On January 1, 2015, California hens, according to California law, were un-caged. The official enactment of Proposition 2—an initiative passed in 2008 requiring that hens have enough space to turn around—means that all eggs sourced from California producers must come from birds who have access to nearly twice the space they had before Prop 2 landed.

There are two obvious conclusions to draw from the measure. First, more room is better for birds than less. Second, “better” isn’t necessarily saying much. Before Prop 2, hens were jammed like sardines into battery cages. Prop 2’s expanded square footage—to a minimum of 116 square inches per bird—does nothing to eliminate the inherent stress of confinement. The measure, too few have noted, is perfectly conducive to factory farming.

Do incremental reforms set the industry on a pathway toward increasingly stringent measures that will significantly improve the lives of animals? Or are they token gestures that make consumers feel better?

But between these black-and-white conclusions lies a lot of gray area. How this gray area is interpreted will be critical to understanding the larger implications of Prop 2 and the role it could play in the future of animal welfare. When it comes to the hens themselves, the question at the heart of the initiative—the one that animal advocates debate with rare intensity—is this: What does Prop 2 actually mean for birds?

Several groups see Prop 2’s passing as an obvious cause for celebration. Nathan Runkle, president of Mercy for Animals, wrote: “With the enactment of Prop 2, California is leading the way towards a society in which farmed animals are treated with the respect they so rightly deserve.” The Humane Society of the United States was also thrilled. Wayne Pacelle, president and CEO of HSUS, deemed California “the most humane state in terms of animal welfare policies.” Likewise, about a hundred celebrants recently gathered at the San Francisco Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (along with 20 hens, a rooster, and Pacelle), where they popped champagne and chirped (really) their applause for the measure.

But not everyone is ready to party. A week after Prop 2 went into effect, Wayne Hsiung, co-founder of the animal activist group Direct Action Everywhere, made public the harrowing contents of its undercover investigation of Petaluma Farms, a northern California egg producer. Scathing exposes of industrialized factory farms are common enough, but this one bucked the norm because Petaluma was supposedly one of the good guys. It supplies organic, cage-free eggs to Whole Foods and Organic Valley, and carries the Humane Certified label on many of its products.

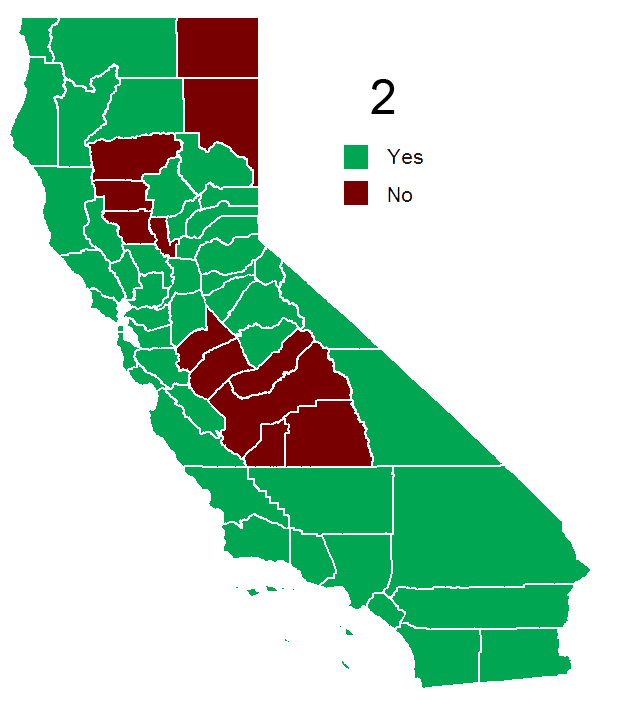

Petaluma Farms opposed Prop 2 back when the measure was being debated in 2008, claiming that eggs would become more expensive. But in a recent phone conversation, Hsiung explained that the conditions he witnessed in the 15 (out of 28) hen sheds he visited at Petaluma would have easily surpassed Prop 2’s minimal space requirement. “Petaluma is a great farm by Prop 2 standards,” he says. Even so, the birds Hsiung encountered—thousands of them—were still “suffering the extremes of confinement.” The video seems to bear this claim out in graphic detail.

Calling Prop 2 a “symbol of progress,” Hsiung nonetheless questions its long-term effectiveness for the birds it aims to protect. “The way it’s characterized,” he says, “it’ll serve as a wall rather than a wedge.” What he means is that Prop 2 will create a false sense of assurance, one that will allow consumers to assume the birds are all right when, in fact, those living on farms such as Petaluma will continue to be in tremendous distress.

Many leading animal advocates agree with the idea that Prop 2 is essentially meaningless for California hens. Gary Francione, a Rutgers University law professor and author of numerous books on animal rights, says that, even under cage-free conditions, “the hens used to produce eggs are still going to be subjected to treatment that constitutes torture.” He criticized those who “are praising Prop 2 as resulting in some sort of normatively desirable situation,” noting how “this amounts to promoting the problematic idea that we can engage in ‘compassionate’ exploitation.” As for the claim that Prop 2 treats birds with “respect,” Francione says, “outrageous.”

As long as consumers want to scramble eggs and not pay out the nose for them, the ultimate outcome of Prop 2 may be far more modest than all those empty cages suggest.

These downbeat assessments raise important questions about the larger impact of animal welfare initiatives such as Prop 2. Do incremental reforms set the industry on a pathway toward increasingly stringent measures that will significantly improve the lives of animals and the farms they inhabit? Or are they token gestures that make consumers feel better about animal products sourced from producers who come off looking like St. Francis of Assisi when, in reality, they are everyday factory farmers only concerned with the bottom line?

Paul Shapiro, vice president of animal protection at HSUS, has thought extensively about this conundrum. For starters, he insists there’s nothing token about the elimination of battery cages. In an email exchange, he writes: “To suggest that cage-free henhouses are comparable to battery cage confinement ignores the reality of how horrific battery cages are.” Cage-free birds, he explains, “have more than twice the space—on a per bird basis—than their caged counterparts, as well as the ability to walk, perch, lay their eggs in a more secluded spot, and more.”

Shapiro never argues that Prop 2 will guarantee “humane” treatment. “It’s one thing if someone wants to argue that cage-free isn’t ‘humane,’” he says. But he believes that “to then make the gigantic leap from there to suggesting that it’s not an improvement for animals reflects a stark unfamiliarity with the unbearably torturous ways most egg-laying are treated.” Prop 2 “was never intended to usher in idyllic conditions for animals,” he says. Instead, “it was an incremental improvement in the lives of millions of animals in the largest agricultural state in the union.”

And that point brings us back to one of the black-and-white conclusions: More room is certainly better. But whether or not this incremental improvement becomes, as Hsiung frames the matter, a wall or a wedge remains to be seen. For now, though, it seems safe to say that as long as consumers want to scramble eggs and not pay out the nose for them, the ultimate outcome of Prop 2 may be far more modest than all those empty cages suggest. The hens, for their part, might be able to spread their wings. But they shouldn’t expect to fly anytime soon.