This story began with a pitch from my editor (writers love it when editors do the pitching), which was, simply, to have a conversation with Van Jones, the author and CNN commentator who went viral during the 2016 presidential campaign season. In the immediate wake of the election, Jones was among the few to register liberal/progressive angst in real time in mainstream media and to provide, in several notable appearances, lucid instant analysis (coining terms like “whitelash” on the spot) as well as consolation for those traumatized by Donald Trump’s ascendance. In one remarkable performance, delivered in the sleepless hours after the Rust Belt delivered Trump to the White House, he gently coaxed the left back from the ledge. “Take some time to grieve and heal,” he said, in an iPhone-jittery close-up posted on his Facebook page. He spoke extemporaneously—at once empathetic and coolheaded—straight to the left’s forlorn soul. Just when we needed it most, he played the role of comforting elder brother or uncle, the veteran organizer who’d had his own political dreams dashed on many occasions, only to rise up and fight again (by many accounts his lowest point was his forced resignation from a plum advisor position, dubbed “Green Jobs czar” by the media, in the Obama White House in 2009). Other viral moments include not one but several take-downs of conservative CNN commentator Jeffrey Lord (who becomes visibly nervous whenever Jones raises his voice—moments impossible not to read through the prism of race) and rhetorical fisticuffs with the likes of reactionary pundit Mary Matalin that make for arresting live television and modestly echo the golden era of American public intellectualism, such as Gore Vidal versus William F. Buckley Jr. live from the 1968 Chicago Convention (though most of today’s commentariat lacks the erudition of those days and minds).

(Photo: Joe Toreno; Grooming: Jessica Chu)

Jones and I share some deep history. We are both the subjects of a story more than five centuries in the making, which can be traced back directly to conquest and slavery and the cruel social justifications that normalized it all. Colonialism is the nightmare people of color can’t wake up from, a wound that is reopened every time a Trump figure appears with rhetorical venom (and now, the embodied poison of policy). There’s just nowhere to hide from this history.

Had I sat down with Jones before the election, our conversation probably would have flowed in the direction of a comparative exchange between two men of color with largely aligning generational, political, and even spiritual experiences. But on November 9th, a world yawned open in which many people who look like Jones and myself suddenly felt ourselves strangers—or horrifically familiar. We’d been racially branded as “other” yet again, cast out of what now seemed like the multicultural fantasy of the Obama years. There was an overwhelming sense of splintering and vulnerability. Only a few years earlier, the Obama coalition had been mobilized by hope for change. And some things undeniably did change, particularly in the realm of pop culture. Trevor Noah, Modern Family, #OscarsSoWhite, Girls, Hamilton: Representations of erstwhile “others” moved from the periphery to the center. Given the dearth of diversity among the chattering class, Jones himself was a sign of this arrival.

As an advocate and agitator, Jones has covered some ground. The 48-year-old native of rural Tennessee wandered around the progressive agenda as a young organizer—juvenile justice, environmental justice, police abuse, income inequality. Failures came as often as successes in these ventures, and the struggles led to what he himself has caricatured as everything-and-the-kitchen-sink spirit quests, roaming across black liberation theology, Eastern mysticism, and mindfulness.

While Jones dabbled in radical politics, flirting with Marxism and employing confrontational tactics in the Bay Area after earning his law degree at Yale University (aggressively pinning responsibility for police abuse on liberal icon San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, for example), he also carried deep within him his Tennessee roots—of “sweaty black churches,” as he puts it—the son of politically progressive but deeply religious parents. Over time, he pulled back from the hard-left style of his youth and moved closer to the political center. To some, it was a necessary accommodation, the classic pivot to working within the system (though others would judge him more harshly).

After his short stint in Washington, Jones moved to Los Angeles and now occupies a regular niche in the media landscape as a commentator for CNN. I visited him at his home in the heart of the Silver Lake district, which is the place where I grew up, but in name only. It is now ground zero for the gentrification taking place in the neighborhoods around downtown. There are only vestiges left of the mix of race and class that I experienced, or what was once the city’s pioneering gay and lesbian scene. We talked in Jones’ kitchen and in his den, where somewhat untidy bookshelves held hundreds of titles, the strongest genres being religion and spirituality, politics and political biography, and ecology. He flippantly dismissed my first question, about gentrification in Silver Lake, saying, “That’s your issue, not mine.” Ultimately it was ideas about spirituality and morality that formed the axis of our conversation, and something of a tug-of-war over how the American left should respond to the upheaval of the Trump era.

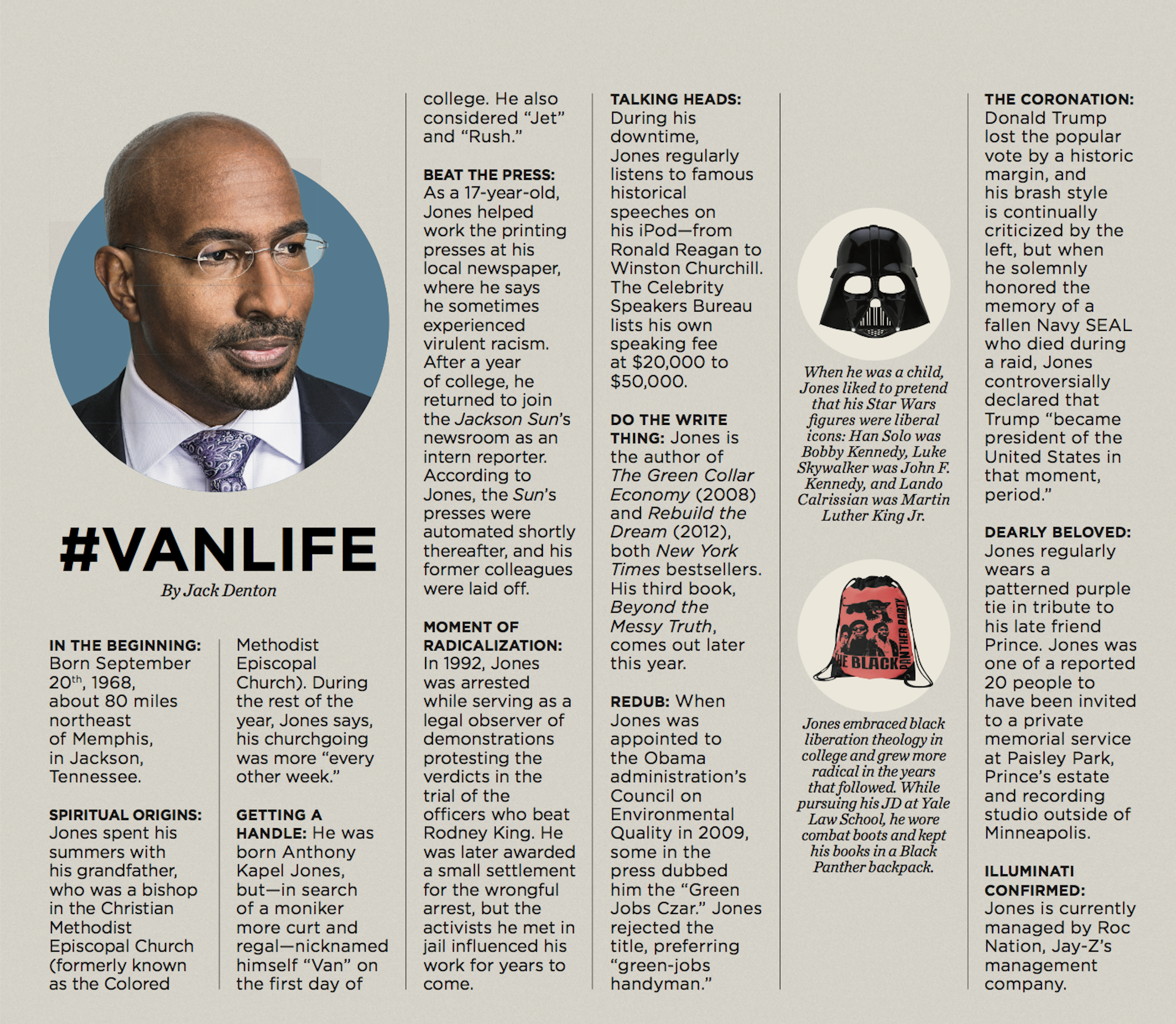

He began the conversation dressed casually in a T-shirt, but spiffed up for the photo shoot and his afternoon meetings by donning a suit and his purple paisley tie, still in mourning for his friend Prince, several months after his death.

There are two periods of your life I’m curious about: the moment after Proposition 21 passed in California—the tough-on-crime ballot initiative that you organized against in 2000—and then after your departure from the White House in 2009. You’ve described both of these as moments of depression, searching. I was struck by how political failure became spiritual desire for you. How would you describe your religious and spiritual experience as it relates to these moments?

I come out of the same faith traditions that the civil rights movement itself came out of—the black church in the South. The black community’s the most religious part of the country and of the Democratic coalition, and it’s because it’s the one institution that we were allowed to have, to lead, and defend in a Christian country. For a lot of white liberals, the church is a site of oppression and hierarchy, and they flee to drugs and bohemian lifestyles for their liberation. For most middle-class African Americans, we see the drugs and irresponsible lifestyles as the oppression, and flee to the church for sanctuary, and for freedom. And so that creates a lot of misunderstanding within the Democratic coalition about the role of faith and faith institutions. The only two places I ever felt 100 percent welcome as an African-American man in this country: No. 1, any black church, and No. 2, Paisley Park [Prince’s Minneapolis compound]. Otherwise it’s always negotiated space. But if you’re a woman and you’re gay, even the black church is negotiated space too often, so I recognize the privilege I have as a man.

The centrality of the black church as an institution that was created during our enslavement and has persisted is, I think, hard for people to understand. And then there’s the particular kind of theology that is native to the black church, what I call hallelujah-anyhow theology: Even if we lost our job, even if we’re living in a housing project, even if we’re poor, even if our father’s in prison—hallelujah anyhow. The search for a kind of joy—not happiness—and the preservation of dignity and the connection to something sacred no matter how terrible the external circumstances, that hallelujah-anyhow bedrock faith is something that is also misunderstood by people who don’t have to do it and don’t have to rely on that in their journey in the same way.

In the Latino experience, we have the discourse of sanctuary, which flowed out of the solidarity and non-interventionist movements during the civil wars in Central America in the 1980s, and which took inspiration from Latin American liberation theology. The concept of sanctuary, which is very solidly Christian, arrived in white progressive communities during that time, as refugees of the Central American conflicts were welcomed, and is now used by local governments secularly, as in “sanctuary cities,” but it still carries the moral authority of Christian faith. That seems to be one of the few instances where Christian ethics have been front and center in American progressive politics since the civil rights movement. Do you think the moral authority of the church needs to come back into liberal and progressive discourse?

(Photo: Joe Toreno)

It’s going to come roaring back. Look at Reverend William Barber in North Carolina leading the Moral Mondays movement. He spoke at the Democratic convention and all these secular atheist progressives were weeping. There’s power there that’s undeniable. You can rationalize all you want to, but if I put your atheist butt in that chair, you will find something stirring in you that you can’t explain, and that power is going to have to be unleashed as a counter to Trump. The #LoveArmy campaign I’m leading now is about challenging hate and reclaiming love, because love has become such a wimpy, schmaltzy, Hallmark card kind of term that people think of as too weak of a response. I don’t know what kind of love you have in your life, but love is the strongest force in my life, and the strongest force in the universe. A mama bear loves her cub—you better not mess with that cub. That’s the kind of love that’s required if you love this country and you love the constituencies that [Trump is] targeting. You have to take a stand, but it’s not about saying “I hate Donald Trump.” Dr. King says you should never let a man pull you so low as to hate him. I think Donald Trump is a despicable clown car of hypocrisy and greed and he might be much worse than liberals fear, but I think his voters are much better than liberals know. Most of the people who voted for Trump did not vote for every crazy horrific thing he said. Just like those people who voted for Hillary Clinton didn’t vote for everything she’s ever done or said. People voted for Trump for a mix of reasons.

What is heartbreaking for most people is that his inflammatory and divisive rhetoric wasn’t disqualifying for all Americans. But then people jumped to the conclusion that it was therefore delightful to 60 million Americans—that’s also not true. There were a lot of people who voted for Trump who found his rhetoric distasteful but not disqualifying. In other words, they aren’t saying, “I too hate all of these groups—Mexicans, Muslims, etc.” They aren”t saying that at all. They’re saying, “I don’t hate ’em but I don’t like ’em enough to change my vote based on how they feel.” That’s heartbreaking, but the lack of solidarity doesn’t mean the presence of actual hatred.

Liberals have a binary view on bigotry: You’re either a racist or you’re anti-racist, you’re either a sexist or anti-sexist, nothing in the middle. A liberal sees a bigot and anyone supporting the bigot as a bigot. That only makes sense in a liberal, binary paradigm. If you have a more nuanced paradigm about human behavior, then you say, well, there’s probably a range here. There are people who are outright bigots, like in the Klan, who love Donald Trump, all the way over to “God, I hate that he said that stuff but I just can’t support Hillary Clinton.” And all of those are Trump voters. So then if you say, “If you voted for a bigot you’re a bigot,” you’re building his coalition for him. You’re actually taking people who are more ambivalent or even more with you on the inflammatory stuff and insulting them and giving them to Trump. Which is bad strategy, and also immoral, because we’re all more than our vote. A bad vote does not make you a bad person, and your bad vote is not going to make me a bad person by making me hate you. These are the kinds of moral issues I approach out of my deep spiritual grounding, and the faith tradition I come out of.

How have religion and politics come together for you through the years?

Even when I was a hardcore leftist with Marxist commitments I never stopped being a Christian, because it’s too core to who I am, too core to my sense of what the liberation struggle is about. So I was always the one Christian in the Marxist study group. And as I burned out on all the far-left head-banging against the hard wall of the establishment, I tried to figure out other ways to heal myself and be of some service. It was very easy to find all the New Age currents in the Bay Area. I began to sample and surf those as well. Everything from Landmark Forum to Science of Mind to…

Ayahuasca?

No, not that far. Buddhism, Hinduism. Not Islam yet. But, you know, I went to services, to Buddhist retreats, spent a lot of time at Spirit Rock and other retreat centers, read a lot of books, did a lot of counseling, because you can burn out really badly doing non-violent urban warfare. You can really mess your health and your emotional state up—and I did.

My theologian friends talk about negative knowledge, apophatic learning—essentially how illumination comes in the darkness of struggle.

I’ve had a lot of success in my life and a lot of failure. You learn a lot more from failure, and if you have big, big failures like I’ve had you learn invaluable lessons.

So, if that’s the case, can we say the country is in the dark night of its soul?

I think so. You know, in general, breakdowns lead to breakthroughs, and there was a liberal arrogance that had to have a comeuppance. Hillary Clinton’s campaign was the most cynical expression of liberal elitism and the downsides of that kind of multicultural worldview that you could find. We assumed in the Democratic Party that we were headed for a referendum on bigotry for the Republican Party. But at least in the Rust Belt where we lost, it became a referendum on elitism and a certain kind of multicultural snobbery in the Democratic Party.

Your series The Messy Truth began with you seeking dialogue with Trump voters, and trying to bridge the chasm between Van Jones, who the right mostly sees as an identitarian leftist, and working-class whites. You literally walked into their living rooms and talked to them. While you were doing that, I was hanging with undocumented students and their allies who use rhetoric like “non-conforming bodies” and “non-binary sexuality.” There’s such a huge gap between those groups—I’m talking about radically different languages. How, or can, or should we bridge that?

You don’t bridge it through the head first, you bridge it through the heart first. And it takes time. I think the civil rights crowd and the women’s rights crowd and all these sort of egalitarians, they fail to appreciate the heroism of their own cause. For 10,000 years, chopping someone to bits because they were from a different tribe was not a bad idea, it was the requirement of, you know, life on this planet. So the idea, which is my idea and your idea, that your tribe should be seven billion people? That’s a tough one. And the fact that every step along that process there’s a backlash is not some failure of the movement or some reason for disappointment, it’s just the way the thing works. You have slavery and you have the Civil War, and you have Reconstruction and 100 years of segregation, and then you have this beautiful civil rights movement, and so this thing rocks back and forth, but the center moves. Trump isn’t saying that he’s going after marriage equality. For years, Obama was afraid to say that he was for marriage equality. Now the worst demagogue to ever run for office will not attack that. Now, for both political parties, it’s a fait accompli. So, it rocks back and forth, but the center continues to move.

The moral arc of history bends toward justice.

Yeah, and so, these setbacks, we shouldn’t take this hard. We should be much more impressed with the miracles we create than when, inevitably, some of the less pleasant parts of humanity reassert themselves. In other words, the flight is more interesting than the gravity. That would be my argument to the young people: Your insistence that we soar is a miracle, and the fact that some people point out that there’s gravity and sometimes tug you back toward it, that’s mundane—that’s 10,000 years. These kids are a miracle and what they expect and what they insist upon is a miracle and it’s important for them to appreciate that because it will get them to be more humble about the claims that they are making.

But isn’t it the 20-year-old’s job to push the center?

Yeah, but it’s important that they deal with the fact that there is gravity. Let me just say something which I think shouldn’t be as shocking as it is to hear from a black civil rights guy: We are shoving a lot of change down the throats of tens of millions of white guys who don’t have to necessarily like it all the time. I don’t just mean in the United States, I mean across the West. It’s a massive amount of change on gender, on sexuality, on race, on geopolitics, on technology, on the economy, and surprise, surprise! Some of them are belting it back in our face. You’re insisting on this pace—and these young people are the worst, because they will call you a bigot for not believing something that they had never heard of three months ago. So with that level of arrogance and lack of understanding, the blowback is not only inevitable, but you’ll actually accelerate it. What’s missing? Mandela. Mandela was both tough but warm. Mandela wasn’t in jail because he was a Gandhi figure. He was in jail because he said enough is enough.

You mean what’s missing is a leadership figure like Mandela or…?

The spirit. That spirit of Mandela that says, even though I am oppressed, my view of the perfect society has a place of dignity for you in it. That was Mandela. Mandela said, I’m Xhosa—I’m not Zulu, I’m not Fula, I’m not Afrikaner—but the South Africa I have in my mind has a place of dignity and honor for all of you, all of us, and I’m actually fighting for that. When he goes to jail, what does he say? “I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination.” That position: that everyone in my country will have a place of dignity and honor. If you’re a white guy in a red state who voted for Trump, I’m not fighting against you, I’m fighting for you, because I want you to have a place of honor that doesn’t require you to indulge in hatreds that are beneath you and your family.

I’m right, you’re wrong! I’m awesome, you suck! We’re good, you’re bad, we want to win!—that is now the position of the left and the right and everybody in the middle. And so, you have essentially a rich person’s civil war. What’s missing is the Mandela spirit—but that can come from these young people. These young people can actually rest in the inevitability of their victory, as Mandela did, and let that get them grace. You can rest in the inevitability of your victory and therefore show grace. It is in fact the case that 20 or 30 years from now it won’t be so weird if somebody’s polyamorous, bisexual, trans. There’ll be enough of them on television and in elective offices that it won’t be that big a deal. Your victory is inevitable, and since it is inevitable, you can show grace to your quote-unquote oppressor. When I tell these kids this they always say, “This is terribly unfair,” and I say, “Yes, it’s absolutely unfair—and necessary.” It is unfair and necessary for the oppressed to take moral account of the needs of the oppressor.

(Photo: Joe Toreno; Grooming: Jessica Chu)

But you’re asking them to think through your experience. It might take them until they reach your age before they get there.

Or we just train them that way from the beginning, as opposed to this post-structural post-modern bullshit that we feed these kids. You want to be honest about these goddamn campuses? You’re producing wave upon wave of arrogant kids who can critique and deconstruct literally everything but they can’t reconstruct anything. That’s the big problem.

It’s hard not to take this personally. By this point, a tension seems to have developed between us. I think he’s letting Trump voters off the hook too easily, not holding them accountable for normalizing what is plainly racist discourse, and he’s criticizing young radicals for using the kinds of critical tools that professors like me are trying to impart. He almost sounds like he’s counseling a version of “go slow.” Maybe this is a sign of Trump’s America—in which the liberals and identitarians rail against each other, a cannibalistic feast that will cast the left off into the wilderness for a generation. Maybe our conversation is an embodiment of the general state of the American left today—wounded, confused, searching. I want to agree again on something, so I move toward what I think is neutral territory, somewhere where we might both see a sign of progress.

Your name has been all over the environmental justice scene for a long time. I’d like to think we’ve come a ways since the mid-2000s, when mainstream environmentalists were more likely to complain about the water bottles migrants discarded in the desert than the humanitarian crisis of the migrants themselves.

The environmental movement is the only progressive movement in the U.S. that is explicitly racially segregated. There are mainstream environmental groups and there’s environmental justice. Mainstream environmental groups have $100 million budgets and environmental justice groups have $100,000 budgets. Environmental justice groups are almost entirely people of color and women serving the poor, and mainstream environmental groups are almost entirely led by white men catering to rich donors. And it is a stench in the nostrils of God that we have this kind of explicit racial segregation in a largely progressive movement. It is a moral catastrophe that leads to political catastrophes, like what you saw in 1997 in Nevada, where the white-dominated solar industry went and got all these solar subsidies, and the polluters went and got all the poor people and poor people of color to knock all those solar subsidies out because they didn’t benefit poor people, didn’t benefit people of color. They only benefited rich wealthy people who could put them on their mansions, and now solar’s essentially been stalled out in Nevada, one of our sunniest states.

If you do eco-apartheid as your fundamental politics, where you have ecological haves and ecological have-nots, you wind up with eco-apocalypse because you can’t sustain it politically. These guys talk about sustainability environmentally, but they don’t understand sustainability politically, which means you have to get everybody a stake in the outcome. In California, we’ve done it the right way. Our cap-and-trade program has taken a billion dollars from polluters and put it directly into poor people’s pockets through a fund that allows cheap and low-cost solar panels, bus passes, carpool services for migrant workers, etc. So, if you do eco-equity as your fundamental strategy, you’re going to build a green economy that’s strong enough to lift people out of poverty. Republicans support our cap-and-trade program in California because poor Republicans are benefiting from the program.

When you have encounters with Jeffrey Lord or Mary Matalin, those viral moments, are we moving the discourse forward meaningfully or just spinning in a media rat wheel?

I don’t have any idea. It’s not my job to worry about that. My job is to sit there and say what I think, and to do so in a way that’s authentic and hopefully constructive. But if Mary Matalin decides to pick a fight with me on the air there’s nothing I can do about that. I don’t think obsessing about what happens in the media and trying to turn it into this whole big theory of reality is what I’m paid to do. I am paid because I’m a clever boy who can speak well on television, and I have these cheekbones. That’s my job, and so I am going to speak as authentically as I can. If they say something that I think is horrific and horrible, I will disagree with it. If they say something—even if they’re Republicans—that I agree with, I’m going to agree with it. I’m going to try to be authentically in the conversation. What I’m not going to do is come on with my preloaded talking points and no matter what that person says just use that opportunity to fire them off. I think I’m at least speaking authentically, and looking for common ground, and for new things to say—because I don’t want to repeat the same thing all day on TV. I rarely repeat myself. I’m trying to authentically create new insights, new understandings, and offer them up into the marketplace. Some of them go viral because they’re clever. Some of them go viral because they’re hot. Some of them just fall into the nothing of the vast digital detritus of life.

Have you ever come close to walking off the set, the equivalent of a mic drop?

It’s too hard for black people to get on television for me to walk off.

I’ve given some thought to the fact that this is a conversation between a black man and a brown man, that we by default represent the politics of our respective communities, which don’t exactly form an easy coalition. But it would seem to be a political, if not a moral, imperative to try to create a more profound one.

If the country has a future, it will be largely on the broad shoulders of the black and brown communities working together and trying to get the whole country to a better place. I don’t think there’s any formula for progress that doesn’t center itself on the needs and aspirations of the African-American and Latino communities as a political bloc and also a moral bloc that stands as the underprivileged, left-out, and screwed-over constituencies, including the white guys who often don’t like us very much. I don’t think we should be fighting against white workers—we should be fighting for white workers. I don’t think we should be fighting against the poor coal miners—we should be fighting for them. Because at the end of the day it’s that Mandela principle: Our victory is inevitable demographically and morally. The victory is inevitable. We may get a big setback of 30 years, but eventually you’ll wind up with a West that is multicultural, a West that has women and queer folks. Just look at the numbers. The West is going to be a browner West. There may be 30 years of real conflict over it, and there may be times when the backlashers have power and do all kinds of horrible things, and there will be great suffering. But eventually there’s going to be a lesbian of color in the White House. That’s going to happen. And by the time it happens it’s not going to be a big deal.

A version of this story originally appeared in the August/September 2017 issue of Pacific Standard.