They are images for the history books: Hundreds of black-clad protesters amassing on the streets of Washington, D.C.; a smashed Starbucks window; a video of “alt-right” figurehead Richard Spencer getting punched in the face. All illustrate the massive protest that crashed Donald Trump’s inauguration on January 20th, 2017, highlighting tactics popular among antifascist groups.

Since that day, antifascism—commonly called antifa—has become an increasingly popular talking point for political observers and politicians. Coverage has mainly included critical think-pieces and condemnations, some from leading Democrats including Nancy Pelosi, and still more from Republicans. Several pundits have argued antifascism is “morally equivalent” to neo-Nazism. But while the existence of antifa is making news headlines and brewing controversy under the Trump administration, it is, in fact, a decades-old, global pan-leftist movement.

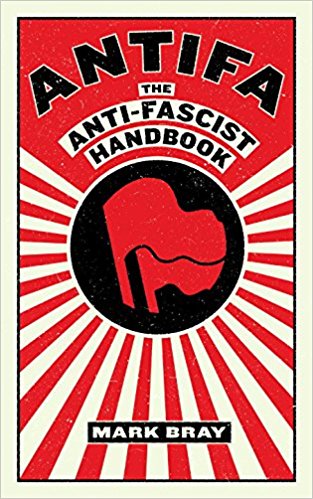

This history, and the present work of antifascists, suggests that the “moral equivalence” critique is misguided, or at least under-informed. In his new book Antifa: The Antifascist Handbook, Mark Bray details the history and goals of the antifascist movement, and includes advice from antifascists to present and future antifas. Bray’s book is positioned above the present back-and-forth in the press over antifa’s merits; it also doesn’t read as a statement in defense of a movement that’s coming under heavy fire. Instead, Antifa, operating under the premise that antifascism is a legitimate and effective movement, immediately reviews antifascist history, theory, and practice.

As the subtitle indicates, the book is a guide of sort for antifascists. This approach reveals a bias that Bray, a historian of human rights, terrorism, and political radicalism, and a lecturer at Dartmouth College, himself acknowledges in the introduction, in which he calls the book an “unabashedly partisan call to arms.” However, Bray’s research will likely prove helpful to those outside the movement who haven’t yet engaged with it on its own terms. In a news cycle saturated with criticisms from non-antifascists, Bray’s book provides what’s largely missing: insight from within the movement itself.

In light of the recent surge in highly visible antifascist activism, Bray spoke with Pacific Standard about what antifa is (and isn’t), antifascist activism that gets overlooked, and common tactics beyond “punching Nazis.”

A lot of people mistakenly refer to antifascism as a political organization. If not a political group, what exactly is antifascism, and who are antifascists?

Correct, antifa is not an organization. And right away I should explain that the antifa I’m referring to is “militant antifascism,” as opposed to official, government antifascism. Following World War II, many European governments considered themselves antifascist institutions in response to the governments that came before them. So in Europe, there’s an interchange between the “official” antifascism of the government, and militant antifascism, which is a politic from below, something anyone can do. So in regards to militant antifascism, if there are neo-Nazis in your neighborhood and you form a group to resist them, you can be the local antifa.

I think the tendency of the mainstream media and society in general to be a little confused about this stems from the fact that people are led to believe that politics is done by institutions, and not by people organizing with their neighbors on a decentralized basis. Even from the far-right perspective, many believe that people are getting paid to do antifascist work. They have conspiracy theories that George Soros is the money behind everything. So the dominant perspective is that political activity must have a hierarchal chain of command, but, for the most part, that’s not the case with militant antifascism.

Where does the current antifascist moment in the United States fit into the broader, global history of antifascism? Is there anything unique about antifascism in the U.S. right now?

What’s different is the importance of organizing against far-right speakers who don’t necessarily have any explicit organizational affiliations, such as Milo Yiannopoulos and Ann Coulter. The campus speaker aspect differs from the typical antifa focus on organizing against fascist groups. But I don’t think you can draw a firm distinction, because, while these speakers aren’t members of far-right groups, their events act as unofficial hubs for local alt-right organizing. So the distinction is not 100 percent different, but I do get a sense that the importance of individual speakers is a bit of a variation.

(Photo: Melville House)

We could also keep in mind the European influence on antifascism in the U.S. From the ’80s into the 2000s, antifascist politics in the U.S. were largely under the auspices of the Anti-Racist Action Network. The Network was modeled after Anti-Fascist Action in Britain, and the ARA used the language of “anti-racism” because they thought it would work better in the American context. But since the late 2000s, the knowledge that American anti-racists have about European models, images, and terminology has increased significantly. After the mid-2000s, many groups such as Rose City Antifa in Portland, Oregon, and NYC Antifa started using European phrases and imagery to a greater extent.

Antifascism has entered the mainstream consciousness largely because of street confrontations with known white supremacist individuals and groups. Beyond these physical tactics, how have and do antifascists address subtler forms of white supremacist activity?

Some of the most difficult antifascist campaigns have been efforts to expose individuals who are part of the subcultural left or progressive milieus for being subtly or closeted racists or anti-Semites, or what have you. Antifascists have to deal with pushback from people who accuse them of indulging in conspiracy theories, taking things out of context, or exaggerating. That work is difficult, but I think incredibly important because history shows that fascists attempt to assume a leftist identity in order to infiltrate the left. These campaigns are the kind of nuanced, difficult projects that often get overlooked when we talk about antifascism.

I’ll add that, especially in Europe, there’s been a recent resurgence of far-right political parties trying to distance themselves from an explicitly neo-Nazi skinhead image, so some antifascists have asked: “Are there certain limitations to militant antifascism? What can we do about political groups like that?” This scenario is leading antifascists to re-assess strategies and tactics. I think very few antifascists believe that militant antifascism is the entirety of the struggle to build a new world. It’s a specific activity catered to a certain type of threat.

Many liberal pundits have criticized antifas for not having long-term goals, or thinking about the big picture. In light of the research for your book, what’s your response to this characterization?

Within antifascism, on one hand you have self-defense, and the direct action of trying to stop the advance of fascist organizing. On the other [hand], you have broader attempts to inoculate the general population against the appeal of fascist politics and to build popular resistance to it. The antifa groups that are very small and not open to the public for fear of infiltration and repression, they tend to deal more with trying to prevent the fascist advance, and in that way it’s more of an explicitly defensive position. But just because someone is part of an antifa group that focuses on the defensive struggle doesn’t mean that they’re not spending other parts of their time building positive social movements. It’s just that you may not know about it.

There are other antifascist formations, both now and in the past, that focus more on inoculating society and building popular movements. One example is the [General Defense Committee] model, which has been used as a formation for a couple years now to frame defense in a way that seeks to address potential threats to the working class. The argument goes that building a powerful workers movement will necessarily entail repression, so why not act before it’s too late? Because that’s the thing with fascism: You don’t wait for it to be too late.

People outside antifa are fixated on physical confrontations between violent white supremacists and antifascist activists, but clearly this isn’t the whole story. What are some common antifa tactics that fall outside the realm of street confrontations with white supremacists?

There are many. One of the most basic elements is research—antifascists are very clear on needing to know one’s opponent and gear one’s message to the specific opponent. This means finding out who the leaders are of a specific group, who their base is, who they’re coordinating with, when and where they meet, and who they’re trying to appeal to. From research we get doxing, which has taken on even more importance in the Internet age. Sometimes, simply letting one’s neighbor or employer know about their affiliation is enough to break a fascist’s will to act on it.

Beyond doxing, there’s a term out of Britain called “jumping the pitch,” which is when antifascist activists preemptively take over a space where fascists plan to meet so the latter group can’t assemble. This tactic doesn’t guarantee that there’s not going to be a confrontation, but sometimes claiming the space is enough to stop a gathering.

I’ve also come across examples of noise protest: making noise around fascists so they can’t be heard. There was a case in Denmark in the ’90s, when there was a Nazi house. And basically the way they drove the Nazis out of this house was by having singing protests every night and it just sort of drove them nuts.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.