In 1983, Marsy Nicholas, a 21-year-old senior at the University of California–Santa Barbara, was shot and killed by her ex-boyfriend, Kerry Michael Conley, just days after she had ended their five-year relationship. That’s often where the public story ends, with the victim’s family left to grieve. But in some ways, that’s just the beginning.

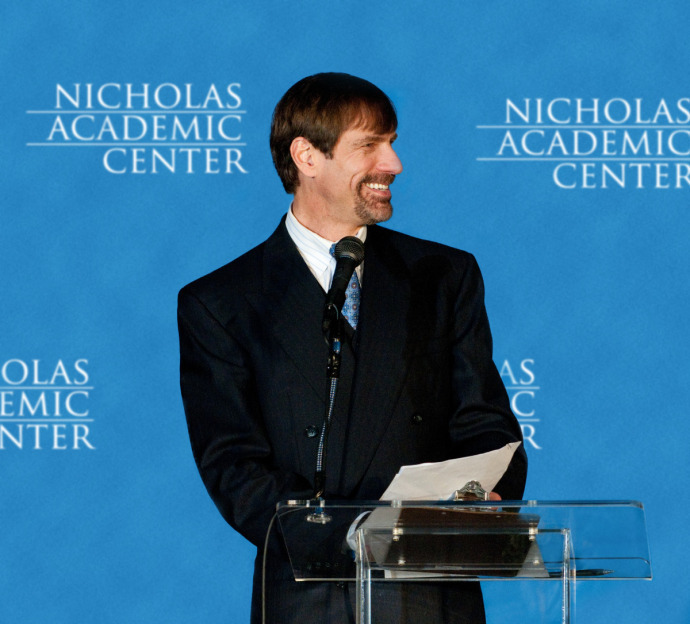

After his sister’s murder, Henry Nicholas went on to co-found a semiconductor company that was eventually acquired for $37 billion. That fortune allowed Nicholas to become one of the foremost victims’ rights activists in the country. He has pumped tens of millions of dollars into campaigns to convince voters around the country to amend their states’ constitutions to include Marsy’s Law, a set of guarantees that looks to put victim and defendant on equal footing. Under Marsy’s Law, states have to notify victims’ families when a defendant is released from custody.

The idea behind Marsy’s Law (also known as the Victims’ Bill of Rights) is that the families of victims should be spared the sort of pain Nicholas and his mother suffered. Just days after Marsy’s death, her mother ran into Conley, Marsy’s ex-boyfriend, at the grocery store. He had been released on bail. She’d been given no notice. Marsy’s Law also mandates that the state notify families of all court proceedings and allow them to testify at those hearings. Many states already have something akin to these rights, but advocates say courts and prosecutors often ignore these guarantees.

There are still other, more novel victims’ rights under Marsy’s Law. After attending Marsy’s killer’s second parole hearing, her mother suffered a heart attack. Under Marsy’s Law, families aren’t just guaranteed the right to participate in the criminal justice system; they are also allowed to shield themselves from it. Under the law, families can refuse to be interviewed by or submit evidence to the accused’s attorneys. The law also expands the traditional definition of victim beyond the individual to their families, and potentially even non-human actors, like corporations. In the case of Marsy’s mother, that could mean staying away from a hearing.

The national Marsy’s Law campaign scored its first victory at the ballot box in 2008 in Nicholas’ home state of California. Voters there supported the amendment by a narrow 8 percent margin. The movement scored its latest victory in November, when Ohio voters approved the constitutional amendment by a 66-percentage point margin. That win came despite opposition not just from the state’s public defenders’ association but also the group representing the state’s prosecutors.

Across the country, the fight over Marsy’s Law has united usually warring factions of the legal community. Proponents of the law say they are simply bringing balance to the criminal justice system by granting victims the same rights that their alleged offenders have, but opponents, which often include civil libertarians and public defenders as well as prosecutors and even some long-standing victims’ rights groups, say the provisions bog down an already overburdened criminal justice system and rob defendants of their right to a fair and speedy trial.

Despite lawsuits and scathing newspaper editorials, the political momentum behind Marsy’s Law seems all but unstoppable. A poll leading up to the Ohio vote suggested wide bipartisan backing. The measure garnered the support of 81 percent of Democrats, 86 percent of Republicans, and 85 percent of Independents—largely because opposing a bill named in honor of a slain woman is political anathema.

In addition to Ohio and California, Marsy’s Law is on the books in both Dakotas as well as in Illinois. Oklahoma voters are set to weigh in this year. According to the Marsy’s Law campaign, similar efforts are underway in Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Nevada, and North Carolina. Campaigners say they would eventually like to amend the federal United States Constitution.

“We can all agree that no rapist should have more rights than the victim. No murderer should be afforded more rights than the victim’s family,” reads the Marsy’s Law campaign website. “While criminals have more than 20 individual rights spelled out in the U.S. Constitution, the surviving family members of murder victims have none.” (The campaign declined to respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.)

Opponents worry the law would further condemn the accused in the jury’s eyes. Alex Rate, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Montana, which successfully challenged the implementation of Marsy’s Law in that state, says Marsy’s Law has the potential to completely upend the American legal system.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

“The notion of due process is a bedrock principle of our nation,” Rate says. “We are talking about removing someone’s liberty. That’s why we have special rights for the accused like due process and the presumption of innocence. I believe in the importance of protecting victims but we cannot expand their rights in ways that infringe on those bedrock principles.”

Rate also has gripes with the fact that Marsy’s Law doesn’t explicitly differentiate between the victims of petty theft and those who have been affected by more serious offenses. Rate says there is nothing in the amendment that would stop lawyers for companies like Walmart from getting involved in the criminal prosecution of petty shoplifting cases.

Meg Garvin, the executive director of the National Crime Victim Law Institute, a non-profit advocacy group based at Lewis & Clark Law School, says current state victims’ rights laws are too often silent on how those rights were to be enforced, which, in effect, means that prosecutors and judges often ignore those rights. Under Marsy’s Law, families can file a motion in court if they feel like their rights as victims have been ignored or railroaded. Garvin adds that concerns about Marsy’s Law are being overblown.

“If a defendant’s lawyer argues that a victim’s right to do something violates the defendant’s rights, the court’s job is to weigh those competing concerns,” she says. “If a defendant’s federal constitutional rights are violated, the victim’s rights lose out at that moment. What these laws do is require courts to be courts and analyze which rights will take priority.”

Currently, prosecutors are tasked with seeking an outcome that produces broad societal benefits—not necessarily the outcome that maximizes benefits for victims or their families. Garvin points out that this hasn’t always been the case.

There were no prosecutors back when the U.S. Constitution was initially ratified. Victims were tasked with proving the criminal case against their alleged offenders, much like in modern civil lawsuits. While Garvin isn’t advocating that we should return to a world without prosecutors, she does believe victims need to be given a more central role in the criminal justice system so that they can advocate for their best interests.

Marsy’s Law opponents counter that, while the existing criminal justice system can rob the people at the very center of tragedies of a seat at the table, some distance between victims and the criminal justice system is essential in order for impartial justice to be meted out. If not, they warn, the desire for vengeance, not rehabilitation, will become even more of a force in the criminal justice system.