Vijay Iyer is changing the face of jazz music, quite literally. Well-known American musicians in the genre tend to be white or black, not Indian American. But in the two decades that the musician, composer, and Harvard University music professor has been playing professionally, Iyer has become one of jazz’s most important contemporary figures. Iyer says his aim is to perform music that emphasizes dialogue between many collaborators. In live shows with his trio or his sextet, Iyer performs homages, improvised or composed, to predecessors like John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk. He is also known for collaborating with artists in other mediums—including poet Mike Ladd, writer and photographer Teju Cole, and filmmaker Haile Gerima—and often uses his art to champion empathy for underrepresented communities. His 2012 project with Ladd, Holding It Down: The Veterans’ Dreams Project, incorporated the dreams of veterans of color from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; his latest album with his sextet, Far From Over, includes several pieces recorded in response to police violence against communities of color; and, in his courses at Harvard, Iyer pushes his students not to think of the West as the center of the world as they study music history. Iyer is making the case, onstage and in the classroom, that jazz is a genre to watch in its push for justice and equality in 2017.

Books

Blind Spot

Travel books often highlight the unique experiences and cultural oddities a destination has to offer in an increasingly globalized world. Not so in Blind Spot, photographer and writer Teju Cole’s compendium of photography and prose released in June of this year. Cole highlights recurring visual motifs in cities all over the world to illustrate, as he puts it, “the continuity of places.” Along with the over 150 images he has selected for the project, Cole included equally original captions—long musings on art, music, and history—to unveil hidden, unexpected, and personal meanings behind his chosen images.

Why

“These are photos [Cole] took where he was noticing a confluence of factors; it might be the back of someone’s head, or it might be just a canoe abandoned in the sand. But then he’ll tell a story about this place, this moment, or this experience, and it will suddenly reveal the hidden depth inside of the thing. Often it’s harrowing—some kind of political truth or moment of terror that happened there once or recently that is somehow embodied in this frame.”

In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition

It’s a matter of historical record that improvised jazz is a deeply African-American art form. But in his 2003 book In the Break, poet and performance studies professor Fred Moten argues that African Americans didn’t confine these elements of spontaneity to their music: They extemporized black culture, politics, and identity too. With In the Break, which analyzes the music and words of Duke Ellington, Cecil Taylor, James Baldwin, and Adrian Piper, among others, Moten shows that all aspects of “blackness” require some degree of improvisation.

Why

“There’s one chapter I’ll revisit over years and basically have a different experience with each time. I think that it’s important to just allow that difference, that the same work might lead you on a different path each time, especially with works that generate a multiplicity of meanings and interpretations. When I give it to my students, it can enrage them but also inspire them: Enrage them because it’s challenging to work through, but it’s also something that’s transformative as an experience, because it brings you to the brink of your own understanding.”

Song

“Trinkle Tinkle”

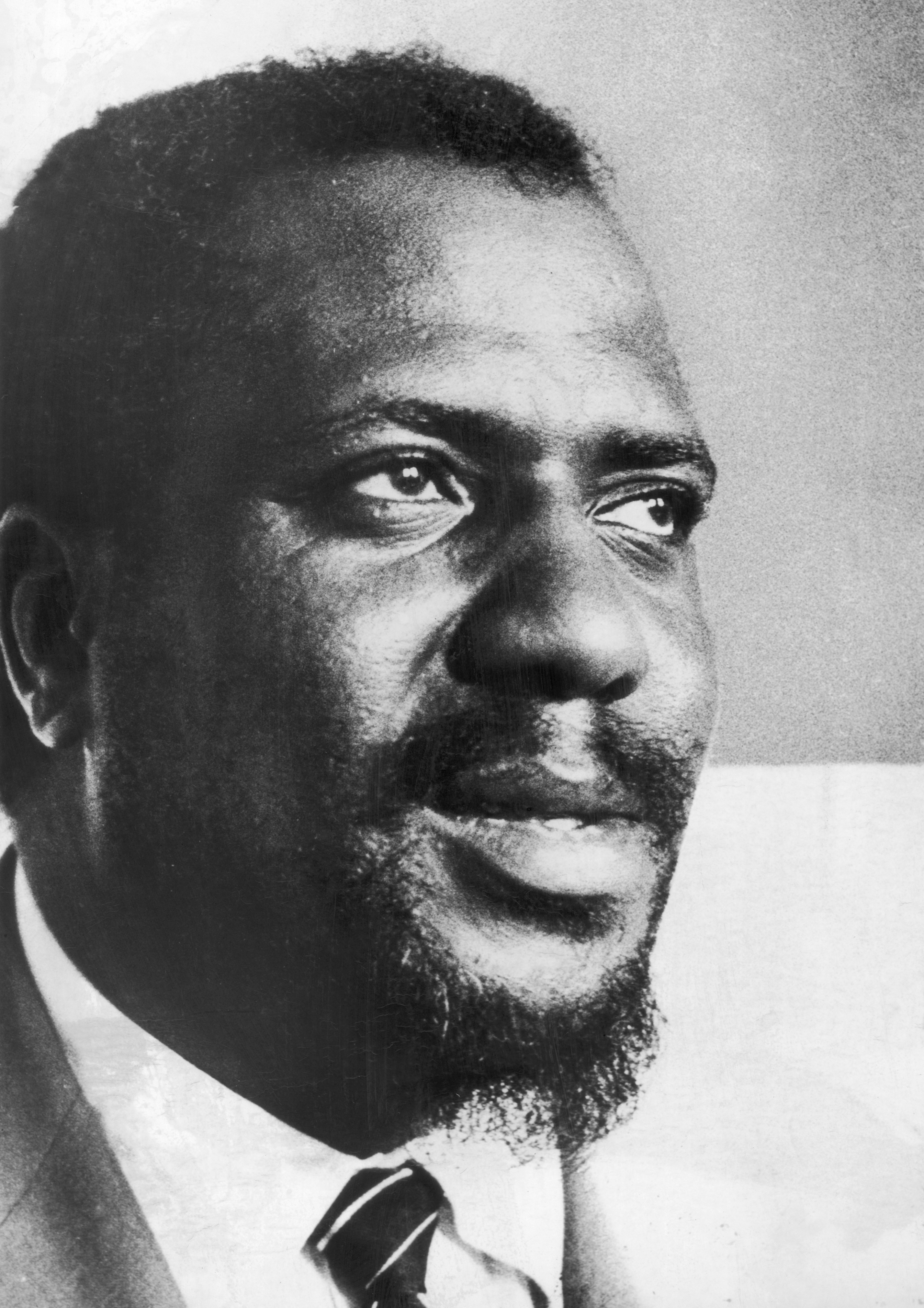

Thelonious Monk’s “Trinkle Tinkle” was originally recorded starring the piano, but the song’s most famous version might be the recording Monk made with John Coltrane on the saxophone in 1957. A virtuosic and wickedly fast performance, the song has “become the modern test of one’s worth for tenor saxophonists” since Coltrane played it, as saxophonist Sean Coughlin wrote in 2009.

Why

“The thing about a wind instrument is that, because it’s supported by the breath, there’s this intuitive connection with the human voice. To hear it played on the piano is one thing, because then you hear the trace of the hand on the keys, but [when] it’s embodied on the saxophone in that way, it launches [Coltrane] into a more open space for improvising. The way he plays with it is this vivid, electrifying series of statements. That’s one I always go back to.”

Musician

Prince

One of the best-selling artists in music history, Prince—né Prince Rogers Nelson—released over 40 albums in his lifetime, won seven Grammys, and was inducted to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2004, on his first appearance on the ballot. Though his lyrics are perhaps best known for their sexual frankness—Tipper Gore has said that his sexually charged 1984 song “Darling Nikki” inspired her to form the Parents Music Resource Center, which called for Senate hearings on provocative rock lyrics—the musician was also notoriously shy and reclusive. Prince died in 2016 from a fentanyl overdose, and his estate, Paisley Park, opened its doors last year as a museum.

Why

“We get attracted to pop icons for various reasons, but for me it was really about the way [Prince] put music together. He would take his time building a song because it was meant to work on the body. It wasn’t just a song that would stick in your ear, or that you’d sing to yourself—it would [make you] move a certain way. He could have a groove that could last seven or eight or 12 minutes and, across that, these different episodes would emerge. There was a way that his music could conjure a multitude and tell many stories, and support many stories, and many kinds of presence.”

Cinematographer

Bradford Young

Some of this decade’s most striking films owe their visceral beauty and atmosphere to cinematographer Bradford Young. Before Young was hailed as a rising star for his Oscar-nominated work on Arrival, he supervised the visuals of lower-budgeted films, including Selma, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, Pariah, and A Most Violent Year, and he has been outspoken in citing cinematographers of color like Ernest Dickerson, Arthur Jafa, and Malik Sayeed as his inspirations. Now, he’s working on the upcoming Han Solo standalone Star Wars film with director Ron Howard—quite a departure from his predominantly art-house filmography.

Why

“Really early on, and in the last couple years as he’s become more prominent, [Young] was very vocal about how the way that people of color were presented even visually onscreen, and how historically Hollywood films have not known how to light brown skin. Usually the normative ways of lighting a scene favor white skin, [and so] darker people were either washed out, or too dark. He’s been, in his own way, a kind of activist, literally making people of color visible in cinema.”

Poet

Yusef Komunyakaa

Yusef Komunyakaa looms large among Vietnam War poets: As a war correspondent for the 23rd Infantry Division’s newspaper The Southern Cross, Komunyakaa sometimes found himself on the front lines of the battle. He wrote about those experiences in his 1986 poetry collection I Apologize for the Eyes in My Head, and later in more detail in 1988’s Dien Cai Dau (its title comes from the expression for “crazy” in Vietnamese). Iyer read Komunyakaa while he was preparing his project with performer Mike Ladd, Holding It Down: The Veterans’ Dreams Project.

Why

“Most film portrayals of veterans make them all white—[Holding It Down] was specifically about veterans of color, for that reason. We know that, in an all-volunteer army, and in an economy like ours, people of color, who often come from the lowest economic rungs of society, feel compelled to enlist for reasons of need or perceived need, or because they feel they have no other choices. In the case of Vietnam, it was about who was able to dodge the draft [and who wasn’t]. It was useful for us with that project to listen to stories not in film, but in the realm of poetry.”

Musicians

The Trio of Muhal Richard Abrams, George Lewis, and Roscoe Mitchell

Once called the “architects of modern music,” Muhal Richard Abrams, George Lewis, and Roscoe Mitchell have been pushing the boundaries of jazz together since the 1970s; the three are pioneering members of Chicago’s legendary Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. After four records and several decades of live performances, the trio have developed what they call “open” improvisation, where musicians aim to use restraint and trust to create a dialogue; the problem with “free improvisation,” they say, is that some players can occasionally siphon attention away from others. The result of the trio’s work creates a mass of noises, unexpected pauses, and sudden shrieks, demanding attention—and an open mind—from the listener.

Why

“I got to curate the Ojai Music Festival in June, and what [Abrams, Lewis, and Mitchell] did in the hour [they performed] there was kind of shocking in the way that it became this revelatory experience—people were in tears at the end. It’s a very vulnerable, raw process of starting from the most basic elements of sound and gesture. Somehow, over the course of this hour, awareness aggregates and shakes you in a way that words can barely describe. Because it’s this experience that everybody goes through together, there’s this kind of mutual awareness that’s a little bit scary because it’s so profound. People aren’t always ready for it, but when they are, it becomes an experience they’ll never forget.”

Cellist

Okkyung Lee

If you think you’ve got a firm grasp on what a cello sounds like, you’ve probably never heard a song by Okkyung Lee. The Korean-born, Berklee College of Music-educated cellist is best known for coaxing unexpected, wild sounds out of the instrument: electric-guitar-like shreds; swarms of shrieking notes; croaks and plucks. Lee has released two albums of solo cello improvisations and has performed with some of the world’s great rock and avant-garde musicians, including Laurie Anderson, John Zorn, Nels Cline, and Thurston Moore.

Why

“If you can ever see her playing live solo cello, it’s a riveting, transformative experience that makes you re-think everything about music and life. I don’t know how else to put it—it’s really one of the most moving experiences I’ve ever had.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the December/January 2018 issue of Pacific Standard.