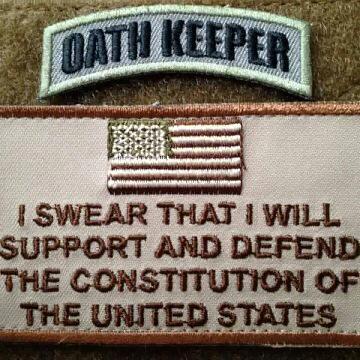

As gunfire and tear gas marked the first anniversary of the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, authorities in fear of the same rioting and looting that marred otherwise peaceful protests last year, recently declared yet another state of emergency. Amid all the clashes between protesters and law enforcement, a group of heavily armed gunmen once again rode into town. Bearing assault rifles and outfitted in gas masks and camouflage, the men came to Ferguson for one reason: to “defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic.”

The Oath Keepers, the 35,000-member-strong paramilitary “patriot” group of former police officers and first responders, had come to Ferguson during the first outbreak of rioting in 2014. Patrolling the rooftops of the city’s bustling downtown, the Oath Keepers claimed to be protecting private property from arson. The organization claims it’s constitutionally empowered to protect “the best part of America, the creative part, the small businesses, the hardest working people in the United States of America … from arson” as one member told ABC News in 2014.

Why is it that white Americans carry high-powered weapons openly in the name of “property,” while African Americans constantly risk the full wrath of state power for virtually no reason?

But something’s not right. Stewart Rhodes, who founded the group in 2009, has explicitly warned of a coming “race war” orchestrated by Comrade Obama, a common trope for anti-government, militaristic patriot groups. Even more maddeningly, despite St. Louis County Police Chief Jon Belmar’s condemnation of the Oath Keepers’ arrival in Ferguson last month, calling the group “unnecessary and inflammatory,” they’ve somehow managed to roam the streets of Ferguson unmolested by local law enforcement—all while locals are teargassed and reporters arrested. For many, this is a sure sign of structural racism in the U.S. After all, why is it that white Americans carry high-powered weapons openly in the name of “property,” while African Americans constantly risk the full wrath of state power for virtually no reason?

Vigilantism, the enforcement of justice in the face of government failure, was enshrined in our national mythos long before it became the domain of pop-culture heroes like Dirty Harry and Batman, a noble cause on par with the “right to revolution” and popular sovereignty in American legal lore. But what originally began as a legitimate defense of property necessitated by the lawlessness of the 19th-century American frontier has since morphed into a cover for intimidation and terror.

First, a brief history lesson. Between the close of the Revolutionary War and the gold rush of the 1850s, the federal government became the owner of 1.4 billion new acres of land. Despite a lack of infrastructure and regular policing outside of territorial courts and peace officers, federal land policy was designed to parcel out land quickly to settlers in order to allow private operators to exploit the natural rewards of the massive frontier. The result was, well, the “wild” West. But in reality, the West wasn’t that wild: Groups of settlers banded together to form mutual protection agencies (MPAs) to define and enforce their property rights, ranging from the claims clubs and cattlemen’s associations that divvied up the farmlands of the Great Plains, and the mining camps that came to dot ore-rich California. These MPAs are an anarcho-capitalist dream, the closest historical representation of the immaculate conception of a minarchist regime in a Lockean “state of nature.”

What originally began as a legitimate defense of property necessitated by the lawlessness of the 19th-century American frontier has since morphed into a cover for intimidation and terror.

Vigilantism’s first iteration seemed no different than the mutual protection agencies. As I’ve written before, the first true vigilance committee emerged in 1851, in response to the specter of arson and murder in San Francisco following an influx of fortune-seekers two years prior. It was local importer Samuel Brannan who rallied hundreds of citizens into a Committee of Vigilance to protect their property when conventional law enforcement couldn’t, driving the marauders from town. Sure, the vigilantes weren’t organized the same way as the ad-hoc organs of law enforcement that already dotted the frontier—they took no votes, followed no bylaws, and lacked the formal economic and legal agreement that provided the institutional core of MPAS—but on paper, it is the purest institutional forebear to the Oath Keepers: a voluntary group of concerned citizens standing up against the threat of violence and destruction.

But American vigilantism quickly morphed into something more sinister. Despite significantly lower crime rates in 1856, journalist James King used San Francisco’s Daily Evening Bulletin to whip the city into a “near-panic psychology,” giving the newly reformed Committee of Vigilance cover to rally some 6,000 furious citizens to oust the Democratic Party that ruled the city and, a few years later, install their Republican allies in what was essentially a coup. King’s murder at the hands of a political operative may have sparked the uprising, but his death also effectively dislodged the public and private sector elites he so despised. “Property” was essentially a cover for a political grudge. This would become a regular trend: A few decades later, Montana journalist Robert Fisk would use the Helena Daily Herald in 1879 to warn of a “coterie of petty offenders” and “the horde on our borders” to create a public perception of lawlessness despite similarly low crime rates.

Vigilantism was once a natural reaction to property rights, but unlike the mutual protection agencies built on transparency and consent, the most popular versions in California and Montana functioned as organs of norm enforcement rather than law enforcement, engines of abstract “justice” rather than pure property, subject to the whims of a few elites with social clout. This is the legacy of the 1856 Committee of Vigilance in San Francisco and the vigilantes of Montana: Like the humans that comprise them, they are deeply corrupt and deeply skewed organizations, protected and tolerated within those inviolable American principles of life, liberty, and property.

Vigilantism is fundamentally based on the skewed interpretation of a handful of angry men.

The Oath Keepers want to channel the vigilantes of old in their quest to protect property and uphold the law. Ironically, they actually succeed, but in the worst possible way: By using “property,” the sacrosanct norm of American civic life, as a cover for terror and intimidation along sociopolitical lines. But by speaking the language of “property” and “property rights,” the Oath Keepers and other patriot groups manage to operate with apparent ease, and open carry movements flourish across the country with apparent deference from police officers and lawmakers. All the while, the national media gravitates toward isolated outbreaks of black violence amid otherwise peaceful demonstrations of solidarity. It’s this impulse, this understanding of our implicit American values, that explains why the Black Panthers scare Americans to death, but the Oath Keepers somehow don’t. In practice, vigilantism is an inherently conservative impulse, and it inherently benefits those seeking the status quo.

In the wake of a year-long national conversation about the relationship between law enforcement and African Americans, the presence and tolerance of the Oath Keepers is as much a rebuke to the #BlackLivesMatter movement as it is a disquieting specter of future violence. Consider this: While Montana and California hosted local vigilante groups, they laid the groundwork for a national organization to emerge after the Civil War to protect the status quo. It was called the Klu Klux Klan.

The Oath Keepers rode into Ferguson to ostensibly protect property—to “defend the Constitution”—but the trouble with vigilantism is, like everything else on the planet, it’s fundamentally based on the skewed interpretation of a handful of angry men. While we love our Dirty Harrys and our Batmans, they are little more than social bandits, terrorist who fight bad guys, a few generation of firearms and body armor removed from the pitchforks and torches of the American frontier. Modern vigilantes like the Oath Keepers aren’t just “unnecessary and inflammatory” in Ferguson; they’re inherently flawed. If the Oath Keepers are really in Ferguson to defend the Constitution, there’s only one good thing they can do: Leave.