one. Instead of in rows of desks, students sit at tables, on couches, or along padded benches that look like they came straight out of a restaurant. There are treadmills in a corner. It’s quiet reading time, and a girl with crayon-colored hair pulls out a large blue book with Alcoholics Anonymous written in gold on the spine.

This is Independence Academy in Brockton, Massachusetts, one of around 40 recovery high schools in the United States. Across the hall from the main classroom, another student is strumming a guitar. He says “I.A.” is different than traditional schools, but that he likes it. “You have counselors that know about recovery, and there’s always someone to talk to,” he says.

As defined by the Association of Recovery Schools, member programs must have a primary purpose of educating students who are trying to recover from substance use or co-occurring disorders like depression or anxiety. Because recovery schools are all run independently of one another, they vary greatly in almost every other way: size, structure, curriculum, funding sources. Schools range between five and 100 students. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all approach,” says leading researcher on recovery high schools Andy Finch, an associate professor at Vanderbilt University and co-founder of the ARS.

Though rates of drug use among American adolescents have generally remained steady at two-decade lows, a 2017 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that overdose deaths among 15- to 19-year-olds spiked more than 19 percent between 2014 and 2015. Despite this, treatment options for young people who need them are often limited or inaccessible, and research shows that only about 10 percent of adolescents who need treatment actually receive it.

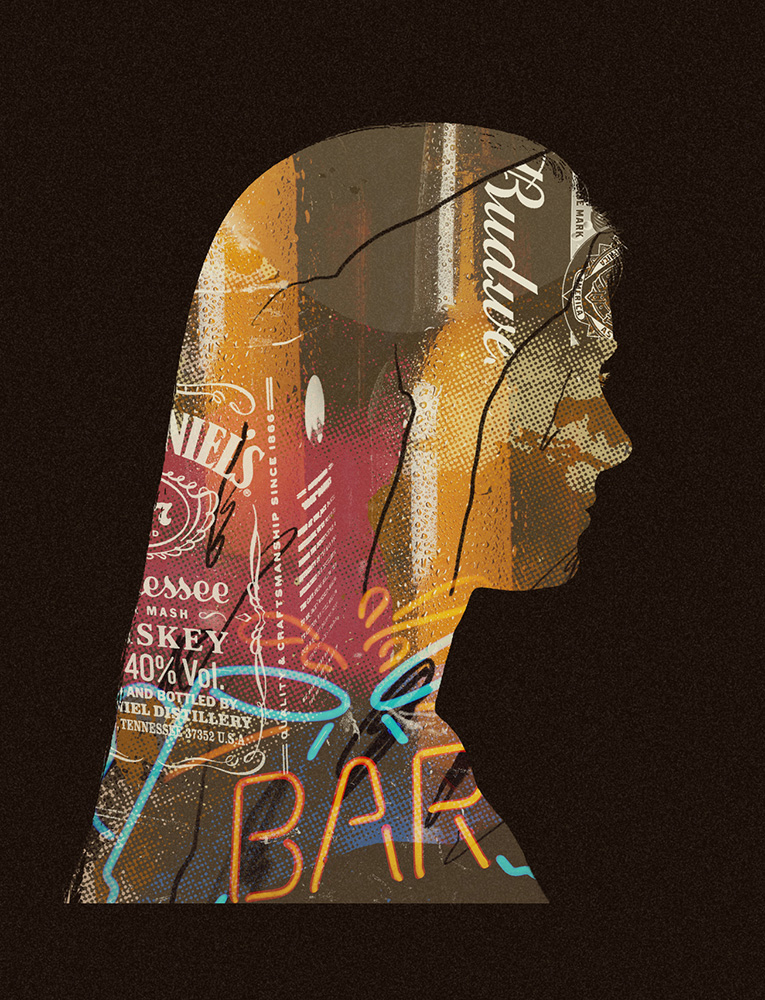

(Photo: William Widmer)

In the rare event that they are able to get treatment, students who are sent back to a traditional school environment after rehab—back to the same peer group and atmosphere that led to their struggles in the first place—are at risk of repeated failure. Such was the case for Michael Robinson, 18, who recently graduated from University High School, a recovery school in Austin, Texas. Robinson spent 10 weeks at an inpatient facility receiving treatment for depression and anxiety, as well as alcohol and drug use. “When he came out, he asked if he could return to his old school,” his mother says. “It wasn’t a good place for him to go back to. Going back to his [public] high school resulted in him starting to use drugs again. It got serious, and he was using on campus.”

Robinson began using Xanax and alcohol when he was 15, and bounced in and out of treatment before enrolling at University High School. “I had never heard of anything like [UHS], so I was sketched out by the whole idea. It was new territory for me,” he says. “I only had a couple weeks [sober when I enrolled]. I was like, ‘Screw this, I don’t want to be here.'” But Robinson says it’s been “fantastic,” and when we spoke in June, he had been sober 15 months.

While Robinson is just one example, all available research points to the fact that students who attend recovery high schools have better outcomes than those who attend treatment and return to their old schools. According to a 2014 interview with Finch, within six months of completing a recovery school curriculum, students have a relapse rate of only 30 percent, versus a 70 percent relapse rate for students receiving a more traditional intervention.

Much of that research has been done by Finch and his colleagues at the Recovery High Schools project at Vanderbilt. Their most recent study, published in the American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse this past summer, compared students who attended recovery high schools following substance use treatment to students who did not. The study followed approximately 200 students and included follow-ups at three months, six months, and 12 months. So far, the six-month outcomes show that students who were attending recovery high schools were nearly twice as likely to report complete abstinence—59 percent versus 30 percent. In addition, recovery high school students reported significantly less absenteeism than did their counterparts at traditional high schools.

In spite of the evidence that they work, recovery schools face a big challenge for funding. Because there’s no federal support for the programs, money often comes from multiple sources in a piecemeal fashion, creating a unique financial landscape for each institution. In Indiana, Hope Academy is the one of the few recovery high schools in the country that’s affiliated with an addiction treatment center. In Texas, UHS is funded through the University of Texas–Austin, along with a combination of program fees, grants from the community and private foundations, and individual donations. Independence Academy receives money from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, as well as the school districts that the students are referred from. The diversity in funding gives rise to incredibly different programs, but the schools share some similarities: Generally, they offer regular urinalysis screenings, for instance, and work on a case-by-case basis with students to provide individualized recovery support.

One factor that has so far proven essential to the long-term success of recovery high schools is the support of local legislators. In Massachusetts, where Independence Academy is based, Representative Jim Cantwell has been a fierce advocate. “Being a legislator, it was parents coming to me and saying, ‘We need help,’ or students would say they were going to treatment but it wasn’t serving their needs because they were back into an environment where the temptation was too great,” he says. The support of local officials has allowed Independence Academy to grow in the way that it has—referrals tripled over the course of the 2016–17 school year. William Carpenter, then a member of the Brockton School Committee (and now the town’s mayor), pushed to get the recovery school opened in his community after witnessing how his own son struggled with substance use when he was in high school.

Even if they can secure political support and funding, though, the schools face other issues as well, one of the biggest being a lack of transportation for students. Despite their success, these programs are still few and far between, and, in most places, transportation falls on the families. In Massachusetts, Independence Academy is the only recovery school in the southeast part of the state. There is a sizeable community of students who could use the services of the school but can’t manage to get there. The principal, Ryan Morgan, tries to help out with what he calls “creative solutions,” but there are large swaths of the state that he just can’t reach. “There are two bills, a House bill and a Senate bill, right now that would address the transportation issue. It would require districts to pay for transportation, but then they would be reimbursed by the state,” Morgan told me in 2017. “It would be a huge win for us.”

There’s also the larger issue of who has access to these schools. Young people of color are much more likely to face arrest and punishment from the legal system than their white counterparts, despite the fact that, according to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, black Americans use drugs at approximately the same rate as whites. Combine this with the fact that drug use and incarceration are linked—data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that many crimes are committed while under the influence of drugs or to get money for drugs—and recovery schools begin to seem like productive alternatives to incarceration for young people arrested for drug-related offenses. But as it stands, recovery high schools are overwhelmingly white. In its 2016 biennial report, State of Recovery High Schools, the ARS notes, “for the most part, recovery high schools have continued to enroll predominantly white and higher income students.” Independence Academy’s home of Brockton is a predominantly non-white town, but the vast majority of its students are white—for instance, in December of 2017, 27 of its 33 students were white. Many of the students who need them most are not currently able to find their way to recovery schools.

Some of these issues may come down to a lack of awareness. People simply don’t know that recovery schools are even an option available to them. Despite being open since 2006, Hope Academy is “the best kept secret in the city,” says Rachelle Gardner, the school’s chief operating officer. “I was at a forum in D.C. recently and these parents who have lost their children were asking why there aren’t more [recovery schools],” Gardner says. “It’s a good question; there should be. Every community should demand to have one. Unfortunately, it’s taking all these kids dying from opiates for it to happen.”

“They need [a recovery school]. For them, it’s life or death,” says Laura Losi, a teacher at Independence Academy. “We can spend money now or pay for coffins or jail later. Those are the alternatives.” Many who are against carceral solutions for the addiction crisis advocate for recovery schools as an alternative to jail, especially for young people. Cantwell says that, during his time as a district attorney, he saw that the majority of delinquent behavior was a result of substance use. “If you have these kinds of programs, these kids go to a recovery high school and they are not labeled juvenile delinquents; they have an illness,” he says.

As I’m packing up to leave Independence Academy for the day, the guidance counselor calls Morgan over. She shows him a text message she has just received from a former student, sharing the news that the student has just been accepted to the University of Massachusetts. “I never could have done it without y’all’s support,” the message reads.

Morgan looks up from the phone with a smile. “What a great way to go into the weekend.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of Pacific Standard. Subscribe now and get eight issues/year or purchase a single copy of the magazine. It was first published online on April 24th, 2018, exclusively for PS Premium members.