The dramatic growth in the number of school districts pursuing socioeconomic diversity is good news. Research suggests there are considerable academic benefits, but integration also reduces juvenile crime in at-risk neighborhoods.

By Aaron Loewenberg

(Photo: Ian Waldie/Getty Images)

A federal judge ruled that the Boston School Committee had deliberately segregated the city’s public schools by race. To remedy this constitutional violation, the judge ordered about 18,000 black and white students to take buses to schools outside of their neighborhoods. The backlash to this plan was swift: White parents threw bricks and stones as the buses arrived and refused to let their children board. The violent riots that later occurred led some reporters to describe the city as “a war zone.” The mayhem unleashed in Boston would serve as a cautionary tale for advocates of any sort of mandatory school integration plan.

That was in the summer of 1974. Since then, severalstudies have suggested that integrating schools by race and income is one of the most effective ways to boost student achievement. A 2010 meta-analysis of 59 different studies found that students of all races and income levels are more likely to have higher math outcomes when they attend racially and socioeconomically diverse schools. The researchers concluded that the academic benefits of diverse schools are “consistent and unambiguous.” There is, in fact, a large body of evidence suggesting that diverse schools benefit not only low-income students, but also their middle- and upper-class peers. Other research has found that pre-kindergarten students who are part of socioeconomically diverse classrooms are likely to learn more, particularly in the areas of receptive and expressive language and math. And a separate study of elementary school students in Montgomery County, Maryland, found that children in public housing who were assigned to attend low-poverty schools were able to cut the achievement gap between themselves and their more affluent peers in half by the end of elementary school.

With so much research extolling the benefits of integration, education advocates were pleased that President Barack Obama’s last budget request included a new $120 million “Stronger Together” grant program to support local efforts to integrate schools by income. The proposed program would encourage the development of innovative local plans to increase socioeconomic diversity through voluntary, community-led efforts. If enacted, this grant program would more than double federal funding of efforts to encourage school integration, which up to now has consisted solely of a single $100 million program designed to help high-quality magnet schools implement desegregation plans.

Those focused on integration by income rather than race are less likely to stir up the kind of white backlash witnessed during the forced busing era of the 1970s.

The president’s proposal is good news. Statistics tell us that America’s public schools are more racially segregated now than they were in the 1970s. But why does Obama’s plan target integration by income rather than race? There are two reasons for this, one constitutional and the other political. On one of these fronts there is reason for optimism that subsequent developments might make it easier in the future to implement integration plans explicitly targeting race.

First, the constitutional front: In 2007, in a split 4–1–4 decision, the Supreme Court struck down racial integration plans in Louisville and Seattle, claiming that the plans violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution because they “do not provide for a meaningful individualized review of applicants,” but instead rely on racial classifications in a “nonindividualized, mechanical way.” Income integration plans, on the other hand, are completely legal because, according to case law, income classifications don’t trigger strict scrutiny from courts the same way racial classifications do, since income, unlike race, isn’t a suspect classification. But with the death of Antonin Scalia throwing the Court’s ideological balance into question, it’s possible that a future Court might be more amenable to racial integration plans.

Then, of course, there are the politics of the plans. Those focused on integration by income rather than race are less likely to stir up the kind of white backlash witnessed during the forced busing era of the 1970s in places like Boston and Richmond. Plans that focus on integration by income could offer students from low-income families of all races the opportunity to attend high-quality schools, increasing the likelihood of support that spans multiple demographics.

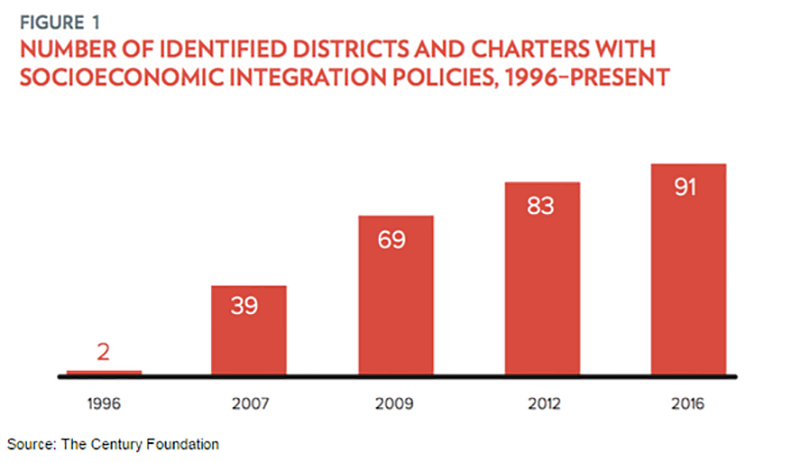

Aside from Obama’s proposal to more than double federal spending on school integration efforts, a new report from the Century Foundation offers evidence that socioeconomic integration of schools is already taking place in parts of the country. In fact, the report points out that there are currently 91 districts and charter networks in 32 states that use socioeconomic status as a factor in student assignment. This represents a significant increase in the last 20 years in school districts utilizing some sort of socioeconomic integration plan (see chart below). These districts and charter networks with socioeconomic integration policies now enroll over four million students, about 8 percent of all public school students.

Most of the integration strategies utilized by these districts fall into five main categories. The most common strategy used is re-drawing school attendance zone boundaries in an effort to increase socioeconomic balance. The other main approach used is adoption of a choice-based policy that specifically aims for greater income diversity. After families rank their top school choices, students are assigned to schools based on both their preferences and an algorithm designed to ensure a fairly even distribution of students by socioeconomic status across schools. Some districts with integration policies also utilize magnet schools and charter schools that specifically consider socioeconomic diversity in admissions. Finally, some districts have transfer policies that give preference to transfer requests that would increase school socioeconomic diversity.

Of course, integrating schools by income is not the same as explicitly attempting to bring about greater racial diversity in our nation’s schools, but research suggests that socioeconomic integration plans can be effective in reducing racial segregation since socioeconomic and racial segregation often overlap. In Wake County, North Carolina, for example, the school district was forced to stop using race-based assignment plans due to court resistance in the late 1990s. When they replaced these plans with new income integration plans schools did become slightly more segregated than before, but not nearly as much as those districts that dropped racial integration plans and replaced them with no integration plan at all.

The dramatic growth in the number of districts pursuing socioeconomic diversity is good news, and not only because of the academic benefits of integration mentioned earlier. New research suggests that increasing socioeconomic diversity in schools might actually help reduce juvenile crime in at-risk neighborhoods. Researchers linked school data and police arrest records in Charlotte and found that concentrations of previously arrested students living within about half a mile of each other don’t increase crime rates in the area unless the students attend the same school. The researchers conclude that “school segregation itself may be partially responsible for high crime rates in disadvantaged urban areas” and that crime could be reduced by efforts “to manipulate the location or school assignment of youth across settings.” In other words, implementing policies that achieve a more even mix of income levels in school districts could not only increase academic achievement but might also reduce levels of juvenile crime.

Of course, despite the evidence pointing to the multiple benefits of more diverse schools, it’s quite possible that Obama’s proposed grant program will not become a reality any time soon. But even if this specific grant program never materializes, the president’s request, combined with the growing number of school districts unapologetically pursuing socioeconomic integration plans, suggests that, for the first time in decades, school integration might just have some momentum.

||

This story originally appeared in New America’s digital magazine, New America Weekly, a Pacific Standard partner site. Sign up to get New America Weekly delivered to your inbox, and follow @NewAmerica on Twitter.