Hillary Clinton’s proposal to expand the Child Tax Credit is about more than just the middle class.

By Dwyer Gunn

(Photo: John MacDougall/AFP/Getty Images)

Earlier this month, Hillary Clintonproposed a significant expansion of the Child Tax Credit. For political purposes, the campaign has emphasized the proposal’s effects on the middle class. “Hard-working, middle-class families are struggling with rising costs for childcare, health care, caregiving and college,” Clinton said in a press release on the campaign website. While that might be true, the real meat of Clinton’s plan has nothing to do with the middle class, and everything to do with the poor.

Clinton’s proposed expansion would indeed provide a boost in after-tax income for middle-income families with young children. It calls for a doubling of the maximum value of the credit, to $2,000 per child, for families with children under the age of five. That’s about it, as far as the middle class goes.

More interesting is that Clinton’s plan calls for a reduction in the CTC’s refundability threshold (to $0, from its current level of $3,000) and an increase in the credit’s phase-in rate (to 45 percent, from 15 percent) for families with young children. These changes would have enormous implications for low-income families.

(Chart: Tax Policy Center)

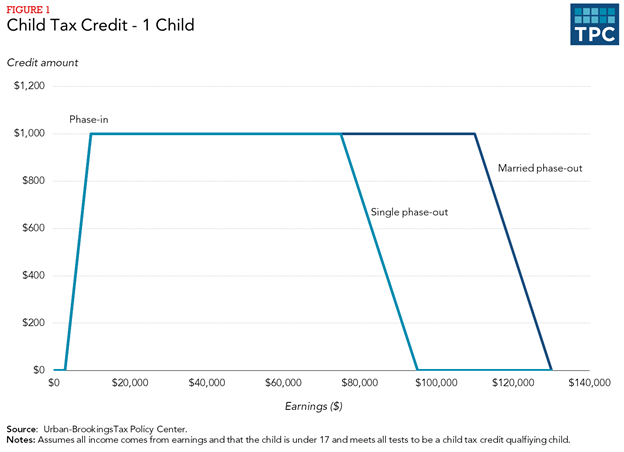

The chart to the left, from a paper released last week by Elaine Maag of the left-leaning Tax Policy Center, illustrates how the CTC works today. Basically, as the CTC is currently designed, families who earn less than $3,000 a year are not eligible for the credit. Once a family (with a child under the age of 17) hits that $3,000 threshold, they begin to receive the credit at a 15 percent phase-in rate, which means that, for every dollar of income the family earns, they receive a tax credit of 15 cents. The credit begins to phase out at $75,000 of earnings (for single parents), and $110,000 (for married couples), and it’s capped at $1,000 per child. The CTC is refundable, so families that owe less in taxes than the amount of their credit are eligible to receive a refund.

Under Clinton’s proposed changes, families could begin receiving the CTC with their very first dollar of earnings, and the higher phase-in rate means that families could receive the maximum value of the credit at a much lower level of earnings. Consider, for example, a single mother with two children under the age of five. To earn the full $2,000 CTC under the current rules, she would have to earn $16,333. Under a revised CTC, that same single mother would only need to earn $4,444 to receive a $2,000 credit, or $8,888.89 to receive the $4,000 credit. (For comparison, a person working a a minimum-wage job 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, earns $15,080.)

The real meat of Clinton’s plan has nothing to do with the middle class, and everything to do with the poor.

“Once you start phasing the CTC in at the first dollar of earnings, you’re able to direct benefits to the very lowest-income workers,” Maag says. “The proposed changes to the phase-in rate do the same thing — it allows very low-income families to have access to a higher credit.”

The changes that Clinton is proposing would make an enormous difference for poor working families in this country, many of whom do have some earnings but face significant barriers to the kind of full-time, well-paid employment that’s currently required to access the CTC. An analysis of Clinton’s proposals by the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates the changes would affect 14.2 million working families and “would lift about 1.5 million people (including about 400,000 children under age 5) above the poverty line and lift another 9.4 million people (including about 1.9 million children under age 5) closer to the poverty line.” The changes would also increase the incomes of another 5.2 million people (and 1.1 million young children) living in deep poverty.

Chuck Marr, the director of federal tax policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and a co-author of the analysis, says Clinton’s proposed changes are smartly targeted, as children under six have the highest poverty rates out of any demographic group.

“Young children tend to be the most responsive to interventions,” Marr says. “You can get a big bang for your buck.”

Though the plight of the deeply poor hasn’t received much attention in the general election, it emerged as a major issue during the primaries thanks in large part to Bernie Sanders, who repeatedly attacked Clinton over her support of her husband’s efforts to reform welfare in the 1990s.

“What welfare reform did, in my view, was to go after some of the weakest and most vulnerable people in this country,” Sanders said in February. “And, during that period, I spoke out against so-called welfare reform because I thought it was scapegoating people who were helpless, people who were very, very vulnerable. Secretary Clinton at that time had a very different position on welfare reform — strongly supported it and worked hard to round up votes for its passage.”

Sanders’ comments prompted a careful defense from former president Bill Clinton, who told the New York Times that the law did “far more good than harm,” but acknowledged that “the law needs to be changed to help the poorest of the poor.”

The welfare reforms of 1996 remain a politically contentious issue. Immediately after the law’s passage, policymakers on both sides of the aisle declared it a success. The labor force participation rates and earnings of low-income single mothers increased, and the child poverty rate declined.

In the intervening 20 years, however, two big problems with the law have emerged. The first is that welfare reform, with its time limits, work requirements, and intense focus on employment, seems to have left behind the most disadvantaged workers.

“What we’ve found is that welfare reform had some positive effects on household earnings and income, for those households headed by a single mom with some advanced education,” says James Ziliak, a poverty researcher at the University of Kentucky. “But the reform seemed to leave behind families whose mothers did not have a similar skill set. So if you’re prepared for the labor market, it seemed as though the combination of the [Earned Income Tax Credit] and the labor market and the reforms … collectively facilitated that transition from welfare to work. But for the less skilled, welfare reform seemed to leave those folks behind.”

The second problem with the reforms emerged when the economy started to go downhill. Programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit are great for families that are working, but they do nothing for unemployed families. And the substantial flexibility granted to states to administer the new welfare program resulted in many states simply gutting the cash assistance portion of the program and using the funds to plug budget holes elsewhere. In a summary paper on the topic, Ziliak noted that the majority of states actually had declines in their welfare rolls during the Great Recession. “The limited evidence to date suggests that [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families] did not respond to the Great Recession, and this lack of business-cycle response contributed to the growth of deep poverty,” he wrote.

There’s been increasingly widespread, bipartisan agreement that the welfare reforms of 1996 left some undesirable, unintended consequences. “None of us predicted that as many people would be dropped from the rolls as were dropped,” says Ron Haskins, a conservative economist who helped write the 1996 law and has also been vocal about some of its shortcomings. “And that includes conservative Republicans.”

The changes to the CTC that Clinton is proposing represent an effort to provide some assistance to the families who lost out in 1996. It’s not, however, entirely clear that expanding the CTC is the best means of helping the families that were left behind by welfare reform. Certainly, it would help poor working families, but it’s still a benefit that’s dependent on employment and earnings.

“I think a CTC of this magnitude would definitely get more moms into the economy — more moms would work,” Haskins says.

But perhaps the most interesting thing about Clinton’s proposal is that it might be more politically feasible than, for example, the kind of no-strings-attached “child allowance” that some European countries provide (and that some believe the United States should provide as well).

If, that is, Clinton’s plan (which the Tax Policy Center estimates at $209 billion) makes it through Congress first—something that Haskins, for one, finds unlikely. “There’s a set of Republicans who would support this,” he says. “But not at the level of hundreds of billions of dollars.”