Cleveland is dying. Tell you something you don’t know? OK, I will. Cleveland is on the cusp of popping like Pittsburgh. The good news masquerading as bad, United Airlines pulling the plug on the airport hub:

A few decades ago, Hopkins was a fairly busy airport. Not in terms of the numbers at O’Hare in Chicago or Hartsfield in Atlanta or DFW in Texas, but certainly not like some place you always have to change planes to get to. And it was a place that took a lot of pre-planning to get in and out of. I know about this. I drove a cab in Cleveland many years ago.

But the population loss in the region—along with changes in economics and the airlines’ ever-changing business models—has rendered Hopkins International Airport far less busy than it used to be. So when United Airlines announced this week that it was dropping Hopkins as a hub and cancelling about 60 percent of its flights, no one should have been shocked. Nobody there means nobody flying.

But Mayor Franck Jackson and the corporate cheerleaders acted as if United’s actions were indeed shocking. Jackson asked Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine to see if United can really close its hub in Cleveland, and U.S. Representative Jim Renacci (R-Wadworth) blamed United’s decision on the Obama administration. U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) said United’s Cleveland hub was “one of the best in the nation.”

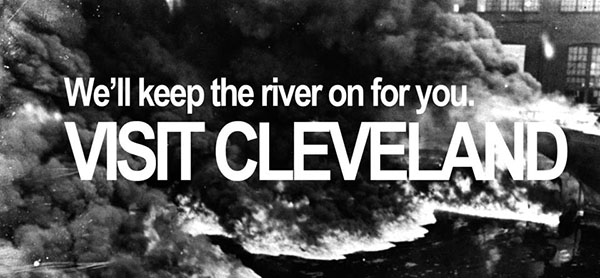

I love political theater, particularly Rust Belt political theater. Kevin Bacon claims all is well while the river is on fire. Hubs are like stadiums. The art of the boondoggle preys on civic pride. Without one, Cleveland is nobody. On the other hand, industry leaders bellyache about the now-doomed regional economy. “United Airlines Ending of Non-Stop to Oklahoma City Could Crimp Ohio Shale Gas Development“:

Oklahoma City-based Chesapeake Energy and other shale gas and oil developers will lose United Airlines nonstop flight to Cleveland this spring. Which means Chesapeake and other Oklahoma-based companies that pioneered Ohio shale gas development will soon be spending more time in the air. …

… Neither Chesapeake nor rival Gulfport Energy would comment about United’s elimination of the service. Depending on the location of their shale operations in Ohio, the companies may also fly employees from Oklahoma City to Pittsburgh or Columbus, but there are no direct flights from Oklahoma City to those cities.

Mike Terry, president of the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association, a trade groups representing Oklahoma-based gas and oil companies, said the dropped United flight is “an inconvenience at best.”

Emphasis added. Journalists suck at geography. Nonetheless, nice of Mike Terry to provide some cover for regional businesses looking for another public handout. Leave it to the politicians to walk that fine line between massaging the bruised Cleveland ego and squeezing out another subsidy for corporate non-stop flights. Now about that geography lesson, another airport in play that didn’t merit mention in the article:

Aubrey McClendon, the embattled CEO of Chesapeake Energy Corp., made an unannounced stop to the Stark campus of Kent State University Wednesday to address about 300 of the company’s Utica shale employees. …

… McClendon arrived at roughly 11:15 a.m. after touching down at the nearby Akron-Canton Airport. The CEO, wearing a white open-collared shirt, stepped out of a black SUV and entered KSU Stark’s University Center, where the meeting was held.

A Chesapeake bus powered by compressed natural gas and diesel fuel was parked outside the University Center for employees to tour.

A disgraced McClendon is no longer with Chesapeake Energy. However, I contend that the Akron-Canton Airport was and still is the landing strip of choice for industry mining the Utica Shale. I know this from firsthand experience. Don’t take my word for it:

Chesapeake Energy’s new regional field office continues to take shape on the city’s south side. …

… Chesapeake’s operations are concentrated in Carroll, but its corporate footprint is in Stark County, particularly downtown Canton and, soon, Louisville.

“I don’t get any impression that anything is getting scaled back,” said David Kaminski, director of energy and public affairs for the Canton Regional Chamber of Commerce.

That bit of news is from September of 2013. The development of the Utica Shale hasn’t panned out as hyped. Perhaps it will in the near future. Regardless, Chesapeake set up shop near the Akron-Canton Airport (CAK). I used to fly direct from Denver to CAK and then take ground transportation to Pittsburgh. I met a few oil workers from Colorado making that commute, which is how I initially learned about the Marcellus Shale boom. I doubt Chesapeake cares one lick about Cleveland’s hub.

I don’t think anyone residing in Northeast Ohio should be concerned. In fact, United’s departure is cause for celebration:

A city doesn’t need an airline hub to build a strong economy. The Pittsburgh story proves that.

But Pittsburgh did what Cleveland’s failed to do: Transitioned from a manufacturing economy to one that also values and rewards ideas, innovation and education.

Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank CEO Sandra Pianalto has cited figures that the country now has 2.5 knowledge-based jobs for every manufacturing job.

Rust Belt cities that meet that benchmark will succeed. Ones that don’t will fail.

Pittsburgh became a “brain hub,” creating 2.9 knowledge jobs for every manufacturing job. Cleveland suffers from brain drain, with a pathetic 1.8 knowledge jobs for every manufacturing job.

Brain hub good. Airport hub irrelevant. That’s true unless you are a shill working for the New American Foundation:

Pittsburgh is another example of a major city whose culture and economy is increasingly determined not by its underlying fundamentals but by the dictates of an ever more concentrated, yet failing, airline industry. After it lost most of its steel industry in the 1970s, the city did everything the apostles of the so-called new economy said must be done to compete in the emerging global economy. When the city played host to the G-20 Summit in 2009, President Obama hailed Pittsburgh’s transformation “from a city of steel to a center for high-tech innovation—including green technology, education and training, and research and development.” That same year Forbes named Pittsburgh one of America’s best cities for job growth, while the Economist lauded its cosmopolitan cultural amenities, such as the topflight Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra and the Pittsburgh Opera.

But Pittsburgh’s renewal as a vibrant, creative, international city is now in doubt, due to the downscaling of its international airport, which now stands largely empty. Pittsburgh International was able to offer more than 600 daily nonstop flights after the city went deeply into debt to turn it into a showcase during the 1990s. But when US Airways merged with America West and concentrated its hub operations in Philadelphia and Charlotte, Pittsburgh service tumbled. US Airways’s daily flights have plunged from 542 to sixty-eight, causing the shuttering of half the gates at the airport as well as sections of two concourses.

K&L Gates, one of the country’s largest law firms, used to hold its firm-wide management meeting near its Pittsburgh headquarters, but after flying in and out of the city became too much trouble, the firm began hosting its meetings outside of New York City and Washington, D.C. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, the biggest employer in the region, reports that its researchers and physicians are increasingly choosing to drive to professional conferences whenever they can. Flying between Pittsburgh and New York or Washington can now easily take a whole day, since most flights have to route through Philadelphia or Charlotte. A recent check on Travelocity showed just two direct flights from Pittsburgh to D.C., each leaving shortly before six in the morning and costing (one week in advance) $498 each way, or approximately $2.62 per mile.

The friendly skies are falling. If anything, the loss of the U.S. Airways hub signaled the start of Pittsburgh’s remarkable turnaround. The story of the hub’s decline is also remarkable. The death knell put an exclamation point after the pejorative, “Shitsburgh.” Pittsburgh hits rock bottom.

U.S. Airways blowing up the fortress hub in Pittsburgh proved to be a burp in the region’s arduous climb out of the dismal ’80s. Besides, the airline had a lot more wrong with it than Pittsburgh did. The doom and gloom obscured the revitalization of the struggling East Liberty neighborhood:

In the late 1990s, Tom Murphy, then Pittsburgh’s mayor, persuaded Home Depot to open a store in East Liberty, starting a retail revival. The city tore down the failed high rises and turned the pedestrian mall back into a street.

About the same time, developer Steve Mosites wanted to attract a high-end grocery store to eastern Pittsburgh, popular with doctors, professors and other well-heeled people. Land prices were too high in the wealthy Shadyside district, so he settled on the fringes of neighboring East Liberty. In 2002, Whole Foods opened a store on a site owned by Mr. Mosites’s family firm. The success of Whole Foods and Home Depot eventually encouraged Trader Joe’s and Target to move into the area.

The shotgun wedding worked. Pittsburgh would plow through the Great Recession along with Texas cities such as Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, and Austin. Losing the airline hub wasn’t a big deal because bigger trends were driving Southwestern Pennsylvania (i.e. brain hub). No one could see that in 2004. Ten years later, no one sees what the coffee cartel is brewing in Cleveland: