(Photo: STR/AFP/Getty Images)

The audio message began with a woman’s voice. “I only have 4 percent [battery] left,” she begins by saying. There are people still trapped in the building, she insists; it’s just a day after the earthquake, but the government has already given up hope for saving them. The government is going to introduce heavy machinery to clear the wreckage at any moment. Tell them not to do it.

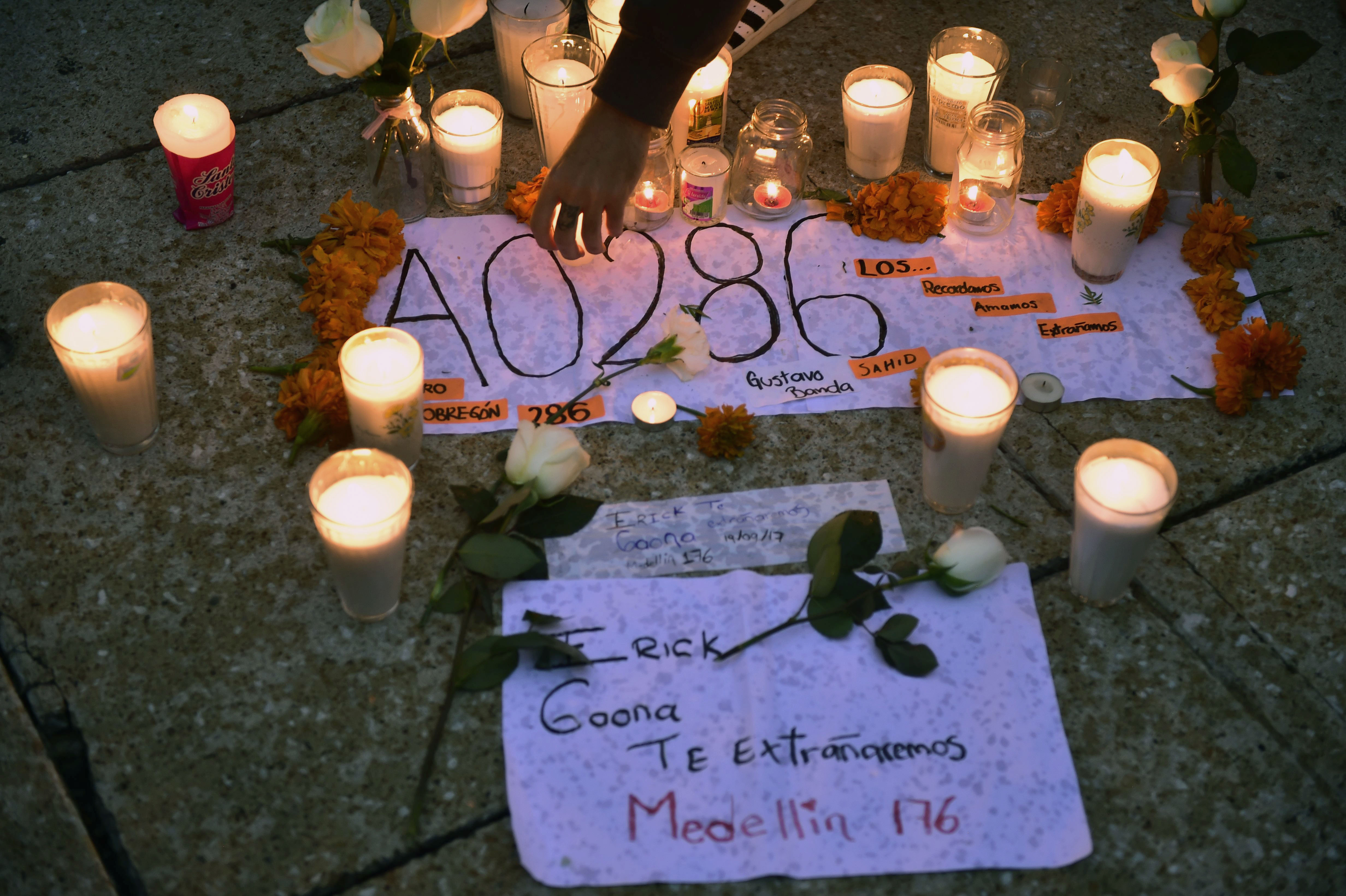

Ernesto Cajja-Maguiña listened to this message while standing outside the ruins of Alvaro Obregon 286 in Mexico City’s Condesa neighborhood. A friend had sent him the recording via social media, a day after the September 19th earthquake, a 7.1 on the Richter scale, had reduced buildings across the city to piles of rubble.

On the eve of the quake, the city listed the official count of destroyed buildings at 30. Families camped outside Alvaro Obregon 286 in tents, waiting to hear from their relatives trapped under the rubble. Rescue brigades—the famous troops of topos, or human moles, that first formed after the 8.1 earthquake on September 19th, 1985, exactly 32 years before this recent disaster—had spent hours burrowing inside the massive pile of concrete.

Anxieties ran high across the city. Viral messages, like the audio of the woman warning that the use of heavy machinery would endanger any survivors, were adding to the panic. Cajja-Maguiña looked around. He was standing in one of the principal disaster zones of the city. He didn’t see any heavy machinery: no bulldozers, no backhoes, no excavators. He approached a topo standing nearby.

“I just got this news,” he explained. “Is this true?”

No, it wasn’t. The rescue workers would have to receive approval days in advance to rule out the possibility of life within the ruins. Cajja-Maguiña began writing on his social networks: It’s not true, he explained. They’re not bringing in machinery on Alvaro Obregon. Don’t spread this information.

The earthquake, whose epicenter was less than 70 miles south of Mexico City, turned the country’s capital upside-down. By the end of the month, the death count in the city had reached 219; the national count stood at 360. In the weeks after the event, schools in affected delegations remained closed as search-and-rescue operations continued in the rubble.

In the days following the earthquake, Mexico City residents volunteered to aid rescue teams and donate goods to victims. They also took to social media to spread information about the disaster’s fallout. The virality of their posts become a double-edged sword. Some used social media to coordinate the vast swaths of volunteers who turned out immediately after the quake. Others propagated rumors that stoked panic. Misinformation reached such a height that the city government issued a warning against spreading non-corroborated information.

On the evening of the earthquake, Melissa Martinez Larrea went out to deliver batteries and food to the rescue teams. She quickly realized, though, that she could do more.

“I started seeing that there were lot of shares on Facebook, retweets, images being sent on WhatsApp that were being spread like wildfire,” she says. “Lots of information wasn’t being refreshed and wasn’t being verified.”

Martinez is a professor of migration at Universidad Anahuac; She has a background in government, and she figured she had the necessary skills to take on the problem: she could communicate, coordinate a team, and verify information. On Wednesday morning, Martinez created the Twitter account @JuntosSismoCDMX.

Along with a team, Martinez received tips, sent volunteers out, or contacted volunteers on-site to verify tips and then posted verified information. The tweets ranged from calls for help to reports of collapses to donation requests:

Edificio en Monclova y Quintana Roo (condesa) se derrumba. 20.09 13:41 pm reportan vecinos.

— Voluntarios (@juntossismocdmx) September 20, 2017

Voluntarios reportan que está saturado de ayuda por el ten ligero Ciudad jardín

— Voluntarios (@juntossismocdmx) September 20, 2017

Frente a los talleres de autobuses estrella. 20.09 13:38

Necesitan medicamentos – intramusculares y antibióticos- cruce Juan Escutia y Nuevo León (Condesa). 20.09 12:45 pm

— Voluntarios (@juntossismocdmx) September 20, 2017

By Thursday morning, they were getting several dozen retweets on each post. Between the Twitter account and the concurrent Facebook page, Martinez’s team reached thousands of people.

In a natural disaster in 2017, even when the power lines are cut, social media allows for every resident with a phone to access a deluge of information, much of it inaccurate. This surfeit of viral information is unique to today’s technological landscape. News and rumors alike proliferate on social networks. In addition to Facebook and Twitter, WhatsApp is particularly notorious as a medium for propagating false information. The fake news that feeds political rancor becomes, in a natural disaster, a question of life or death: Is my building really going to collapse? Will my family be rescued? Is another earthquake going to strike? Do I need to evacuate?

Some of Mexico’s largest media entities spread false information—the nationally owned Televisa station propagated a story about a girl named Frida Sofia trapped in a school, which it later retracted as false. Some Mexico City residents like Martinez found ways to use social media to cut through the chaos. By rigorously verifying the tips they received, they managed to quell panic from behind their phones and computers.

Ariadna Torres considered herself part of the “digital brigades” in the days after the earthquake. She was in her 16th-floor office on Avenida Insurgentes when the earthquake struck. She saw smoke billowing up from collapsed buildings outside the window; Facebook posts gave Torres her first information about collapsed buildings. The night of the earthquake, she stayed at a disaster site until two in the morning. The next day, she joined a friend with a motorcycle to deliver goods across the city wherever they could. Someone had added her to a Facebook chat where people were spreading and checking information.

(Photo: Pedro Pardo/AFP/Getty Images)

With the motorcycle, Torres could cross the city quickly to double-check the information she received. She started posting verified information. Her friends started sharing her posts, then friends of friends, and then people started contacting her.

“I was in touch with people who would ask, ‘Is this true” over here we need this,'” Torres says. “At one point I was in contact with 60, 70 people at once.” She, too, had received the panicked audio message from the woman warning against bringing heavy machinery into the rubble.

Even as volunteers grew savvier about fact-checking, misinformation continued to spread. Cajja-Maguiña lives moments away from the Plaza Condesa concert venue. The day after the earthquake, his girlfriend told him to get away from the area because the plaza was about to collapse. The Reforma newspaper had published something to that effect. While the newspaper El Universal had posted a piece that explained that the Plaza was cordoned off while workers checked for damage, the headline implied that the building’s “collapse [is] feared.” A tweet insisting that civil protection was warning of the building’s collapse received over a thousand retweets.

Ernesto left his apartment, and when he returned the next day to check on his cats, he approached the officials in front of the cordoned plaza. “Everything’s going to fall,” they told him. Ernesto was skeptical. The officials couldn’t tell them where they got the information or point him to their superior. “The soldiers, the information that they had was gossip from Facebook,” Ernesto says.

Instead, Cajja-Maguiña asked a bar owner in Plaza Condesa if the rumors were true. The bar owner immediately told him that reports of imminent collapse were untrue; five experts had already inspected the Plaza and confirmed that there was no structural damage.

Once again, Cajja-Maguiña posted to Facebook to debunk the rumor.