Studies have already shown that kids work as incredibly precise detectors of straight-up lies. Outside the realm of bold-faced falsehoods, though, children perform quite brilliantly, too.

Subtler and more elegant deceit—the kind where the truth is told but other important elements are shaded or concealed—doesn’t go unnoticed by six-year-olds either, according to a new study published in Cognition. Unbeknownst to their teachers and parents, young kids are apparently equipped with the perceptive powers of seasoned Cold War spies. The new paper suggests that they don’t appreciate when they’re being misled with lies of omission and even adjust their behavior based on a previous record of deceit.

In an experiment, developmental psychology researcher Hyowon Gweon and her team had six-year-olds and seven-year-olds rate hand puppet teachers who were introducing Elmo to a toy. Before they watched, they were allowed to play with it themselves.

One toy (henceforth One-Function Toy) had only one functional affordance (twisting a purple knob activated a wind-up mechanism) and the rest of the parts did not depress nor function as buttons. The other toy (Four-Function Toy) looked almost identical, but in addition to the purple knob, the toy had one button that activated LED lights, one that activated a spinning globe, and one that activated music.

The puppet lecturing Elmo about the one-function toy simply demonstrated its single purpose, but the puppet teaching Elmo about the four-function toy only demonstrated the purple knob and left its other three components unexplained. The children didn’t dig witnessing this puppet information gap. “As predicted, children in the Teach 1/4 condition rated the Toy Teacher significantly lower than children in the Teach 1/1 condition,” the authors write. “These results suggest that children are sensitive to under-informative pedagogy. Children understand that a teacher who provides accurate but incomplete information about a toy is less helpful than a teacher who provides accurate and complete information.”

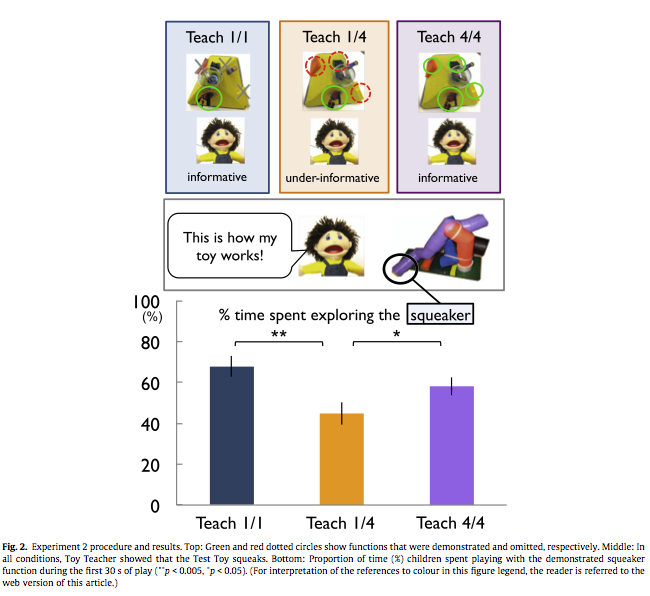

In a second experiment, the team attempted to determine whether the teacher’s track record would affect the amount of time kids spent playing with another toy, a board with multiple colored parts that the puppet demonstrated how to make a squeaking noise with. If they were misled to begin with, the kids would reserve significantly more time inspecting other parts of the board besides the squeaker. “Planned comparisons showed that children in the Teach 1/4 condition spent significantly less time with the squeaker during the first 30 [seconds] than did children in Teach 1/1 condition,” the authors write. “Thus by six years of age, children keep track of others’ informativeness; when an informant’s credibility is in doubt, children engage in compensatory exploration.”

Here’s a visual breakdown:

Bottom-line: Explain the full-fledged functionality of Super Soakers to your kids or risk losing their trust forever.