In 1991, as Aaron Wolf was finishing his doctoral dissertation, the Madrid Middle East peace process was just getting under way. The two sides decided to tackle five sets of regional issues, including the equitable division of water resources. As a budding expert on the subject — his research focused on the Jordan River and its dual role as “a flashpoint and a vehicle for dialogue” — Wolf agreed to advise the U.S. team designing the talks.

Fifteen years later, one remnant of that failed attempt at Palestinian-Israeli peacemaking remains: the water negotiations. “They still go on,” Wolf says. “The two sides have cooperative projects. In the second intifada, when they realized how much violence there was going to be, they took out a joint advertisement asking both sides to try to protect the water infrastructure.”

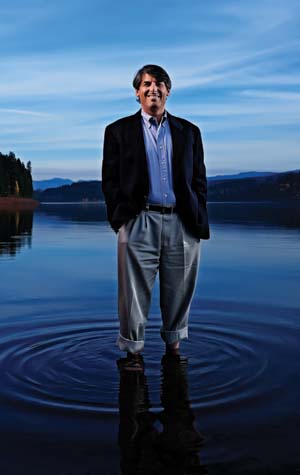

The lessons of that enduring success have stayed with Wolf as he has pursued his remarkable dual career, as an Oregon State University scholar studying water-resource issues and a hands-on mediator of water disputes around the world. Water, he has come to understand, is so central to the human experience that it can help even bitter enemies find common purpose.

“That’s what’s so heartening about this,” the gentle geoscientist says. “Water can be used as a means for people of different ideological backgrounds to talk about a shared vision of the future.”

Wolf’s calling takes him all over the world, wherever bodies of water — usually rivers — are shared by two or more countries. A dam built upstream, on one side of the border, will affect the flow of water downstream on the other side; whose needs are more important? Is generating electricity the priority? What about pollution?

“Everywhere you find real tension,” he says, “you’ll also find shared rivers.”

“Aaron has shifted the way the whole world thinks about water,” says Anthony Turton, an expert on water management at South Africa’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. “His database at OSU is highly cited and is regarded as being the most authoritative. That database shows that violent conflict over water is rare but peaceful interactions are many.

“We are finding that water, rather than being the driver of conflict, is the one resource that unites people. It is simply too important to fight over.”

Like a stream meandering from the mountains to the marshlands, Wolf’s work courses through a wide variety of disciplines. Facilitating water-resource disputes requires a strong working knowledge of geography, geology, ecology, politics, diplomacy and — at least the way Wolf handles the disputes — spirituality.

A professor at OSU’s Department of Geosciences, Wolf founded and directs a postgraduate program in which budding economists, engineers and ecologists add water-conflict resolution to their skill sets. He developed and coordinates the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, a massive compilation of more than 400 water-related treaties accompanied by maps, negotiating notes, background materials and related news stories.

In addition, he co-founded and directs the Universities Partnership for Transboundary Waters, a consortium of like-minded colleagues at 10 educational institutions located around the world. Its goal is to develop a new generation of water-conflict experts based on every continent who can provide one another with “a community of support as they work in these difficult settings.”

“Aaron’s work addresses what is probably going to be the biggest recurring policy issue for the next 50 years,” says Sherman Bloomer, dean of the OSU College of Science. “It’s one of the very best things that has happened at Oregon State at the time I’ve been here.”

Wolf grew up in a desert. Two deserts, actually. Born in pre-revolutionary Iran, where his father taught English literature, he spent part of his childhood in California and part in Israel, where his family relocated to honor what he calls their “Zionist ideals.”

Moving from the Middle East halfway across the world and back again must have been jarring, but what ultimately impressed Wolf were the commonalities of his two homelands. Both California and Israel were, and are, arid places. Water — where to get it, how to conserve it and who is challenging one another for it — was an urgent topic of discussion in both societies.

As he absorbed a love of learning and sense of spiritual mission from his family, Wolf developed an awareness of water as a life-giving commodity. His interest in natural resources and how they are used was refined at San Francisco State University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in geography.

Wolf was drafted into the Israeli army (he holds both American and Israeli citizenship), serving in Lebanon and on the front lines of the first Palestinian uprising. “That’s when I got really interested in conflict resolution,” he says. “When you’re in uniform, you realize there’s got to be a better way.” After completing his military obligation, he moved back to the U.S., earning a master’s degree in water resource management and a doctorate in land resources from the University of Wisconsin.

After finishing his work with the State Department for the Madrid peace conference, Wolf began his academic career at the University of Alabama. “They get 60 or 70 inches of rain a year,” he notes, “but there is still tension between Alabama, Florida and Georgia (over water). I did a lot of thinking conceptually about what happens within a watershed. What are the dynamics?”

His attempts to apply scientific knowledge to political and diplomatic disputes were noticed by officials at Oregon State, who hired him to join the faculty in 1998. “Doing effective science requires finding partners in places other than your own discipline, if you want that science to have any effect,” OSU science dean Bloomer says. “You’ve got to have people who understand how to take science and introduce it into the policy arena. That is particularly true of water. A great deal of the point of doing the science is to provide input that will lead to sound policy decisions.”

As Wolf tells it, his transition from academic observer to participant in negotiations occurred gradually: “You’d have a conference that would turn into a workshop that would turn into a facilitation.” The first dispute he formally mediated involved the Salween River, a body of water shared by China, Burma and Thailand.

“All three countries have development plans, and no two sets of plans are compatible,” he explains. “There is lots of political tension. China has huge plans for dams all through the southern part of the country, which are the headwaters of a lot of Asia’s rivers. There won’t be enough water for everybody’s needs, that’s for sure.”

He has also facilitated talks between the former Soviet nations of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia — no small feat, given that the latter two nations are mortal enemies. “I and some other folks were able to craft a way where Azerbaijan and Georgia talked to each other and Armenia and Georgia talked to each other,” he says. “They were able to develop a process where they coordinated when they couldn’t collaborate.”

Wolf was searching for better catalysts for compromise when, in 2002, he realized what he was missing.

“I was having a conversation with someone at the World Bank who is involved in water conflicts and also has a deep spiritual life,” he says. “We were talking about a set of images I use in negotiations. I have a visual of the watershed with the political boundaries on it and one with the political boundaries taken off. (When you remove the boundaries) suddenly everything looks very different. He told me, ‘That looks like an analog for spiritual transformation.’

“For me, that was an ‘aha’ moment. People in an academic or scientific context often have a reluctance to think about something as ephemeral as spirituality. We in (the Western world) separated out rationality from spirituality during the Enlightenment. In a lot of the world where I work, there is no distinction between the two. They’re one integrated whole.”

Suddenly, Wolf realized the standard Western model of conflict resolution he was using was inadequate, if not irrelevant.

“Whenever there are attempts to resolve real conflict, where there is deep pain or anger, there are transformative moments —profound shifts in thinking,” Wolf says. “You know it when it happens, and it isn’t about rationality at all. It’s about sudden transformation. I would see this over and over again, where everybody was suddenly thinking profoundly differently. I started asking, ‘How can you focus in on that moment of transformation?’

“Well, who thinks about transformation in a systematic way? The spiritual community does. There are people who have spent a lot of time thinking about conflict and anger and how to transform them into more peaceful ways of thinking. We’ve never tapped into that knowledge in the conflict-resolution world.”

Excited by the revelation, Wolf arranged a 2004 meeting in Vatican City between spiritual leaders and water-conflict negotiators. It was not, in his mind, a success; the disconnect between the participants was all too evident. “From that meeting, I started to understand there was room for dialogue, but it would take a lot more time,” he says. “Fortunately, being an academic, I had a sabbatical immediately afterwards, so I got to spend the following year studying spiritual transformation in the Middle East and Southeast Asia and specifically think about how it might apply to conflict management.

“I was in Israel; I spent time traveling to Jordan and Egypt. I studied the Jewish Kabbalah and a bit on Sufism and Christian (mystical) traditions. I then spent a summer in Thailand learning from a Buddhist monk who conducts negotiations over timber issues. That’s where it really came together for me. I had a chance to look deeply at these models and think about how you can do conflict resolution better with these understandings.”

Among the tools Wolf has incorporated in his conflict-management training kit is an understanding of the hierarchy of human needs, as articulated by psychologist Abraham Maslow. “The idea is there are four categories of needs — physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual — and they are best achieved in some kind of sequence,” Wolf says. “Maslow popularized this concept in the West, but it can be found in all spiritual traditions. My training workshops in conflict resolution are now structured to go through those different levels.”

The importance of doing so is illustrated in the ongoing Middle Eastern talks, which Wolf still helps facilitate from time to time. “When Israelis and Palestinians are talking to each other about water resources, Palestinians are talking about the need for water on a physical level,” he notes. “In the Gaza Strip, people literally don’t have enough water for their basic human needs. Water is also an emotional issue for them; it’s a representation of the Israeli occupation. It’s controlled by somebody else.

“In Israel, nobody is dying of thirst. What’s more, they’re largely in control of their own aquatic destiny. With their physical and emotional needs met, they think of water in intellectual terms. How much do we use in agriculture as opposed to for residential use? How much do we desalinate, and at what price?”

This Israeli attitude, Wolf says, leads to “a profound disconnect” with the Palestinians. “If you literally don’t have enough to meet your basic human needs,” he says, “you can’t remove yourself enough to think about whether drip irrigation is the most economically efficient use of water.

“So (I have tried to emphasize the fact) that everybody’s basic human needs must be taken care of, and whatever emotional scars they have about the past need to be addressed. Then you can move it onto an intellectual level.”

Wolf has gotten into the habit of starting negotiations by asking everyone involved to tell stories that describe their relationship to the source of water in question — what it means to them. “At the end of the introductions, instead of having established a hierarchy, the people notice their commonalities with the others in the room,” he says.

Also, he says, he emphasizes the need for adversaries to genuinely listen to one another. “The profound spiritual practice of deep listening is in every spiritual tradition, but we in the West do it so badly!” he says. “I was told this joke: ‘In America, what’s the opposite of speaking?

“‘Waiting to speak!'”

Wolf can’t talk in specifics about the negotiations he has overseen in recent years; most are ongoing, and coming to terms on a water treaty can take 10 or even 20 years. In 2009, he expects to be returning to the Middle East and Southeast Asia, “where I’ve been working a lot lately. There’s a lot of demand on resources in that area. You want to encourage development for poverty alleviation, but you don’t want to make the same mistakes we’ve made with some of our big dams.”

With the world’s population growing and rainfall patterns shifting due to climate change, Wolf’s general glass-half-full attitude will surely be tested in coming decades. Even today, he says, “Two-and-one-half (million) to 5 million people die every year because of a lack of access to safe, clean water. That’s on the same level of magnitude as AIDS or malaria. It’s a huge catastrophe now, and climate change will beget more variability in the hydrologic cycle, including longer droughts and bigger floods.”

On the other hand, Wolf notes that “all spiritual traditions — not just (those) in the religions that come out of the desert — seem to tap into water as healing, soothing and cleansing.” This shared sense of sacredness gives him hope for the future, as does the resilience of many water agreements. “India and Pakistan have a water treaty that has survived since 1960 — through two wars,” he says. “In the middle of one of the wars, India made payments to Pakistan as part of their treaty obligations.”

“I think water hits us at a profoundly different level than other resources,” he adds. “People are willing to do horrible things to each other. What they seem not willing to do is turn off each other’s water.”