Unlike protected lands, marine protected areas can’t be staked with signposts — and, without clear boundaries, mariners can easily drift into areas where they don’t belong. But there might be a technological fix for that dilemma.

By Elizabeth Devitt

In 2001, the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary added the Tortugas Ecological Reserve, just west of the Dry Tortugas, where fishing and anchoring are prohibited. However, this area wasn’t marked on the nautical charts of a foreign-flagged merchant vessel that unwittingly destroyed pristine coral reefs when it weighed anchor there in 2002, says Mark Young of the U.S. Coast Guard. (Photo: Courtesy of U.S. National Park Service)

When a large swath of the Ross Sea in Antarctica earned marine protected area (MPA) status late last year, becoming the world’s largest MPA, it was hailed as an ocean conservation victory. Officially designating the territory as protected may only be the beginning of protecting it though.

Unlike protected lands, these waters can’t be staked with signposts — and, without clear boundaries, mariners can easily drift into areas where they don’t belong. Given that they’re often far from lines of sight, overseeing these ocean havens is also challenging.

To improve awareness and management of these special places, a team of technology experts, mapping specialists, and lawyers partnered with private enterprises and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to make it easier and more affordable for MPAs to live up to their names.

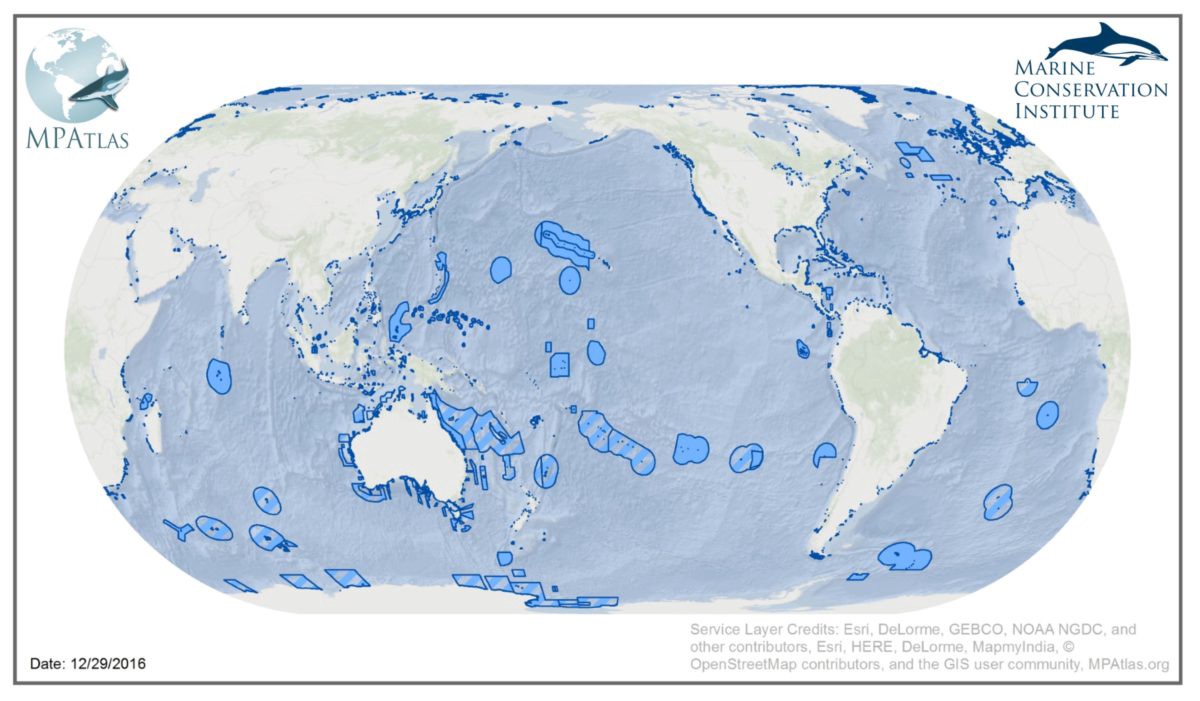

Worldwide, there are more than 13,500 MPAs, according to the Marine Conservation Institute, a non-profit organization based in Seattle. These MPAs are created for many reasons, from preserving historical shipwrecks and cultural sites to conserving biodiversity and marine species. While most of these protected areas are off limits to commercial fisheries, they are often open to recreational or subsistence fishing and public access.

There are more than 13,500 MPAs worldwide, yet that represents less than 3 percent of the word’s oceans, according to the Marine Conservation Institute. (Map: Courtesy of Marine Conservation Institute)

“In most cases, we want people to enjoy these amazing places,” says Lauren Wenzel, director of the NOAA’s National Marine Protected Areas Center based in Washington, D.C. “That’s how you build support for ocean protection.”

With restrictions that vary by location, it can be difficult for mariners to know what kinds of regulations apply in any given ocean space, or even to be aware that they have entered into a protected area.

Although navigation charts may provide details on some protected area boundaries, they are primarily intended for safety: to keep vessels away from reefs, rocks, and hidden shoals. Even if MPAs and their restrictions could be added to these maps, there wouldn’t be enough room for it all.

“Just one spot in the sea could be overseen by a number of different agencies, for varying purposes, each with their own corresponding regulations,” says Mimi D’lorio, data manager for the NOAA’s MPA Center. “This can make it hard to communicate these regulations to the public in a clear and consistent way.”

Hidden Assets

With the goal of bringing all the MPAs into one data set — and making it accessible from a boat — experts in software design, coastal law, and geography formed a team. Led by Virgil Zetterlind, manager of the California-based non-profit Protected Seas, the group first concentrated on mapping the United States’ coastal areas.

“It wasn’t like we could go looking in one comprehensive source,” says Zetterlind of the almost two-year task. Most of Protected Seas’ information was gleaned with guidance from the NOAA and other agencies. About one-third of the time, the team discovered MPAs had been described in regulations by latitude and longitude — but never digitally mapped.

Once the team translated the key restrictions and allowances into plain language, they created layered maps so boaters could pinpoint their location with regard to MPAs. These maps have been integrated into electronic charting software offered by Navionics, an international chart provider based in Italy. Now, for example, a boat captain with an iPad can turn on the MPA layer and tap the map to see whether their vessel is in a restricted area. For more detailed information about allowed activities, links to official sources are sited within the maps. Boaters without electronic charts can freely view the MPA maps from a mobile-friendly public website, and the charts will eventually be available for smartphones and tablets.

Every possible restriction isn’t listed on these maps. As D’lorio points out, MPAs may be managed for many things, including oil and gas extraction, shipping traffic, wind farms, cultural sites, historic shipwrecks, ecosystems, biodiversity, or human recreation. The Protected Seas database focuses on the extraction of fish and other living resources, “the stuff you can eat,” she notes.

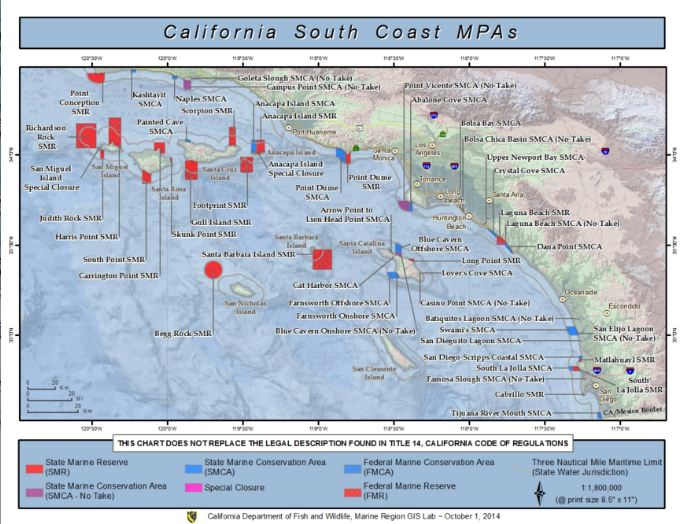

The mapping challenge: This is just the Southern California coast. The U.S. Coastline stretches 93,572 miles and more than 1,700 MPAs have been created in U.S. waters — including areas in the Great Lakes — by a mix of federal, state, and local legislation, voter initiatives, and regulations, each established for its own specific purpose, according to NOAA. (Map: California Department of Fish & Wildlife)

Now that the U.S. version has launched, Zetterlind’s team is working on international sites. Their long-term goal is to format all the data for the next generation of electronic charts to fit the standards for uniformity set by the International Hydrographic Organization, a nautical safety and marine protection group based in Monaco.

“Using technology to help show those MPA boundaries would be a big step forward to raising public awareness,” says Mark Young, senior officer of conservation enforcement for The Pew Charitable Trusts in Washington, D.C.

While he wasn’t involved in this project, Young has had ample experience with the complexities of navigating MPAs during his previous 23-year post with the U.S. Coast Guard. In his current role, Young campaigns to end illegal fishing, an activity aided by the remoteness of the high seas. When MPAs can’t be easily monitored, enforcement is ineffective and MPAs become “paper parks which don’t do anybody any good,” he says.

Sea-curity

To improve surveillance in out-of-sight locales, Zetterlind also developed software for basic radar systems available from most boating supply stores. For less than $100,000, MPA managers can create a 24/7 marine monitor (M2) system — which covers the cost of buying the radar, building a land tower or base on a trailer, and ensuring a power supply and Wi-Fi link. The custom software converts the radar data into user-friendly information that makes it easy to track boats and add timestamps and geo-locations. The data is portable; it can be relayed, downloaded, or transferred on USB drives.

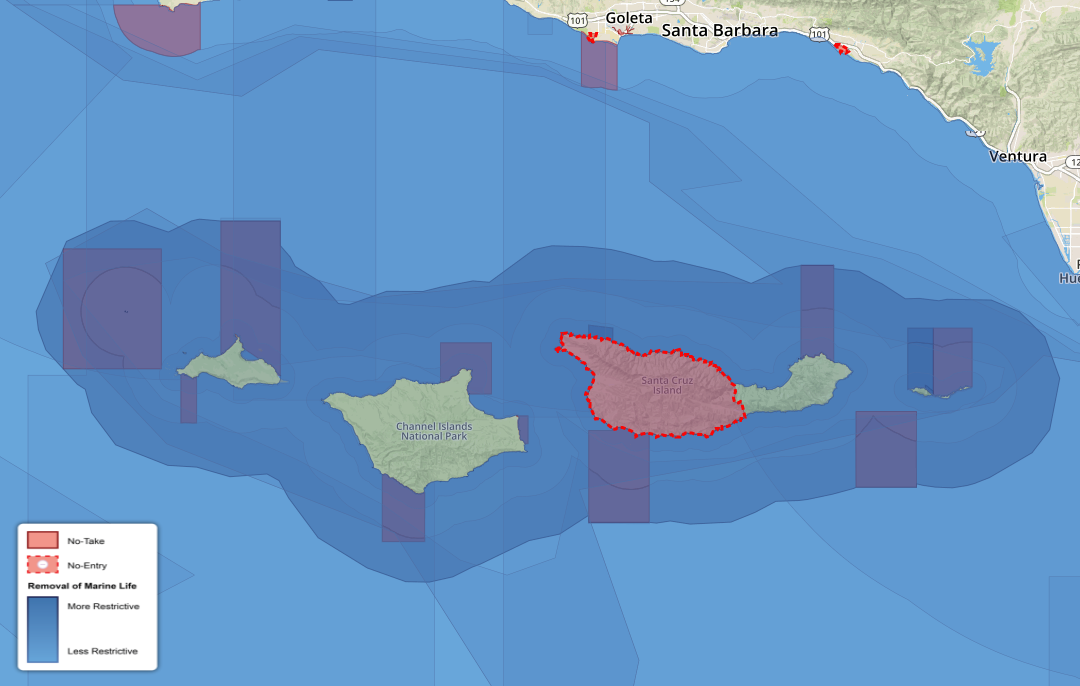

A layered map of the maze of protected areas off the Santa Barbara coast in Southern California. (Map: Courtesy of Protected Seas)

“For most established protected areas, there isn’t much hard data about prior or existing usage,” Zetterlind says. “Without understanding how an area is used, it’s harder to say how human and capital resources should be applied. Do areas need two patrol ships a day or 10? Which way should they go?”

With an M2 system, even basic information, such as counting boats, can provide useful long-term patterns. That information is important for economics, enforcement, and figuring out whether management goals are being met. It can also help funding organizations see independently verified results. Although the systems are still in the proofing stages, Zetterlind is confident that, once they can demonstrate the usefulness of the collected data, MPA managers will quickly come on board.

“We’re trying to obtain that ever-elusive balance of human use and protection and we can’t be everywhere all the time, so that’s where technology comes in,” says Sean Hastings, technical advisor for a new M2 installation off the Southern California coast and the NOAA’s resource protection coordinator for the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary in California.

With the enthusiasm of someone who once patrolled the protected territory by seaplane for four hours every two weeks, Hastings quickly ticks off the advantages of M2: it’s safer because he’s not flying; it’s economical and can run on solar power; and the vessel-tracking analytics give 100 percent coverage every day to reveal hourly, daily, and seasonal patterns of use. Like all radar, he notes the system’s range is determined by atmospheric conditions and potential obstructions.

As a rough comparison, Hastings estimates the cost of two flyovers a month with personnel would be about $10,000, adding up to $120,000 a year for less than 100 hours of monitoring, while the radar set-up offers around-the-clock coverage for the price of about $100,000, plus maintenance.

“This technology doesn’t replace enforcement or monitoring, it enhances it,” Hastings says. He hopes to have the system fully operational in the next few months. “I’m just managing a relatively small piece of the California coast. Imagine what’ll happen when all the other ocean managers and park managers realize the potential of this technology.”

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.