Many people envision the typical child with ADHD as rambunctious, unable to sit still, disruptive in class, and incapable of paying sustained attention to one task. And a new study in the New England Journal of Medicine has found that the youngest children in a class are more often diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—potentially because their developmentally typical distraction and impatience stand out against peers who are nearly a calendar year older.

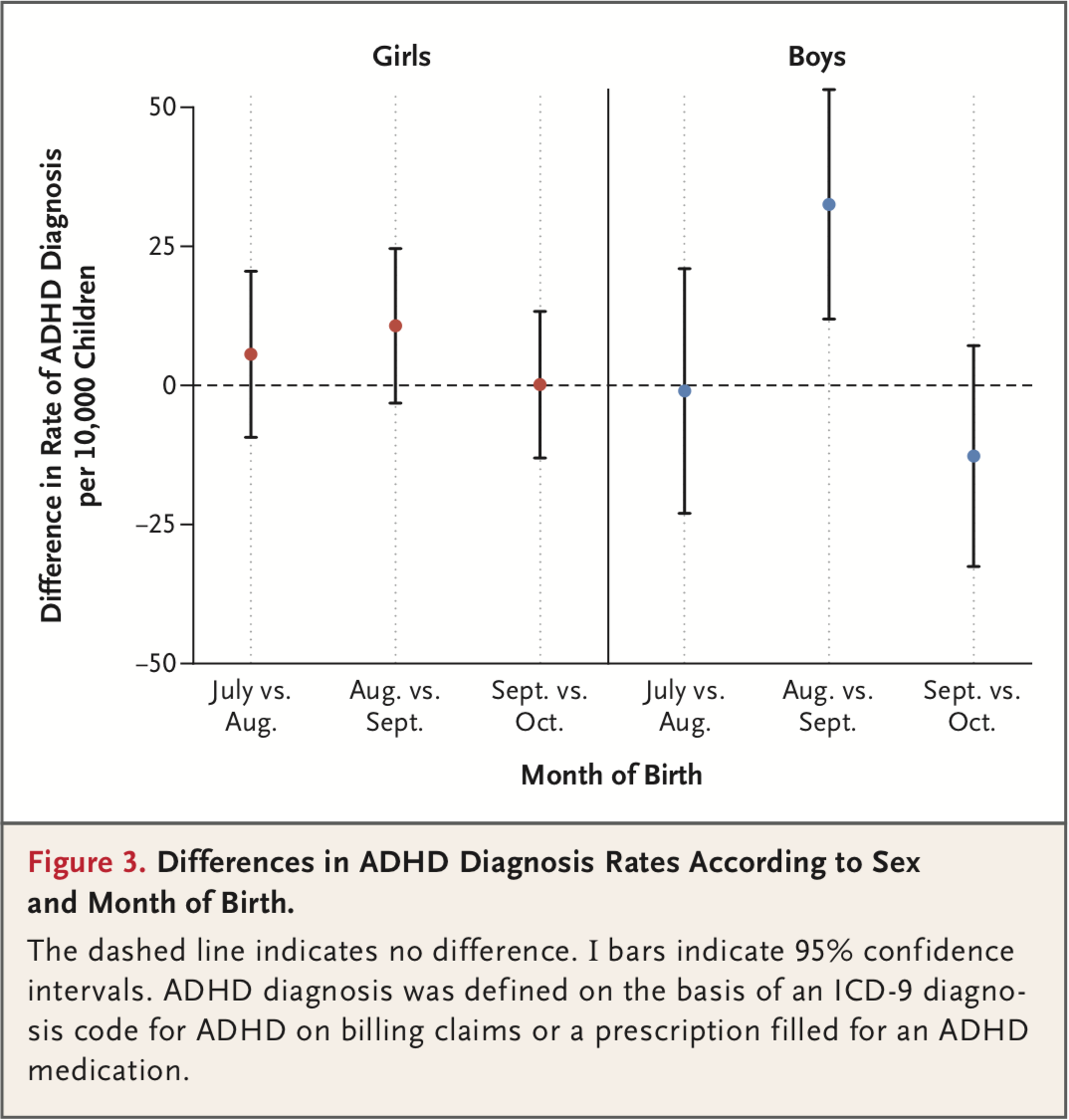

That’s because the tasks and behaviors younger children have more trouble with—sustained attention, fine motor skills, emotional regulation, and sitting still, among others—are also classic deficits for children with ADHD. But that symptom profile doesn’t fit all children with the disorder: It’s based on researching boys with the condition. Girls with ADHD tend to display a different, and often overlooked, set of symptoms. And unsurprisingly, in the study, the disparity of diagnoses of ADHD in children born in August versus September is only significant in boys.

The study cuts to the heart of the “academic redshirting” debate—a term for holding children back from kindergarten until they’re older and supposedly more likely to succeed. Many United States schools use an arbitrary birthday cutoff date of September 1st for children entering kindergarten, which can mean that children born in September enter school with children born almost a calendar year after them in August. While educational outcomes tend to even out over time, the differences are especially stark in children who have just begun attending school. The impulse control, attention spans, and even motor skills of a seven-year-old can be very different from those of a six-year-old. So in a given classroom, the youngest children may be displaying developmentally typical inattentive or fidgeting behavior. But when compared with peers who are many months older, that behavior is more noticeable—and can be attributed to ADHD instead of age, the authors suggest.

The study draws on diagnoses of children born between 2007 and 2009 in a large insurance database, so the authors don’t have access to what factors influenced any child’s diagnosis and treatment—or whether the children are incorrectly diagnosed at all. But they describe how many children are first referred for ADHD testing by parents or teachers, who observe the child in a setting among their peers, instead of by physicians, who typically see the child alone.

However, the authors spend much less time on the sex disparity, both in the paper and their popular New York Times opinion piece. While Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data shows that 15 percent of school-aged boys are diagnosed with ADHD, as opposed to 7 percent of girls, in adulthood, that changes. The condition is recognized in more women, who are often diagnosed when they seek treatment for other problems like depression or anxiety, and diagnoses become more balanced between sexes. And it’s a lifelong issue, which suggests many young girls are slipping through the cracks.

In the study, the rate of ADHD diagnoses for boys born in August was 53.2 boys out of every 10,000. Only 11.9 out of every 10,000 boys born in September had the same diagnosis—a difference of 32.5. But for girls, the difference was only 10.7 out of 10,000 children; the authors called that finding not significant.

Studies have shown for decades that girls are under-diagnosed with ADHD—mostly because their manifestations of the condition are often different from boys’. They can be incredibly bright but struggle in school. They can hyper-focus on tasks, reading a book in one sitting, but be unable to finish homework on time. They might have plenty of friends but struggle reading social cues or listening to peers.

And gendered socialization plays a role too: The pressure on girls to be socially acceptable people-pleasers teaches many of them to cope with their deficits in planning, function, and focus earlier than boys, who often have leeway to be hyperactive and physical for longer. A young girl’s jumping between tasks and chattiness with peers might look like ditziness or gregariousness instead of the disruptive or impulsive behavior teachers are looking for. Boys who interrupt class, break things, or accidentally hurt themselves are more pressing challenges for parents and teachers; a girl’s inability to organize, constant tardiness, and forgetfulness can be missed more easily.

While there’s rising debate about over-diagnosis and the risks of stimulants, missing a diagnosis has serious consequences. ADHD often occurs next to a whole host of other mental-health issues, like anxiety and depression. The impulsivity related to the disorder can lead people to make poor choices, have risky sex, or abuse substances. Emotional issues and poor emotional regulation are common symptoms, especially in adulthood. And people who go untreated often internalize the message that they’re “lazy,” not trying hard enough to complete tasks, or choosing not to stay organized. The study’s greatest impact might not be on redshirting at all: It could be a reminder to teachers, parents, and doctors that not all ADHD looks the same.