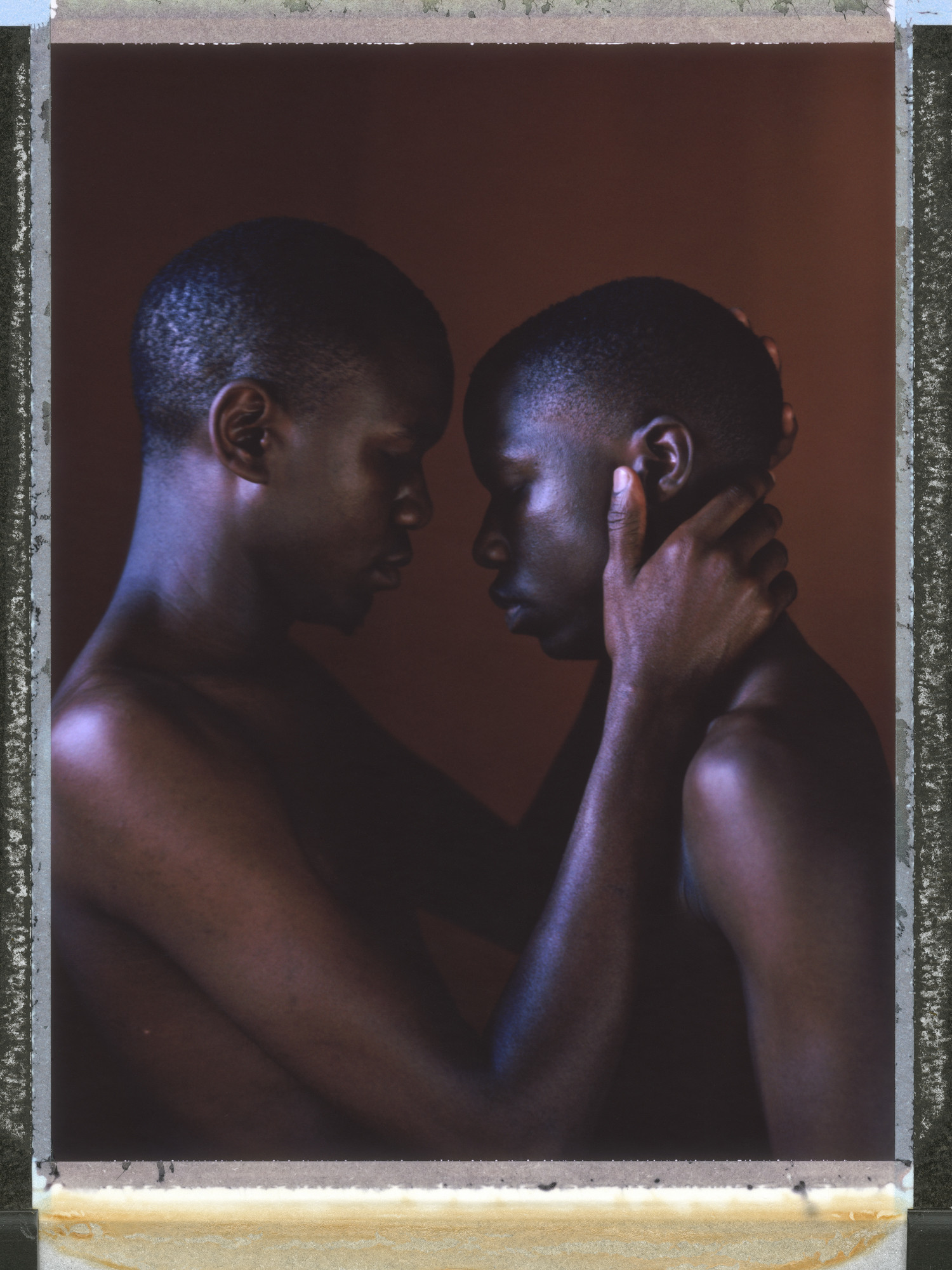

A bare-chested young man wearing only jewelry holds a transgender woman wrapped in cloth the color of rose gold. The woman’s fingers twist themselves in her companion’s two necklaces, her palm obscuring a broad tattoo covering his upper chest. Her head rests on the slope of his neck as his hand and bracelets graze her thigh. Only his eyes, gazing warily beyond the perimeters of the image, interrupt the romance of the frame, suggesting that their moment of peace has been snatched.

(Photo: Jarren Vink/Pacific Standard)

The man, Bobby Brandon Brown, is a gay man in Jamaica. By his own account, he has been physically attacked multiple times for his sexuality; he is homeless and estranged from his family; he has sex with strangers to survive, and has tried multiple times to take his own life. Despite the hardships he faces day to day, this picture of him and a former partner, named Persion Unapologetic, feels intimate, removed from his daily struggle. “I just need people to understand that us LGBT people are loving, caring, and wonderful,” Brown writes in a story displayed alongside the image.

Brown’s photograph is one of the 80 portraits that photographer Robin Hammond has captured for his series Where Love Is Illegal, which shares the images and stories of LGBT citizens from some of the dozens of countries worldwide where homosexuality is criminalized. Hammond is an award-winning photojournalist—he has earned a World Press Photo prize and the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for his work, among others—but each image in Where Love Is Illegal represents an artistic collaboration between Hammond and his subjects. They choose their clothing, poses, and expressions; they write their own stories; and, after the images are taken on a large-format Polaroid camera, Hammond gives his subjects the option to destroy them. The images that survive are shared, along with testimony, on the project’s Instagram account and website, which asks for visitors of all countries to share their stories of discrimination. That inclusive approach aims to amplify the voices of those who are traditionally silenced.

The ultimate goal, Hammond says, is to have LGBT people seen, heard, and valued within their own communities. “Stories are the way that we relate to each other and to our world. So I hope that by having stories coming from this marginalized group, they can challenge hostile narratives about their lives,” Hammond says. “As many of them tell me, the aim is to be treated the same as anyone else.” —Katie Kilkenny

(Photo: Robin Hammond/NOOR)

![Transgender woman Sally, who has been in Lebanon for seven months: "I ran away from Syria because I was running away from ISIS. One of my family members is now with ISIS. Because of him, I ran away here. He was in charge of investigations in ISIS. They want to catch and kill the gays. My last partner was kidnapped and interrogated by ISIS. I'm 90 percent sure they killed him. To kill someone they will choose the highest building and push him from it. They are worse than the Syrian investigation services. The gay people are treated as if they have a contagious disease. In Islam you are given the chance to ask for mercy and to re-enter Islam and follow the Islamic law. But ISIS considers [homosexuality a] a contagious disease, so that's why they kill them."](https://psmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/har2015002p0306-0056-768x1024.jpg)

(Photo: Robin Hammond/NOOR)

(Photo: Robin Hammond/NOOR)

![Yaounde: "I lived a peaceful life with my sweet and loving mother in the big city of Douala, Cameroon, in the year 2012. Our life was peaceful, calm, and reserved, but all changed suddenly when two gay friends [visited] my mother's apartment when she had traveled. This left all the tenants in the knowledge of my hidden homosexual status. When mummy came back from the village, she was broken and destroyed, and after a good time she asked me if I entered into witchcraft."](https://psmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/har2015002p0126-0017-768x1024.jpg)

(Photo: Robin Hammond/NOOR)

![Badr: "The worst moment of my life was in December of 2012. The first president of [Damj, a Tunisian non-profit for human rights that Badr helped to found] received death threats, and I was hiding him in my home to protect him. So I became the target of a group of homophobic gangsters who infiltrated my home in the medina of Tunis; they took my archives and many documents of the non-governmental organization after having violently brutalized me."](https://psmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/har2016005p-0007-795x1024.jpg)

![A posed portrait of lesbian couple O (27, right) and D (23, left): "After [men attacked us for being lesbians], I felt even more strongly how dear D is to me, and how scary the thought that I could lose her. The worst thing that I felt was an absolute inability to protect the one I loved, or even myself. Yes, now I look back on the street and look at every passing male as a possible source of danger. I realized that there are defective people who can pounce on us just because we are lesbians. But every time, now when I'm in the street, when I take her by the hand, I do it consciously, it is my choice. D, hold my hand, this is my reward for your courage."](https://psmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/har2015002p0130-0036-768x1024.jpg)

![Maximus Bloo, Tunisia: "Young kids who found out they're gay and [are] still discovering their life, they often get blackmailed by people such as [an older man I met on Grindr who blackmailed me] and pushed to be turned to a material and a tool for old people and other people to have fun with."](https://psmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/har2016005p-0019-797x1024.jpg)

![Salah Barka, Tunisia: "When my brother told [my mother] that [I was] homosexual, at first she didn't understand because my mom has never been to school, so my brother explained that her son is having sex with other men, and she said, 'And so?' My brother then told her that everyone is talking about it, and she replied, 'As long as he doesn't bring the police to our home, he can do whatever he wants with his life,' and that was a real shock to me, like a slap in the face. It was not a normal reaction to me, because I was expecting a war, the end of the world, or being beaten up."](https://psmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/har2016005p-0013-791x1024.jpg)

(Photo: Robin Hammond/NOOR)

(Photo: Robin Hammond/NOOR)

(Photo: Robin Hammond/NOOR)

(Photo: Robin Hammond/NOOR)

(Photo: Robin Hammond/NOOR)

![Amanda (not her real name), Cape Town, South Africa: "Now I hate men so much because of what happened to me [a man raped me because I was a lesbian]. I feel afraid for my child to go outside because it is dangerous out there at night. But I hope I will be OK one day because [my rapist] got what he deserves, he has been sentenced to jail. I love God so much because he protects me and looks after me all the time. He always looks after me during bright times and dark times. People say it is wrong to date the same sex, but to God, we are all his people, and I truly know that Jesus loves me. Amen!"](https://psmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/har2015002p0130-0032-768x1024.jpg)

A version of this story originally appeared in the December/January 2018 issue of Pacific Standard.