The health care debate in Congress for months focused on the “gang of six,” a group of three Democrats and three Republicans in the Senate Finance Committee who spent endless hours barricaded on the Hill trying to divine a compromise that members of both parties could support.

Today, the Finance Committee finally voted on the bill that work ultimately produced. And just one Republican said “yea.” It seemed a strange conclusion to what was supposed to be the most sincere and serious-minded bipartisan effort in town.

Barack Obama might deride this as “politics as usual,” a bitter party-line vote as an act of political symbolism and not an effort at meaningful policy-making. But in fact, the moment — and the entire health care debate — represents the culmination of a decades-long trend in the capitol: There is no longer a center in the Senate.

Or, as William Galston at the Brookings Institution put it, the most conservative Democrat in the Senate is still well to the left of the most liberal Republican.

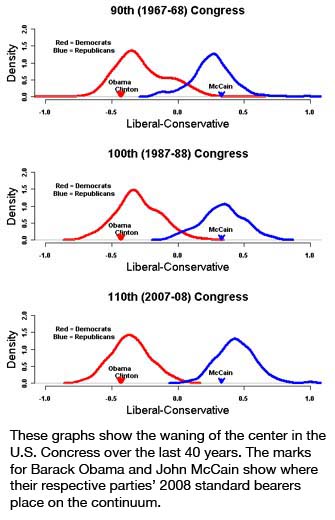

Keith Poole, a professor at the University of California at San Diego, and several other political scientists have illustrated exactly what this fact looks like. The group developed a system (best explained here by mathematician Jordan Ellenberg) that plots individual politicians, and entire classes of Congress, on a numeric scale from liberal to conservative based on their roll-call votes. The tool allows for the direct comparison of politicians over time.

These three histograms show the steady polarization of Congress since the 1970s: In the most recent data, there is virtually no overlap between the parties (movement that mirrors the more widely researched polarization of the American public). As Poole dryly sums up: “Modern American politics is completely dysfunctional. There are no moderates left in either political party.”

He attributes the trend to the rightward movement of the Republican Party after the civil rights movement and the realignment of Southern Democrats. Individual politicians didn’t become more conservative; rather, moderates were slowly replaced, just as Southern Democrats were largely replaced by Republicans.

The shift follows wide ideological overlap between the two parties from roughly World War I through the early 1960s. (Poole has analyzed congresses dating back to the end of Reconstruction here).

The full data suggests that this is not just a polarized moment in politics, but the most polarized the legislature has been in more than a century. That makes Obama the first president to try to push a sweeping entitlement reform through a legislature with no center.

The problem is compounded by what Poole calls the one-dimensional nature of Congress today, where the differences between politicians boil down to the question of government’s role in the economy. Representatives were split in the past along regional lines as well due to racial issues, but with the outlawing of segregation, most of those issues today have been recast as economic questions of redistribution.

As for where we go next: “Something’s got to break,” Poole said. “This can’t continue forever.

“I think what you’re seeing now is the crack-up, and the crack-up is that Congress will not be able to control entitlement spending. Democrats can pass things because they’ve got these big majorities, but they won’t stick.”

Poole’s parting thought: Even if Democrats return to their mid-20th century extended majority in Congress, the U.S. could never become the type of social democracy modeled in Europe. Europe can afford to devote a larger share of GDP to social programs; it has outsourced much of its defense (and defense of assets like global shipping lanes) to America. That means the U.S. may not be able to afford health care for its own because it pays for security for the world.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.