A few weeks ago, Colorado’s state legislature wrapped up its 2017 session. As I noted here, this was one for the record books—it saw a great deal of productivity in a chamber that recently became the most polarized state legislature in the country. Is there a lesson in here for other legislatures, especially the United States Congress?

We tend to think of polarization and productivity as operating at cross purposes. That is, a highly polarized legislature will be prone to gridlock, where neither party is willing to allow the sort of compromises often necessary for governing. Conversely, a depolarized legislature should be more productive, as members from either party are more open to arguments from the other side and face fewer costs for brokering compromises.

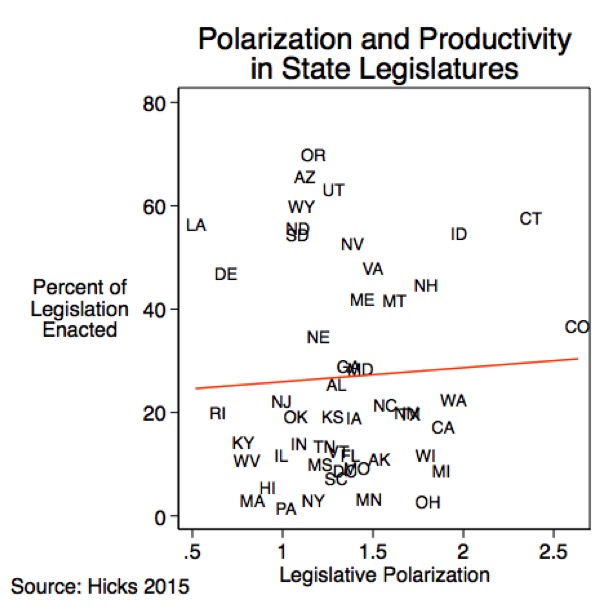

Yet it turns out that the relationship between polarization and productivity isn’t quite so simple. In the graph below, I’ve used a measure of legislative polarization in state legislatures on the horizontal axis, and a measure of legislative productivity (the number of bills enacted divided by the number of bills introduced) on the vertical axis. This latter measure is far from perfect, as there’s all sorts of variation in the way legislatures process bills. But it gives us a general idea of just how effective a chamber is in processing legislation.

As the chart shows, there’s basically no relationship between polarization and productivity. Polarized legislatures like Washington and California aren’t very productive, while another polarized one like Connecticut is. Colorado falls around the middle in terms of productivity.

Political scientist William Hicks wrote on this subject recently at American Politics Research in his article “Partisan Competition and the Efficiency of Lawmaking in American State Legislatures.” (This paper is the source of the data for my graph above.)

Hicks found that legislative productivity is contingent on several different factors related to polarization. For one thing, if there’s a close margin in the number of seats between the majority and minority parties, polarization will tend to undermine productivity, while more disciplined parties can actually bolster productivity in a more lopsided chamber. For another, divided partisan control of government can undermine productivity, especially in a legislature that’s nearly evenly split between the parties’ seat shares.

Hicks’ findings make Colorado’s example seem all the more extraordinary. It is, after all, a divided state government, with Democrats controlling the House and Republicans the Senate, and the governor being a Democrat. It is also a legislature where the seat balance between the parties is fairly narrow. House Democrats have a 37–28 seat margin, while Republicans have only a one-seat margin in the Senate. All these features tend to work against legislative productivity.

And indeed, the Colorado statehouse has not always been so productive. In last year’s session, it proved unable to address many pressing state issues. This year’s productive session appears to be the product of some creative chamber leaders who knew what their caucuses could and couldn’t accept and were eager to demonstrate they could get some work done.

Hicks’ research doesn’t speak very highly for the current national government, meanwhile, which currently enjoys unified party control, isn’t as polarized as many state legislatures, yet still can’t get all that much done. There may be some particular dysfunction operating at the national level that just doesn’t apply to the state level.