A weekly newsletter for Pacific Standard Premium members.

Early Access to Online Features

Available Now for Premium Members: Staff writer Kate Wheeling travels to Peru to meet Australian plant ecologist Brenton Ladd in “The Great, Chaotic Biochar Experiment.” Ladd wants to re-engineer the notoriously nutrient-poor soils in the Amazon and, in the process, save the world’s trees. But first, he has to convince farmers that he’s not just another crazy gringo with a bad idea.

And: Morgan Baskin crosses snowy terrain to find a river moving through the beautiful mountains of Yellowstone National Park in her story “The Poison in Our Water“—a river that is probably full of plastic contaminants. Baskin spoke with the scientists who are sorting out the best way to capture and measure the harmful microfibers that exist in most of our fresh water.

Plus: Sarah Fuss Kessler visits Golden Valley High School in central California for her story “How Women’s Studies Is Helping Rural Teens Fix Their Social Culture“—a school in the agricultural town of Merced, where Annie Delgado is using pioneering courses to fill in the gaps left by more traditional curricula; in “Welcome to Asbestos,” Chrystal Chen profiles Pierrette Théroux, the founder of the Asbestos Historical Society; and Jeremy Lybarger visits the makeshift studio of an Afghan variety show that can help us understand cultural diasporas.

Visit psmag.com/premium for early access to all the stories from our May issue.

(Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

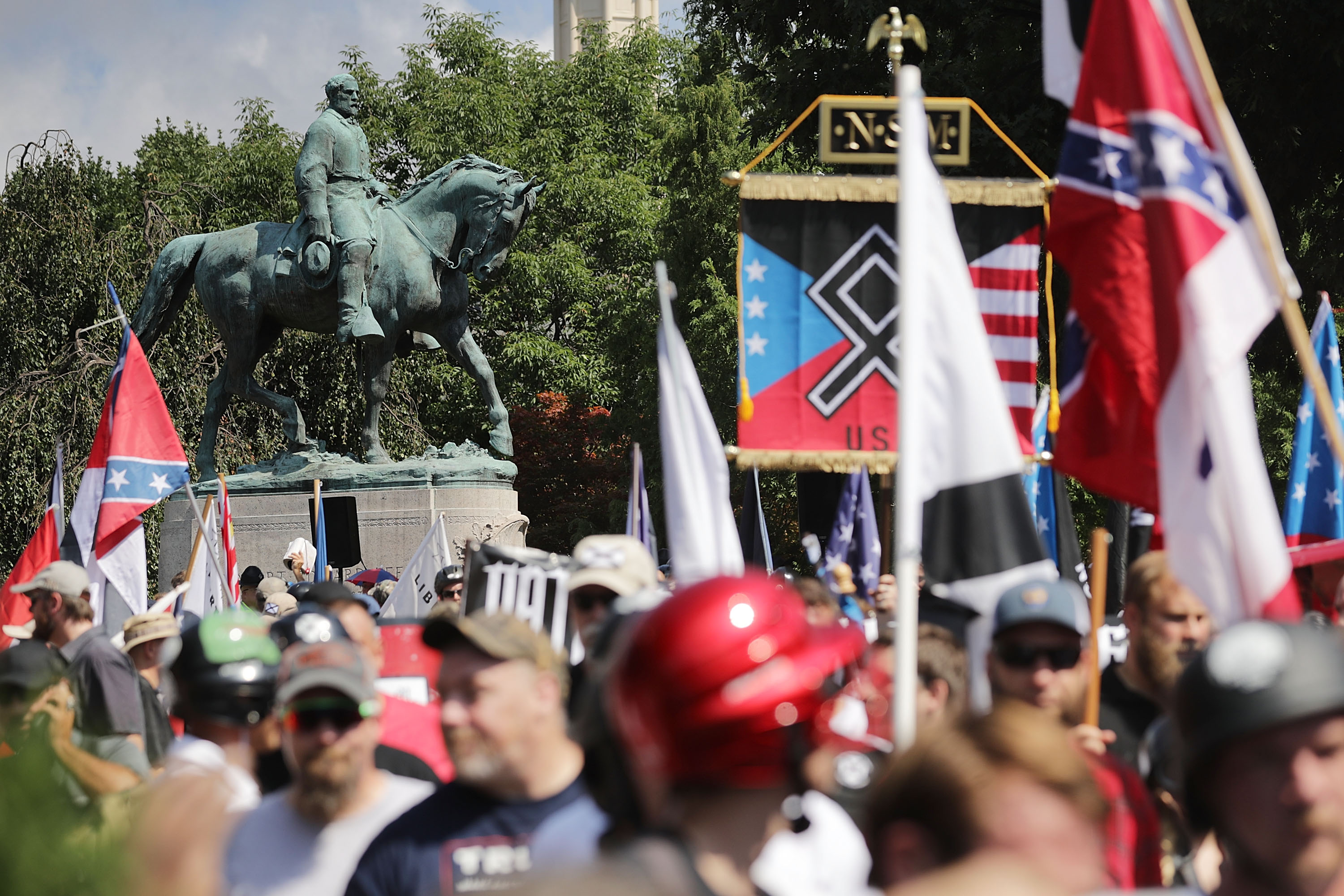

Don’t Miss: Polarizing Political Divides

News and analysis from Pacific Standard on the biggest stories of the week.

The polarized nature of political discussion and the rise of nationalist rhetoric have been a point of concern both in America and abroad for quite a while. A rise in violence attributed to members of right-wing groups has brought the issue to the forefront again. This time, a Canadian citizen, Alek Minassian, drove a van into a crowd of pedestrians, killing 10, in the name of a 4chan movement that promotes misogynistic and racist ideology. Taking a step back, it’s worthwhile to look at our coverage of both the alt-right and the polarization of more conventional political dialogue to trace the growing roots of extremism that are festering in society and rejecting an inclusive democracy.

- Is the Christian right actually driving people away from religion? New research shows that when evangelical organizations raise their profile by sponsoring a high-profile political campaign, a backlash ensues.

- Contributing writer David M. Perry has written about the issue of white, male radicalization for PS on numerous occasions. His most recent piece, “How to Fight Alt-Right Terrorism,” calls for systemic change in dealing with this issue; in the past, he has investigated the places where these men are being radicalized. The roots of these movements can also be found on college campuses, where conservative groups have made inroads in taking control of student governments and silencing their critics.

- One of the places where radicalization increasingly occurs is on a Web forum called 4chan. Dale Beran sheds light on this obscure corner of the Internet in his piece “Who Are the ‘Incels’ of 4chan, and Why Are They So Angry?“

- In the midst of growing consternation about the future of the country, Bridey Heing reviews three new books that offer bracing lessons from European and Latin American history to help explain rising authoritarianism in the United States and beyond.

- Malcolm Harris argues that columnist David Brooks of the New York Times should stop using tribalism to bolster a specific myth about American exceptionalism.

- When it comes to how we formulate our ideologies, new research shows that it’s often not about the actual issues, and that voting patterns can be influenced by what people think members of their party should look like.

- What do you do if you find out your brother is the face of one the alt-right movement? Gabriel Thompson wrote about Josh Damigo, whose brother Nathan rose to infamy as a prominent white nationalist.

(Photo: Stephen Brashear/Getty Images)

Behind the Scenes: What It’s Like to Report on Your Parents’ Former Union

Staff writer Francie Diep wrote a piece for our State of the Unions Week that took a look at the different conditions faced by Boeing workers at its unionized plant in Everett, Washington, and the non-unionized plant in South Carolina. You can read that story here. Diep’s parents were both members of the union at the Boeing facility in Washington, and this is her story of covering an issue that hit close to home. Read the rest of our State of the Unions coverage here.

I grew up surrounded by Boeing-branded stuff: not just model airplanes, but also countless Boeing pens, Boeing notepads, Boeing first-aid kits, a blue canvas Boeing hammock, and a waffle-maker with a huge Boeing logo printed on its lid. My mom was an electrical engineer at the airplane manufacturer, and my dad, a machinist. Both are retired now. The goodies were all rewards they’d earned as Boeing employees, and union members.

Being a Boeing family in the Seattle-area during the 1990s and 2000s also meant I grew up with frequent strikes, including some of the biggest in company history. My parents seldom talked about either work or politics, so they wouldn’t say much about it. They would just be home for long stretches.

My parents immigrated to the United States in their late 20s, as Vietnam War refugees. They had no savings and no proof of the college degrees they had earned there. My dad took on assembly-line jobs to put my mom through school again, so that at least one of them would have a bachelor’s. Yet, despite these tough beginnings, by the time I was in junior high, we lived no differently from the middle-class friends I’d made in my small hometown. That reality would have been harder to achieve if my dad earned 38 percent less, as the non-unionized South Carolina Boeing machinists do, compared to those employed in Washington.

When it came time for me to pick a story to report for Pacific Standard‘s State of Unions Week, I was naturally interested in how Boeing’s unions, some of the strongest remaining in America’s private sector, were doing. It had been about a year since Boeing’s South Carolina plants voted not to unionize, in a decision that had been declared a sign of how organized labor would fare in the Trump era.

I was surprised by the prevalence and vehemence of anti-union rhetoric in the public discourse, but it turns out I shouldn’t have been. In a detailed survey of more than 3,000 union members at Boeing’s Everett plant, conducted in 2013, sociologist Leon Grunberg found that younger generations tended to have a more negative view of unions even though they were members. Indeed, the more strongly these union-member Millennials identified with individualistic statements—checking boxes on the survey that said things like, “I rely on myself most of the time. I rarely rely on others”—the more likely they were to view unions poorly.

My parents’ pensions, for which their organizations fought especially hard, mean that I don’t have to worry about supporting them financially now. That’s made it possible for me to be a journalist, a job for which I had to take less-than-living wages early on. Boeing machinists in Washington state have since lost their traditional pension. My parents’ benefits bought their children’s futures, one in which unions are far less likely to play a role. And yet, I myself was contributing to the generational decline in union membership.

I tried to report my story fairly, but it was hard not to wish the South Carolina workers had unionized so they could be better compensated and build a life like my parents had. But I understood where one electrician, Melanie Holly Lewis Chen, was coming from when she wavered between wanting better pay and worrying about harming the company if a union came in and asked for too much. “I’d rather keep my job than vote for the union and then you get a lot of money and next thing you know you’re laid off,” she said.

Maybe the time of my parents and their union is over. Indeed, in the cul-de-sac where I grew up, some of the houses are owned by other Boeing factory-floor workers my parents’ age. But the new homeowners are software engineers, working in Seattle’s booming technology industry. They’re not unionized either.

—Francie Diep, Staff Writer

PS Picks

PS Picks is a selection of the best things that the magazine’s staff and contributors are reading, watching, or otherwise paying attention to in the worlds of art, politics, and culture.

American Black Film Festival: Since its founding in 1997, the annual American Black Film Festival has become one of the largest festivals for black filmmakers and storytellers, with over 10,000 attendees and more than 1,000 narrative feature films, documentaries, and shorts every year. In past years, the festival gave Girls Trip producer Will Packer and Black Panther director Ryan Coogler their start in the industry. Coogler, for instance, showed his student film, Fig, at the ABFF in 2011, three years before his first feature-length film, Fruitvale Station, would win top prizes at Sundance and Cannes. And recently, the ABFF launched an annual documentary-film development fund with the goal of producing and showcasing underrepresented stories, voices, and perspectives.

Research shows that efforts by the ABFF toward diversifying film are sorely needed. A study released by the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism found that black characters made up only 13.6 percent of characters in films in 2017, a number that hasn’t shifted significantly for the past 10 years. In 2017, actress Viola Davis told Variety that, “even in fabulous roles, [black characters] are still within the confines of being ‘strong,’ ‘a device,’ ‘funny.'” In its commitment to provide a platform for black storytellers, the ABFF plays a crucial role in mending the immense lack of diverse representation in Hollywood, on both sides of the camera.

—Kristina Kutateli, Contributor

Lost Ones: The Pulitzer Prizes were awarded recently. Whenever prestigious awards are given out, I never think about the winners. I always think about the ones that come close, but don’t quite make it. In terms of Pulitzers, any finalist is clearly a great piece of writing—it wouldn’t get there if it weren’t. But, who thinks back to the finalists, instead of the winners? Do these pieces have any less value? Does not being the one winner take away the inherent quality of a top piece of writing, of art? I’d like to think not. If so, a lot of us are in trouble.

This year, the features writing category of the Pulitzers was very strong. Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah’s mesmerizing dive in GQ into the haunting radicalization of Dylann Roof, the terrorist who murdered nine black parishioners in South Carolina’s Emmanuel AME church, is an undeniably deserving winner of the highest honor in journalism. But upon hearing of the winner, I was curious: What about the other pieces up for the top spot? Norimitsu Onishi’s New York Times portrait of two elderly Japanese people readying themselves to die, without family or friends around, is a beautifully sparse piece of writing. These two people live in a sprawling apartment complex that once symbolized the energy and vigor of a young up-and-coming nation, but that now stands as a monument to the isolation of an aging population that has lost all of the connections that moor us to this world. And it poses the most difficult question in this life: When you’re faced with death, what will you hold onto in order to keep going?

—Ian Hurley, Engagement Fellow

PS in the News

A look at where our stories and staff surface in the national conversation.

- Staff writer Tom Jacobs’ piece about study that examined whether the Christian right is actually pushing people away from religion was featured in the Washington Post‘s Happy Hour Round-Up. Jacobs’ other story about how the legalization of pot leads to a decrease in crime was featured in the Aspen Institute’s list of the five best ideas of the day on April 27th.

- The74Million included Elizabeth Weingarten’s story about the importance of teaching gender in international relations classes in its TopSheet rundown of the day’s most important education stories.

- Elizabeth King’s “How White Supremacists Infiltrated Metal” was referenced in this New York Times story about how D.I.Y. metal music has spawned a tight-knit community of headbangers in Queens.

- In the wake of Kanye West’s controversial comments about slavery this week, our piece from 2010, “Of Course the Civil War Was About Slavery,” appeared in a recent Vox piece that traced the insidious history behind the musician’s tweets.

The Conversation

Trump Is Unraveling the Foundational Stitchings of American Scholarship (PSmag.com, February 6th)

- Maybe some scholars are getting all panicky like this article describes, depending on their fields. I’m a historian who focuses on African-American, women’s/gender, and disability history. Look up the phrase “the politics of history.” I’ve always known exactly how underhanded politicians and others will distort and manipulate the past to try to serve their selfish interests today. This is why I became a historian. You’re giving Trump way too much credit here. —Jenifer L. Barclay

What Scientists Are Saying About the EPA’s ‘Secret Science’ Rule (PSmag.com, April 26th)

- I don’t get this one. Why shouldn’t more data be available publically [sic]? After the Flint Water Crisis I want to know what data the EPA is using when making decisions. I thought the ideal standards were that science experiments were reported so as to allow public (peer) scrutiny of experiments. “Proprietary Data” doesn’t sound like it allows anything in the public good. I don’t think anyone reading this website thinks the EPA is headed in a good direction but maybe they got this one right. —Lynn

If you have any thoughts about this newsletter or our work—what you like/didn’t like/want to see more of—you can reach us at premium@psmag.com. If you’re not already, become a premium member by following the button below. As we continue to build out the benefits of a premium membership to Pacific Standard, we want to hear what would be most valuable to you.