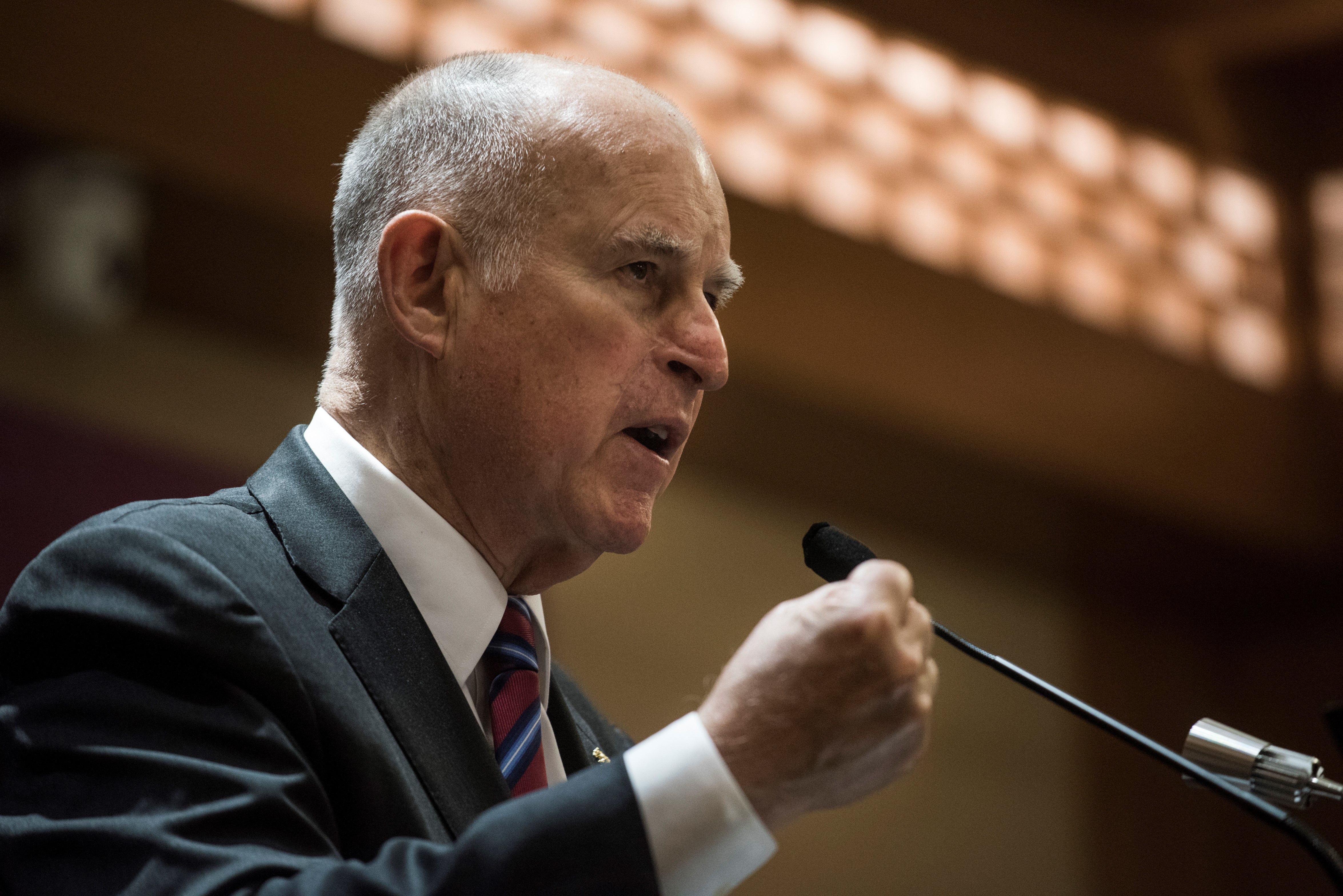

Following a month-long summer recess, the California legislature has reconvened this week, and no issue is more top of mind than affordable housing. There’s a tragic irony there: In trying to come up with a plan to address the state’s housing shortage, Governor Jerry Brown and the other lawmakers are working to fix a problem that Sacramento actually helped create in an effort to balance the state budget six years ago.

In the wake of the Great Recession, the state’s finances went into the tank, with budget deficits as large as $27 billion. Brown was elected in November of 2010 on a promise to help solve California’s fiscal woes. He accomplished that through a combination of state budget cuts and tax increases on upper-income earners, eventually bringing the books into balance. But one of those cuts, the 2011 move to eliminate the state’s re-development agencies, wiped out billions in revenues that were earmarked for affordable housing.

Since 2012, the elimination of re-development has meant about $6 billion less for affordable housing. The money instead has been used to help counties offset rising Medicaid costs, and to fund local schools, while helping the state reduce its obligations to backfill local governments.

“Eliminating re-development didn’t cause the housing crisis, but it certainly has made our problems worse.”

Removing re-development funds did not by itself cause California’s housing crisis. Local resistance to new development and environmental restrictions on new building have also been contributing factors. But the 2011 vote to eliminate funding did add to the state’s current woes, says Larry Kosmont, a Manhattan Beach-based real estate and economic adviser to cities and developers.

“That was a source of money that could be used to help build new units or could also be used to subsidize rents directly,” he says. “Eliminating re-development didn’t cause the housing crisis, but it certainly has made our problems worse.”

The re-development program was far from perfect. Though it siphoned off a portion of property tax revenues to be used for housing and other projects, many cities simply didn’t want to build more inventory. The same NIMBY concerns that have derailed other proposed solutions to the state’s housing crisis also led to re-development money going unused, or being spent by cities looking for ways for ways to get out of their obligation to build more housing.

“Many agencies didn’t want to do affordable housing, so they spent money hiring consultants and lawyers to not do hard-target affordable housing,” Kosmont says.

But other cities really did utilize the re-development program, he says—and with good results. That money dried up just as it was needed most, as the state’s economic recovery took hold, its population grew and local resistance to new development persisted. The end result is a housing riddle that will not be easily solved.

The median price of a home in the state has topped $500,000—about twice the national average. Home ownership rates are the lowest they have been since World War II. More than 1.5 million households spend more than half of their income on rent, which is among the highest in the country, according to the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development.

Now, with less than a month before the end of the legislative year, Sacramento lawmakers are working to find a way to help restore some of the money that was diverted back in 2011. The linchpin is a general obligation bond that would have to be approved by voters, and could set aside anywhere from $6-$9 billion to help ease the state’s housing shortage.

(Photo: Fred Dufour/AFP/Getty Images)

Even if a bond is approved, it won’t solve the entire problem. The money would be enough to subsidize anywhere from 25,000 to 40,000 housing units statewide—a fraction of the state’s current shortfall. Ultimately, California’s ability to solve its housing crisis won’t just be finding the money to build new housing, but also building the political will and local support to actually spend the money that is being set aside to help low- and middle-income people find ways to keep up with soaring housing costs.

While Democrats are focusing on raising new revenues to bring in more housing, Republicans are focusing of regulatory reform to make it easier to build new homes and remove local barriers to home construction.

Some Democrats are joining that call for regulatory reform. One bill, by San Francisco Democrat Scott Weiner, “creates a streamlined, ministerial approval process for development proponents of multi-family housing if the development meets specified requirements and the local government in which the development is located has not produced enough housing units to meet its regional housing needs assessment.”

That’s similar to a proposal that was put forward by Brown last year. Democrats in the legislature rejected the plan amid strong opposition from environmental and labor groups.

These next three weeks will test whether the housing crisis has gotten bad enough for Democrats to abandon some of their core constituencies in an effort to help bring the state’s high home prices and rents under control.