(Photo: Joey Foley/Getty Images for Payless ShoeSource)

Last week, the discount shoe retailer Payless ShoeSource filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and announced it will close 400 brick-and-mortar stores throughout the United States and Puerto Rico. The announcement comes on the heels of a seemingly unending parade of bad news from traditional retailers in recent months. So far this year, Macy’s, J.C. Penney, and BCBG, among others, have all announced significant store closures.

Analysts who study the retail sector are pretty much unanimous in their assessment of what’s ailing traditional retailers: There are just too many big-box stores and hulking suburban malls in the U.S., especially given the growing dominance of online retailers like Amazon. Here’s what Richard Hayne, the CEO of Urban Outfitters, told analysts on a conference call last month:

Retail square feet per capita in the United States is more than six times that of Europe or Japan. And this doesn’t count digital commerce. Our industry, not unlike the housing industry, saw too much square footage capacity added in the 1990s and early 2000s. Thousands of new doors opened and rents soared. This created a bubble, and, like housing, that bubble has now burst. We are seeing the results: doors shuttering and rents retreating. This trend will continue for the foreseeable future and may even accelerate.

Not surprisingly, these store closures have been accompanied by another kind of economic pain: layoffs. Challenger, Gray & Christmas, a job placement firm, calculates that traditional retailers have announced over 200,000 layoffs over the last four years — and 38,000 already in 2017. In fact, according to the March jobs report, which was released last Friday, the number of retail jobs in the U.S. declined by 30,000 last month (after a similar decline in February).

And while Amazon announced earlier this year that it would hire 100,000 new employees in 2017 and the first half of 2018, is the growth in e-commerce enough to make up for the destruction of traditional retail jobs?

Some argue it’s not. “The number of jobs we are losing in retail outpaces the number being created in the sectors that are taking their place,” Andrew Challenger, the vice president of a job placement firm, told the New York Times back in January.

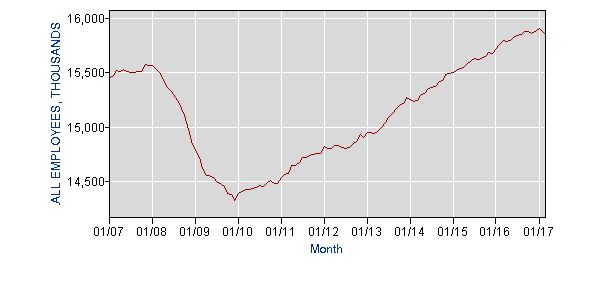

But the data tells a more nuanced story. Employment in the entire retail industry (including both traditional and online retailers) is now well above pre-Recession levels. The chart below, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows employment (in thousands) in the retail sector:

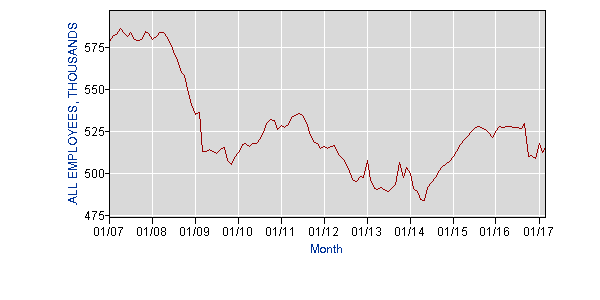

That aggregate measure, however, obscures the radically different experiences of specific retail industries. Here, for example, is what happened to employment at electronic and appliance stores (one of the hardest-hit retail categories):

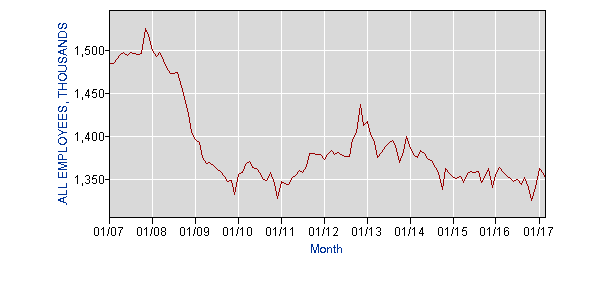

And here’s employment at “clothing and clothing accessories” stores, another retail category that’s been struggling of late:

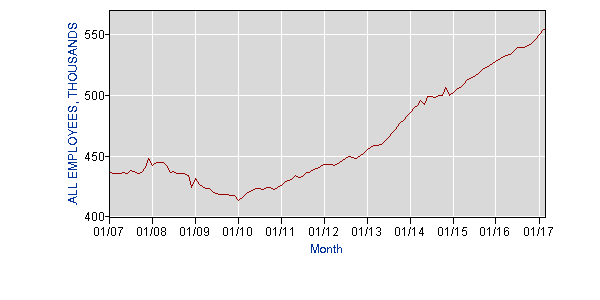

By contrast, here’s what happened to employment at “non-store” (i.e. online) retailers:

A paper published last month by the Progressive Policy Institute, a center-left think tank, attempts to definitively answer the question of whether e-commerce has destroyed more jobs than it has created.

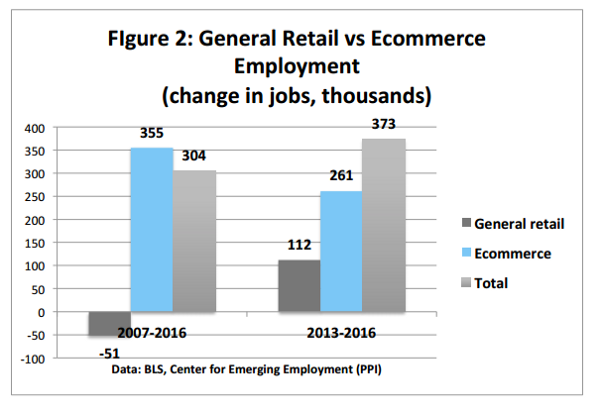

The paper’s author, economist Michael Mandel, compares job losses in the general retail sector with job gains in the online shopping and “general warehousing” industries. As the chart below shows, he found that “the e-commerce sector added 355,000 jobs from 2007 to 2016 — more than enough to compensate for the 51,000 jobs lost in the general retail sector.”

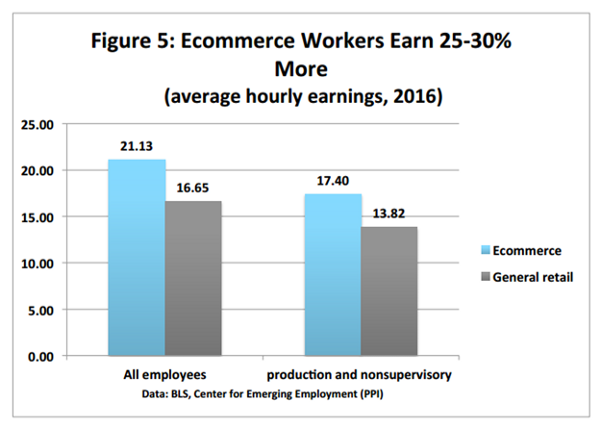

What’s more, as the chart below (also from Mandel’s paper) illustrates, jobs in e-commerce tend to pay better than traditional retail jobs, even among non-supervisory employees. Even Amazon’s now infamous fulfillment centers pay 30 percent more than traditional retail jobs (according to the company).

This seems to be true even when comparing workers across similar professions. E-commerce workers in the “office and administrative support” category, for example, earn 28 percent more than traditional retail workers in the same category.

There’s little doubt that e-commerce companies have dramatically changed the retail industry, and delivered enormous gains in efficiency and productivity. Yes, there would be more traditional retail jobs in this country if Amazon didn’t exist. Companies like Amazon are able to produce the same amount of economic activity as traditional retailers, with many fewer man hours of work. But, in general, those kinds of productivity increases are considered a good thing; it’s virtually impossible for the economy to grow in a meaningful way without such leaps in productivity. And while there might be more traditional retail jobs in an Amazon-less world, there would likely be fewer better-paying software developer jobs.

But there is one enormous caveat to this rosy view of e-commerce: the workers being laid off by Macy’s and J.C. Penney stores in economically distressed exurbs aren’t necessarily the same workers getting jobs at Amazon. That doesn’t mean we should cling to traditional retail jobs—which are frequently characterized by low wages, high turnover, on-demand scheduling, and skimpy benefits — any more than we should have clung to buggies or horse-drawn plows in the 1900s. But it does mean we should do more to both prepare future generations for a different kind of economy, and to help the retail workers who have already been or likely will be displaced by the relentless march of technology.