For all the dastardly, no-good ideas we see spreading today (jihad, jeggings, kamehameha-ing), it’s reassuring to learn that some genuinely good ideas seem to be catching on, too. Case in point: the growing rejection of domestic violence around the world.

In a study published last week, University of Michigan doctoral student Rachael Pierotti finds that between 2003 and 2008, acceptance of the justifications for domestic violence in 26 different countries—and not just the Luxembourgs and Monacos of the world, but low- and middle-income countries like the Dominican Republic, Zambia, and Cambodia—fell off a cliff.

Pierotti’s study draws from data collected by the USAID-funded Demographic and Health Surveys project. In two separate surveys of over 350,000 women between 15 and 49 (and a smaller subset of male respondents), researchers asked under what circumstances it was OK for a man to beat his wife. “Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things which his wife does,” the survey stated. “In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations?”

1. If she goes out without telling him.

2. If she neglects the children.

3. If she argues with him.

4. If she refuses to have sex with him.

5. If she burns the food.

In general, people in both survey waves were least likely to see burnt food—and most likely to see child neglect—as an excuse for violence. But across the 52 data sets analyzed for this study, an average of 51 percent of respondents rejected all the scenarios. In some countries, the difference in opinion between the times of the first and second surveys (about five years, for most countries) was striking.

The map below indicates the responses among women. Border color corresponds to the percentage of women who rejected domestic violence in the 2008 survey: the lighter the border, the higher the rate of rejection. The fill color for each country, meanwhile, represents the change in opinion between surveys. Orange means the rate of rejection declined, while progressively darker shades of green indicate greater positive changes.

Those orange countries—Indonesia, Madagascar, and Jordan—tend to jump out first. The former, Indonesia, saw the greatest backsliding: 67.3 percent of women rejected all justification for domestic violence in the second survey, down from 72.3 in the first.

Still, the overall percentages for Indonesia and Madagascar beat those for Jordan, which saw a smaller decline between surveys but where only a quarter of women saw no excuse for domestic violence.

The greatest success story, though, was in Nigeria. Granted, only a little over half of women there said they rejected domestic violence in the most recent survey, but that was up 19 percent since the last survey, which was conducted five years earlier.

“I was surprised by how dramatic some of the changes are,” says Pierotti, adding that her study didn’t look at what caused differences in specific countries. “I was expecting them to be in this direction, but a 20 percent change in a span of five years is really big.”

The second map shows the results among men, who made up far fewer of the survey’s respondents (and in fewer countries) but whose numbers are still thought to be nationally representative. The same legend applies here—the lighter the border, the more men rejected intimate partner violence in the second survey; the greener the fill color, the greater the change between surveys.

Madagascar shows up again in this map, with a rate of rejection that fell 17 percent between surveys. But again, countries in sub-Saharan Africa show a marked improvement—especially Benin, Ethiopia, and Kenya.

Pierotti says men’s reactions were more peripheral to this study, but still, she was surprised. “In a majority of the countries, men are more likely than women to reject violence against women,” she says. “Which, based on my American stereotypes, was not my expectation.”

BUT BEYOND SIMPLY THE fact that these opinions are changing, Pierotti is interested in why they’re changing. In the study, she invokes “world society” theory, an observation among scholars that global norms and beliefs tend to produce similar policies and education structures from country to country, even where circumstances and cultures differ dramatically.

“The problems they face might be totally different and the solutions might be fairly different,” Pierotti explains. “And yet we see a lot of sameness.”

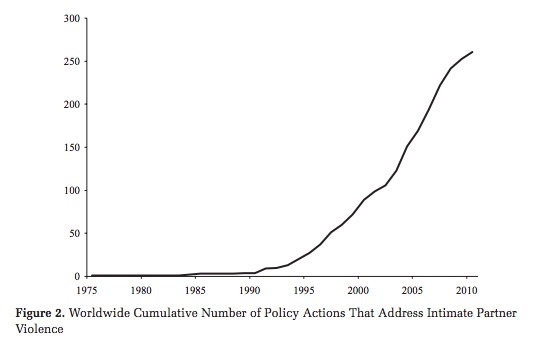

Scholars chalk that up to the influence of big international organizations like the United Nations, but Pierotti says she wanted to push that understanding further to see how movement at the highest levels trickles down through the system to actually change and shape the opinions of average people. Check out this graph, for example:

This shows the number of worldwide policy actions addressing intimate partner violence between 1975 and 2010. See that big upturn in the ’90s and the near-vertical lift since the middle of the 2000s? The fact that individual opinions in many of the countries Pierotti surveyed during that time changed dramatically, she suggests, indicates that those policy actions are actually effective (at least in terms of molding individual opinions)—that they, in essence, cascade all the way down from international campaign to legislature to media coverage to NGO service to school curriculum and law enforcement. And that they do so at a pretty snappy rate.

“Policy makers are by definition elites within their countries, so it’s not as surprising that those elites respond to global pressures,” says Pierotti. “But it is worth looking at whether non-elites face the same pressures.”

Beyond the theoretical questions, though, it’s still difficult to determine why individual opinions are changing in many of these countries (and not in others).

“While people who live in urban areas are more likely to reject violence and people with more education are more likely to reject violence,” Pierotti concluded from the study, “people who lived in rural areas were changing their attitudes just as much. And people with very little education. So when I saw these big changes, I thought it would be due to fact that there have been dramatic increases in education in some of these countries. That explained some of the changes but not most of it.”

“The one other finding that to me was surprising was this is not a change driven by young people. Our stereotypical view of social change is as generations replace each other, attitudes change, and that doesn’t seem to be the case here. People of all ages are changing their attitudes about violence against women. That’s another place where further research is warranted. Why aren’t younger people more likely to reject violence?”

Pierotti also sounds a loud note of caution in interpreting her results.

“I think these changes in attitudes may very well have nothing to do with changes in behavior. In fact, it’s possible that the incidence of violence is increasing, because as people question social norms and assert rights, they can put themselves at risk of violence. So while I agree that these changes in attitudes are heartening, I don’t have anything to say about behavior.”

Still, she’s hopeful.

“I’m not totally convinced that what [survey respondents] deeply believe in their hearts is changing,” she says, “but I do think it’s evidence that the ‘right answer’ is that it’s not OK to beat your wife. And that, to me—that matters.”