In 2010, Vice President Joe Biden introduced the president in the East Room of the White House just before the health care reform bill was signed into law. As Obama took his position behind the lectern, Biden leaned into his ear. “This is a big fucking deal,” the vice president whispered, without realizing his mic would broadcast the unpleasantry out to the free world. He grinned furtively and stepped aside.

Though the raffish utterance seems more suitable for the mouth of a rabble-rousing sailor than the esteemed tongue of the man second-in-line to the presidency, recent research indicates that it won’t hurt his prospects in 2016.

A new study in the Journal of Language and Social Psychology suggests this kind of crass commentary shouldn’t be constrained to whispers in the halls of power. If delivered with some degree of grace, vulgarity can actually work well as a rhetorical device on the campaign trail. The linguistic quirks seem to heighten the perception of a candidate as a more informal “everyman,” who the voter evaluates more positively and is even more likely to vote for.

“Often political language is perceived as hard and politicians are seen as far from common people and this is one of the reasons [for] the negative evaluation of them,” lead author Nicoletta Cavazza explains in an email. “We think that informality in political language makes the audience feel close to that politician, because vulgarity is widespread and particularly associated to friendly conversations and contexts.”

In an experiment, the researchers told 110 Italians to imagine that there was an upcoming local election. Then, they asked them to read a blog post about unemployment penned by a candidate. The experimental post contained the phrases “a situation that pissed off everyone” and “is up shit creek,” whereas the control condition referenced “a situation that worries everyone” and “is in a tragic situation.”

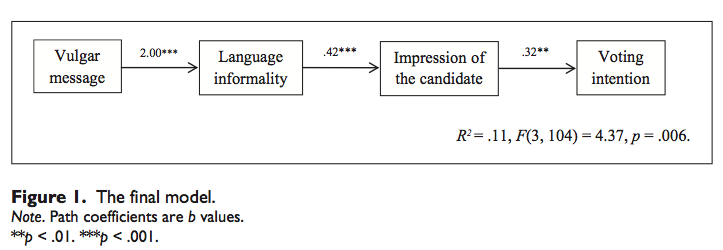

Naturally, the vulgar condition was rated “as more informal than the control message.” The informal language rating also led to a better evaluation of the post’s author and a higher likelihood that the subject would vote for the candidate. Indirectly, dirty phrases may be able to create the extra nudge a politician needs in a competitive campaign. Here’s the vulgarity effect, mapped:

“[T]he positive effect of cursing seems to apply to the whole electorate, as this effect did not vary as a function of participants’ gender, education, involvement in politics, and self-reported position on the left–right political spectrum,” the authors write.

But, as Cavazza advises, politicians shouldn’t go overboard just yet.

Probably there is a “saturation point”, that is an amount of vulgarity that backfires. We are currently carrying out another experiment in which we manipulate both the amount of swear words in the discourse (2 or 4 or 6 or none as control) and the repetition (one or more different discourses). In this way we will be able to see if the persuasive effect of swearing is linear (more swearing more appealing) or curvilinear (some swear words work but are too much detrimental?).