The Congressional Budget Office released on Monday its score of the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017, the Senate’s plan for repealing the Affordable Care Act. All in, the CBO projects that, by 2026, compared to the ACA, the BCRA would reduce the federal deficit by $321 billion (which is $202 billion more than the House of Representatives’ bill) and increase the number of uninsured people in this country by 22 million (slightly less than the 23 million projected increase under the House bill).

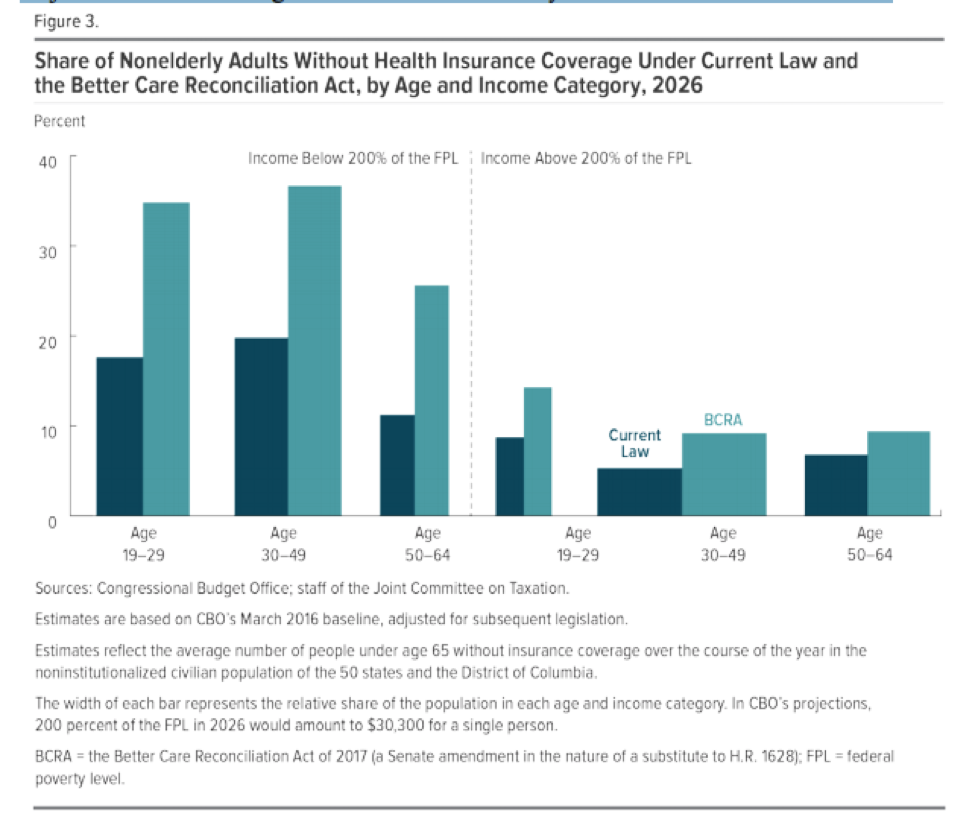

The CBO projects that the coverage losses would begin immediately, with about 15 million more people going uninsured in 2018 due to the elimination of the individual mandate. There would be 15 million fewer Medicaid enrollees by 2026, due to reduced federal spending on Medicaid, and seven million fewer enrollees in the non-group market, due to the elimination of the mandate and because average subsidies for coverage would be lower under the BCRA than under the ACA. As the chart below, from the CBO, indicates, the coverage losses would disproportionately affect older, lower-income Americans:

(While the report doesn’t examine in detail what would happen to coverage after 2026, the CBO does “expect” that Medicaid enrollment would continue to fall due to funding pressures on states.)

The CBO projects that the legislation would initially increase premiums—by about 20 percent in 2018 and 10 percent in 2019—but that average premiums for benchmark plans would later decline. By 2026, average premiums for benchmark plans would be about 20 percent lower than under the ACA. Deductibles and out-of-pocket spending, however, would increase for most people in the non-group markets under this legislation, due to the change in the generosity of benchmark plans and the eventual elimination of the ACA’s cost-sharing subsidies. The CBO report estimates many low-income people would simply choose not to purchase insurance coverage in the face of such high deductibles. People living in states that obtained waivers from the ACA’s essential health benefits requirements could face particularly large increases in out-of-pocket spending.

Eye-popping coverage losses notwithstanding, the CBO score contained some good news for the GOP with respect to market stability: According to the report, non-group insurance markets under the BCRA “would continue to be stable in most parts of the country” due to premium subsidies, cost-sharing-subsidies, and some of the other market stabilization funding included in the legislation. This is true for most of the country even after 2020, which is when much of the stabilization funding (including cost-sharing subsidies) disappears, and in states that obtain waivers from some of the ACA’s regulations. The CBO does, however, predict some issues for the “small fraction of the population” residing in areas in which no insurers participated in the marketplaces or in which premiums were very high. And in states that implement extensive waivers, the CBO predicts that “all insurance in the non-group market would become very expensive for at least a short period of time.”

Of course, the big question now is whether this score will change the odds of the legislation making it through the Senate. The CBO’s projections on coverage losses aren’t likely to thrill moderate Republicans who had hoped their bill would represent a much more substantial improvement over the House bill, and conservatives are also reportedly not thrilled about the CBO’s projections. One thing’s for sure: Mitch McConnell has his work cut out for him.