In 2015, Nobel economics laureate Angus Deaton and renowned economics professor Anne Case published a disturbing diagnosis for American society: White people are dying.

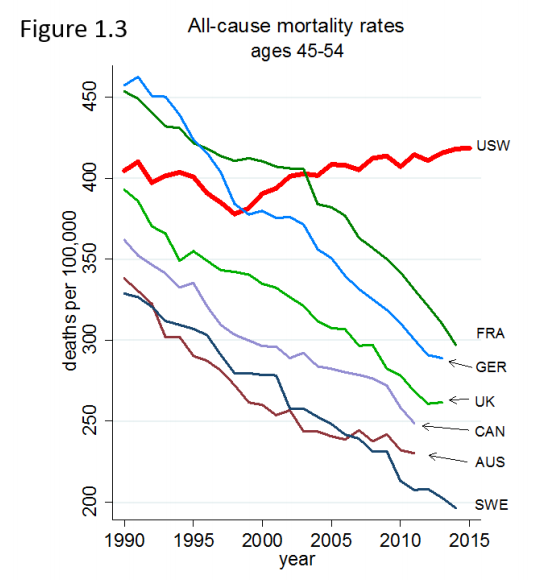

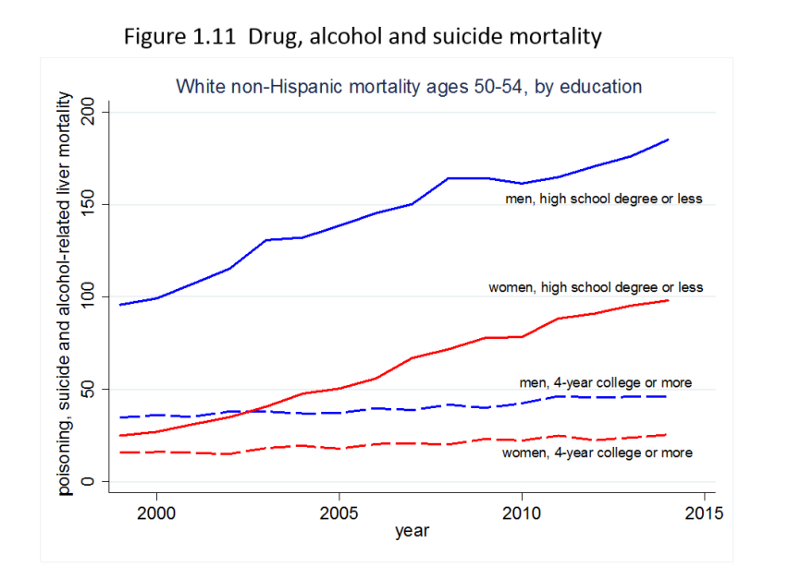

To be more exact, Case and Deaton found that middle-aged, non-Hispanic Americans without a college degree experience a significantly higher mortality rate than those in advanced countries like the United Kingdom or Germany. While everyone else in the United States is getting healthier and living longer, it’s that segment of whites who accounted for “half a million deaths” between 1999 and 2013.

To scientists, the sudden die-off in middle-of-the-road white Americans constitutes a phenomenon “unprecedented in the annals of public health among developed nations” with the exception of the post-U.S.S.R. deaths of Russian males and, in some ways, the first shock waves of the AIDs crisis in the early 1980s.

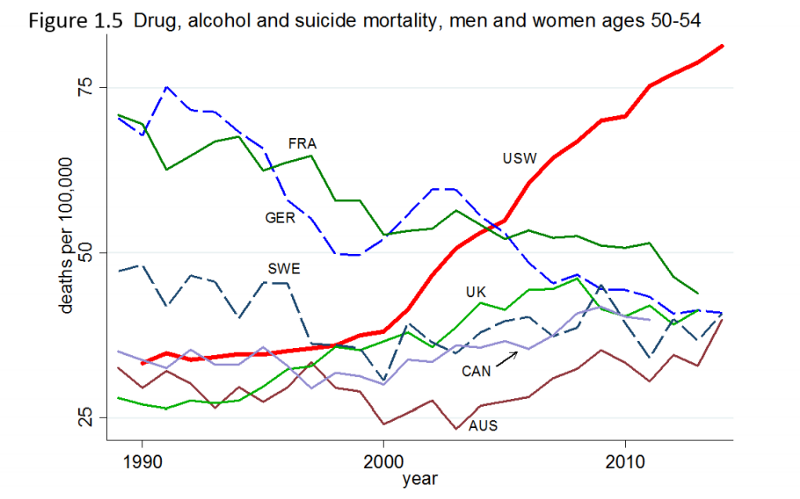

A similar analysis of American morbidity conducted in 2016 by the National Center for Health Statistics found that more Americans were killing themselves than at any other time in the last three decades — and that the sudden uptick in suicides was concentrated on the same middle-aged, economically stagnant white Americans who showed a turn toward death in Case and Deaton’s 2015 analysis.

The evidence seemed clear: 19th-century sociologist Emile Durkheim’s pioneering research connecting suicide rates to social alienation and disenfranchisement is alive and well in those Americans left behind by the demographic and technological transformation of the U.S. “The role of suicide, drugs, and alcohol in the white midlife mortality reversal,” Paul Starr observed in TheAmerican Prospect, “is a signal of heightened desperation among a population in measurable decline.”

A new analysis by Deaton and Case, published by the Brookings Institution, offers a 21st-century interpretation of Durkheim’s classic theory of anomie: “[c]umulative disadvantage,” an increasingly diminished chance at success in every arena from work to marriage “triggered by progressively worsening labor market opportunities at the time of entry for whites with low levels of education.” The result of cumulative disadvantage is, in their own words, a “Durkheim-like recipe for suicide”:

This process, which began for those leaving high school and entering the labor force after the early 1970s — the peak of working class wages, and the beginning of the end of the “blue collar aristocracy” — worsened over time, and caused, or at least was accompanied by, other changes in society that made life more difficult for less-educated people, not only in their employment opportunities, but in their marriages, and in the lives of and prospects for their children. Traditional structures of social and economic support slowly weakened; no longer was it possible for a man to follow his father and grandfather into a manufacturing job, or to join the union. Marriage was no longer the only way to form intimate partnerships, or to rear children. People moved away from the security of legacy religions or the churches of their parents and grandparents, towards churches that emphasized seeking an identity, or replaced membership with the search for connections. …

These changes left people with less structure when they came to choose their careers, their religion, and the nature of their family lives. When such choices succeed, they are liberating; when they fail, the individual can only hold him or herself responsible.

This phenomenon, in Deaton and Case’s account, presents itself not merely through suicide but also through “death of despair,” mortality rates tied to drug and alcohol abuse, suicide, and other self-inflicted wounds.

This experience isn’t exclusive to areas we might assume have high concentrations of middle-aged, poorly educated whites directly affected by the collapse of American manufacturing. The epidemic has spread nationwide since 1990, according to Deaton and Case’s research.

This isn’t just because of the regional evaporation of manufacturing jobs. Despair, for those whites left behind by the progress of the nation, knows no zip code or industry, only the resources available for people to make their own way — resources increasingly unavailable to Americans without a college diploma.

Unfortunately, this newfound experience of cumulative disadvantage for middle-aged whites, once the epitome of American social power, looks immune to policies that emphasize bolstering the economic resources of the socioeconomically disadvantaged.

“Policies, even ones that successfully improve earnings and jobs, or redistribute income, will take many years to reverse the mortality and morbidity increase, and that those in midlife now are likely to do much worse in old age than those currently older than 65,” Deaton and Case write. “This is in contrast to an account in which resources affect health contemporaneously, so that those in midlife now can expect to do better in old age as they receive Social Security and Medicare.”

In some policy spheres, there’s was a belief that Donald Trump’s election would prove a catharsis for middle-aged white Americans, replacing the despair seen by Case and Deaton with a sense of hope similar to that experienced by portions of the American electorate after the election of Barack Obama in 2008. But Deaton and Case’s research offers a clear counter to that notion: Populism can treat the symptoms of what ails white America, but it can’t fix the root cause.