A new op-ed reiterates Republicans’ calls for a new approach to poverty, but also focuses on a new metric.

By Dwyer Gunn

People register to receive free food in Richmond, California. (Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Earlier this week, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and Wisconsin Senator Ron Johnson co-authored an op-ed in USA Today calling for a new approach to poverty focused on homegrown solutions, community leaders, and a smaller role for federal government. The op-ed highlighted the work of the Joseph Project, a faith-based Wisconsin non-profit that provides basic job training and job-placement services to Milwaukee residents, as well as daily transportation to the nearby Sheboygan County, where more higher-wage jobs are available. Here’s what Ryan and Johnson had to say about how the federal government treats organizations like the Joseph Project:

But to expand opportunity, the federal government needs to stop competing with these social entrepreneurs.

Washington treats these entrepreneurs as it treats almost any successful enterprise — as a threat. Each year, it spends nearly $800 billion on more than 90 different programs to fight poverty, with almost no coordination or any consideration of an individual’s needs. It should be no surprise that upward mobility is no better now than when we started the War on Poverty in 1964. But it should be a scandal that today, if you were raised poor, you’re just as likely to stay poor as you were 50 years ago.

The op-ed goes on to highlight a three-pronged approach to fighting poverty: Reduce work disincentives in federal aid programs, allow states to combine federal aid funding streams and customize their programs, and require rigorous tracking of program results. There’s not much to get excited about here; it mostly just echoes the ideas laid out in the House Republicans’ “A Better Way” anti-poverty agenda. There is, however, one interesting twist: the focus on mobility, rather than poverty rates, as an indicator of a program’s effectiveness.

In the past, conservatives have cited the poverty rate when criticizing the effectiveness of the War on Poverty. In the official “Better Way” agenda, Ryan and his colleagues wrote that “the official poverty rate in 2014 (14.8%) was no better than it was in 1966 (14.7%), when many of these programs started.”

There are some big problems with that strategy. As Michael R. Fitzgeraldpointed out earlier this summer, using 1966 as a point of comparison is misleading, because poverty existed for centuries before that at astronomically higher rates that have never since been approached. If you extend the comparison back to 1959, the effectiveness of the social safety net starts to look a lot better, as this chart from a 2012 article by Dylan Matthews in the Washington Post illustrates:

(Chart: Washington Post)

Furthermore, the poverty rate often cited in these discussions, the “Official Poverty Measure,” doesn’t include income from safety net programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the Earned Income Tax Credit, or housing assistance. If you look at alternative poverty measures that do incorporate income from these types of programs, the picture starts to look a lot different.

(Chart: National Bureau of Economic Research)

One 2014 working paper that analyzed a different poverty measure (the supplemental poverty measure) offered some context on how government programs have affected the poverty rate.

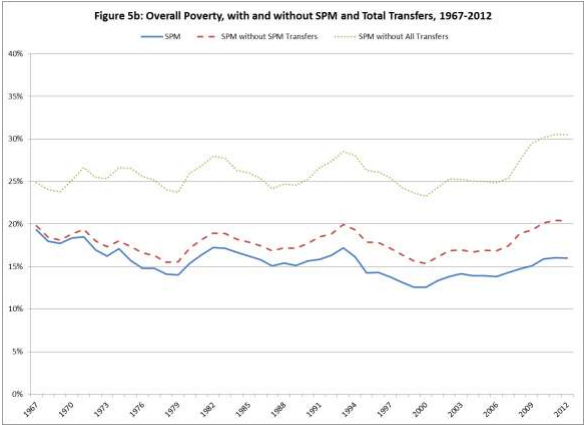

In the chart to the left, the dotted line illustrates what the poverty rate would have been without all government transfers, while the solid blue line illustrates the poverty rate after (some) government transfers are taken into account.

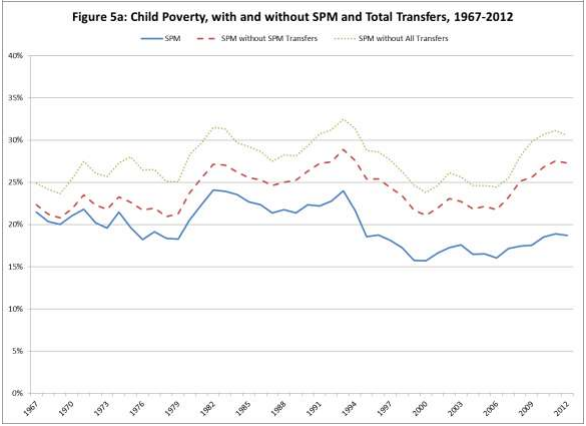

The role of government programs is particularly pronounced when you look at child poverty rates, as this chart illustrates:

(Chart: National Bureau of Economic Research)

Overall, the researchers estimated that, in the absence of government programs, poverty would have increased from 25 percent to 31 percent between 1967 and 2012. Instead, it’s fallen from 19 percent to 16 percent. And, in 2012, government programs reduced child poverty by 12 percentage points and deep child poverty by 11 percentage points. “Thus government programs today are cutting poverty nearly in half (from 31 percent to 16 percent) while in 1967 they cut poverty by only a quarter (from 25 percent to 19 percent),” the researchers concluded.

But in an ideal world, social safety net programs would do more than simply transfer enough money to low-income Americans to push their incomes above the poverty line. They would actually help poor and down-on-their-luck Americans become economically self-sufficient. They would increase that upward mobility that Ryan and Johnson talked about in yesterday’s op-ed. Such an outcome was, in fact, one of the major goals of the 1996 welfare reforms.

By this measure, Ryan and Johnson are correct that the War on Poverty has fallen short, which makes their pivot to focus on mobility interesting. Research by the economist Raj Chetty confirms that intergenerational mobility in the United States, which is low compared to other developed countries, has remained pretty much unchanged since the 1950s. And a new working paper by economists at the University of Kentucky suggests that the economic mobility of welfare recipients did not improve after the reforms of 1996, although other economic forces no doubt had plenty to do with that. As the Washington Post’s Max Ehrenfreund reports:

[I]n 1996, a woman who had grown up with welfare was 38 percentage points more likely to use public assistance than a woman whose mother had not received welfare. The most recent data, from 2012, showthat figure has increased to 44 percentage points.

An unfortunate consequence of our highly polarized political climate is that narratives around poverty and government spending tend to be reduced to simplistic terms: The War on Poverty is either an abysmal failure or a shining success that shouldn’t be questioned. The federal government is either spitefully crowding out social entrepreneurs or it’s the only institution capable of effectively lifting people out of poverty.

Of course, the last 50 years have been characterized by economic forces that have hollowed out the middle class, resulting in wage stagnation and rising inequality. We don’t know what would have happened to economic mobility in the absence of government spending. Perhaps, sans programs like the EITC, it would have worsened.

But the real truth about the War on Poverty is that it’s complicated and nuanced. Programs like SNAP, the EITC, housing vouchers, and Medicaid do a lot to ensure that low-income people in this country, especially children, have enough food to eat, a roof over their heads, and access to medical care—all outcomes that most people would agree are associated with improved long-term outlooks for children.

But it is also true that our country — our schools, our politicians, our social safety net, and our government — is not doing enough to improve intergenerational economic mobility, and to give children born in poverty a shot at a better life. That doesn’t mean we should stop spending money on safety net programs, but it does mean we should work to improve them, and consider solutions from across the political spectrum in pursuit of that goal.