I went to see The Secret Life of Pets to support the basset hound. I came away mad about the wretched, unnecessary gender inequality in animal cartoons.

By Steph Cha

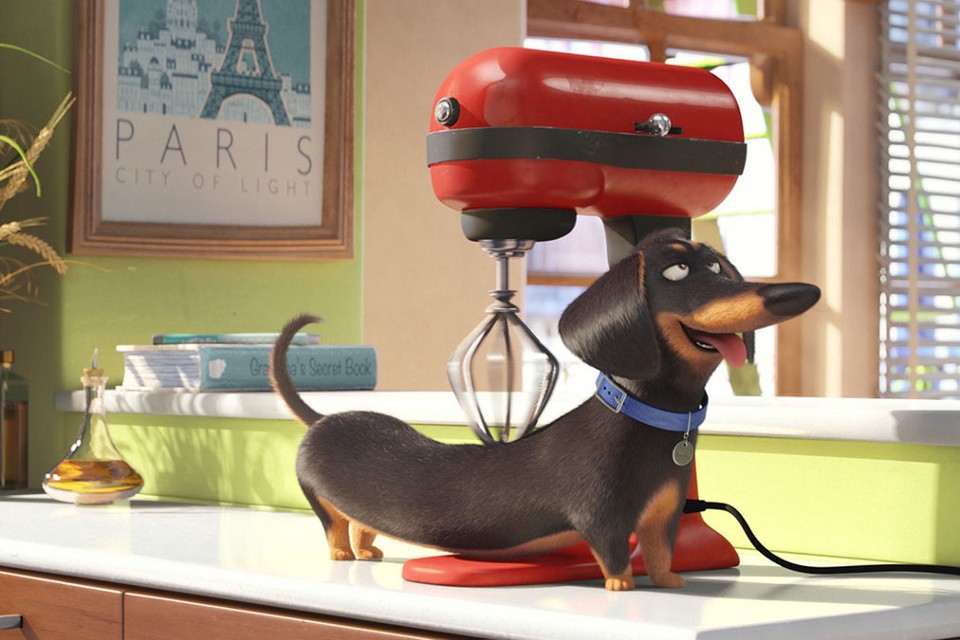

Duke is a good boy. He’s also over-represented in film. (Photo: Universal Studios)

If you’ve seen any movies not specifically aimed at chicks, you’ve probably noticed that men are just a bit over-represented in film. Some of this gap is easy enough to explain — historically, women have been excluded from cinematic arenas like war and politics and seafaring, and there are whole genres that skate by with male-dominated ensemble casts, the token roles reserved for femme fatale eye candy.

Thankfully, there are plenty of genres where there is literally no reason why male characters would outnumber female characters. One of these is the wonderful category of cartoons, the medium through which so many innocent, impressionable children learn about the ways of the world. Many of these animated movies concern humans, and, inevitably, human stories — or at least the ones mainstream films choose to tell — skew toward the male heroic.

But wait — what about these cartoon animals? Why in tarnation are all of them boys?

Garfield, Clifford, Curious George; Tom and Jerry; Spongebob and Patrick; every named rat in Ratatouille. Even the Minions are all boys — not animals, I guess, but little yellow Tic-Tac creatures I never thought of as gendered until they were named Kevin, Stuart, and Bob — as confirmed by their creator Pierre Coffin (“Seeing how dumb and stupid they often are, I just couldn’t imagine Minions being girls,” he said, in his bid for Benevolent Sexist of the Year).

I can’t help but think that the boys who watch these movies grow up to be the men who feel dominated and threatened by any attempts at clawing back some gender parity. Look how they cried over an all-female Ghostbusters.

Of course, there are girl animals in these films, too, but it sure seems like the default is boy until there’s a compelling reason to switch to girl — the romantic counterpart being the most common example, which accounts for the Minnie Mouses and Nalas of the cartoon world.

There are salient exceptions, I recognize — please don’t email me about Zootopia, a movie so notably progressive that it’s inspired rage-filled think pieces on the right about politically correct filmmakers brainwashing the youth (and which, for the record, was originally supposed to star Nick, with Judy as his sidekick). This is the nature of messaging — it tends to raise eyebrows when it deviates from the standard script, even when the standard script is toxic bullshit. I’ve seen far less outcry about The Secret Life of Pets, the new movie by Illumination Entertainment — the company behind Despicable Me and Minions — whose messaging is less explicit but far more pernicious in its thoughtless reinforcement of gender inequality.

I knew I was going to pay money to watch The Secret Life of Pets as soon as I saw the droopy eyes of a basset hound peering at me from a billboard. (As a proud basset mom, I believe basset hounds are scandalously underrepresented in film, and wanted to make sure I went and supported this fine basset hound actor in his feature debut.) As it turns out, I found the basset character, Pops, under-used and not quite basset-y enough in personality (he wasn’t dopey and showed a lot of initiative), though I applaud the scene in which he trips on his ears. The movie was otherwise enjoyable, a short, cute animated romp about New York City pets getting in and out of trouble. The kids in the theater loved it. There were a couple of poop jokes, which made them all lose their minds.

(Photo: Universal Studios)

But my takeaway, because I am a fed-up feminist, is that here is another movie with a huge ensemble cast dominated by male characters — and for no good reason. As A.O. Scott writes in his New York Times review, “Representation matters.” Of course, Scott is referring to the lack of cats in the movie, whereas I’m wondering why, out of over a dozen named animals in the cast, only two are portrayed as female — Chloe the cat and Gidget the fluffy white lapdog. Sweetpea, the bird, is never gendered, but all the others — including both lead dogs, a hawk, a guinea pig, and a bunny — are explicitly male. (At least movies about animals aren’t usually racist — except, oh right, Dumbo; and Illumination’s next movie, Sing, features an ensemble cast of animals, including a criminal gang made up of, dear God, gorillas. But that’s a whole separate think piece.)

This just feels so warped. Roughly half of all animals are female, and many species — including most of the ones represented in this movie — show almost no difference in secondary sex characteristics. Dogs come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes and personalities, but these are determined, for the most part, by breed, not by sex. Half of all bulldogs and Tibetan mastiffs are female, just as half of all Pomeranians and Yorkies are male. Dogs do not conform to our gender stereotypes: They’re just dogs. Since there’s no genitalia displayed in the movie, Max and Duke could have been Maxine and Duchess without changing anything but their names. Even the voices could’ve stayed the same (though, woof, let’s not even get into what these gender disparities mean for working actors) — I’ve never known a Newfoundland to bark in soprano.

Dogs come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes and personalities, but these are determined, for the most part, by breed, not by sex.

I can’t conceive an explanation for this gender breakdown that doesn’t boil down to sheer laziness and generic thinking, an unwillingness to play with default settings. It’s telling that Gidget, the sole girl dog, is not only small and fluffy, but also a love interest for Max — she has to be a girl, and that’s why she isn’t a boy. The Jack Russell, the Newfoundland, the dachshund, the pug, the basset — there’s no reason they can’t be boys, so there they all are: a statistically unlikely cluster of male dogs.

Some industry-watchers might argue that movies with male leads just sell better, since little boys think that movies with girl leads are yucky and won’t get into their cars and hand over their credit cards to see them. Let’s say this is true — whose fault is that? Could it be that boys are so used to seeing boys everywhere that they start to think boy cats and boy dogs are normal, and that girl cats and girl dogs somehow strain acceptable bounds of credibility?

(Photo: Universal Studios)

I once helped out with a field trip put on by 826LA, an educational non-profit with a focus on creative writing. This field trip was for a class of local kindergartners, who used their kindergartner brainpower to come up with a story. The first thing they had to do was to come up with a main character as a group. The volunteer leading the brainstorm asked them to vote on whether it should be a boy or a girl. Boy won. The volunteer later told me boy always won, because while girls sometimes voted boy, boys never voted girl. These kids were five and six years old, but they’d already gotten the message — that male is default, female other; that stories about boys are more interesting and important.

This wasn’t their fault, of course. They were just adorable children who’d grown up consuming media in which even mice and Minions are boys. But I can’t help but think that the boys who watch these movies grow up to be the men who feel dominated and threatened by any attempts at clawing back some gender parity. Look how they cried over an all-female Ghostbusters.

Because the Zootopia alarmists are right about one thing — children are both attentive and malleable, and when they’re told how the world works, they tend to remember. They have plenty of time to absorb the rules of the patriarchy — whole theaters full of child moviegoers have a slew of male-dominated grown-up movies to look forward to, not to mention their history books and the entire English canon. It’s a sorry waste when their magical talking animal cartoons tell the same tired, old story.

||