Thanks to the equality of opportunity provided by sandlots and playgrounds, it used to be axiomatic that an American kid from any neighborhood could rise to the top of any major league sport. No more. For one thing, there are fewer and fewer sandlots and playgrounds. A more important reason is that fewer and fewer parents can afford the escalating costs of organized sports.

Consider this: If Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Magic Johnson, Jim Brown, or Jackie (Flo Jo) Joyner Kersee were born in this century instead of the last, we’d probably never hear of them—their parents didn’t make enough to pay the costs of their kids’ play.

“Free play has disappeared,” says entrepreneur Darryl Hill, who grew up on the streets and playgrounds of Washington, D.C., to become, in 1963 at the University of Maryland, the first African American to play football—or any major sport—in the Atlantic Coast Conference. “There are no more sandlot sports.”

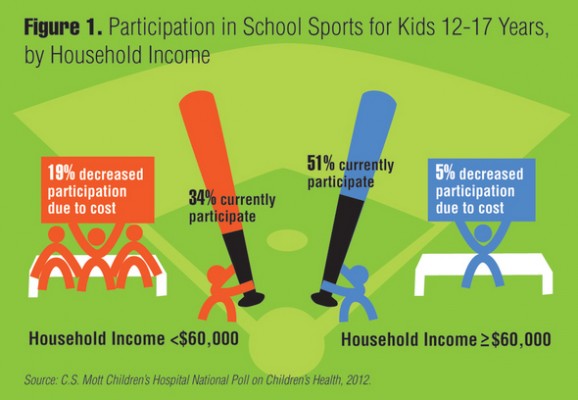

Even school teams are becoming rarer. An examination of who plays youth sports from ESPN The Magazine finds that while there may be 21.5 million kids between age six and 17 playing on a team, including teams at schools, the earliest participants come from upper-income families. “We also see starkly what drives the very earliest action: money,” wrote Bruce Kelley and Carl Carchia. “The biggest indicator of whether kids start young, [sports researcher Don] Sabo found, is whether their parents have a household income of $100,000 or more.” Kids from low-income families are the least likely to be on multiple teams.

“Here’s an astounding statistic: 95 percent of Fortune 500 executives played sports. That speaks to the leadership qualities kids can learn, such as teamwork, cooperation, how to win and how to lose, and how to play by the rules.”

And disturbingly, 3.5 million kids are expected to lose school sports by 2020, especially in financially strapped states like California and Florida and big inner cities: “Living in poor corners of cities culls even more kids from sports. Nationwide, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, only a quarter of eighth- to 12th-graders enrolled in the poorest schools played school sports.”

Cincinnati resident Fran Dicari, host of the website StatsDad.com, talks about the $11,714 he spent on his two children’s equipment, fees, and travel expenses in one year. “Looking back on it, you would not think we were sane people, but in the circle we were in, we were normal.” One father quoted in several studies mentioned his astonishment at realizing his 14-year-old son, a catcher, was lugging around a bat bag containing $2,500 worth of baseball gear.

Let me offer an anecdote from my nephew Tom Greenya, who has a good job as general manager of Country Inn & Suites North in Green Bay, Wisconsin, as does his wife, Debbie, a mechanical engineer. “We have three boys—five, eight, and 11—and they all play baseball, basketball, and one is now into tackle football,” he explains. “There are dues associated with all of those sports. I heard recently that the baseball league is going to stop buying helmets because now all the kids have their own helmets. Back in the day, the league or the playground provided the helmets, but these days every kid has to have his own bat, every kid has to have his own helmet, and not every kid can afford that.”

To counter these cost obstacles, Hill recently founded the Kids Play USA Foundation (“Removing financial barriers to participation in youth sports”). He sees these economic obstacles as harmful both to potential young athletes and to society itself, a view shared by many, but definitely not all, parents.

“Leveling the economic playing field,” Hill says, “is not only good for the kids health-wise and character-wise, but also good for society. An idle kid is a problem about to happen.” He shows a command of data—“In the 1970s, more than 20 percent of African American kids had made it to the major leagues in baseball, but now it is eight percent—and shrinking,” or “One of three [U.S.] kids are overweight or clinically obese by the age of 13, primarily due to decreased physical activity”—to back up his concerns.

Kids Play USA’s main mission, according to its founder, is “to make sports affordable and available to all children, and we will realize that goal by pursuing initiatives on two fronts—increasing public awareness of the problem and chipping down costs. The latter could include having existing groups focus on affordability, helping communities to organize lower-cost sports, bringing in other organizations or corporations to offer direct financial assistance, or even sponsoring ‘free’ teams to play in expensive youth leagues.” Kids Play would also provide free and safe equipment to underserved kids.

Mark Hyman, author of The Most Expensive Game in Town: The Rising Cost of Youth Sports and the Toll on Today’s Families, calls escalating expenses “the global warming of youth sports.” An adjunct professor of sports management at The George Washington University, journalist, and attorney, Hyman’s book is the second of a one-two punch. In Until It Hurts, Hyman wrote about the injures, both physical and psychological, that over-zealous sports parents end up causing their own children.

A poll taken in 2012 shows the impact of rising costs, especially on those least able to pay to play:

Hill told Pacific Standardthat the rationale for his recently formed non-profit crystallized when he noticed, while at a girls’ soccer tournament in Laurel, Maryland, that not one of the 150 kids was black. Thinking it might have something to do with economics—his straight-A’s major in college—Hill asked a manager and was told the tab for each kid was $175 a month “just to be on the team. It has nothing to do with the shoes, the bags, the uniforms, the travel expenses, etc. The total cost including travel could be up to $5,000 a year. So I said, ‘OK I get it. That’s purely economic discrimination. And it’s got to stop.’”

For many families, even those making more than the chart’s $60,000 threshold, the kicker is the travel expense. Says hotelier Greenya: “With baseball, they play twice a week, but if a kid is good enough—and his parents can afford it—there are travel teams and special teams like for weekend tournaments and the different uniforms and the entry fees are all added costs. I’m sure there are kids who would love to do that, but their parents can only scrape up enough money to get into the normal league play.” Those special teams Tom spoke about, so-called travel or club teams, travel to other cities and towns to compete against other “select” teams.

In the last several years, financial journalists, especially those who advise families, have written about the problem. Financial writer Sarah Lorge Butler of CBS MoneyWatchreported in 2011 that one family told her they’d spent $4,000 for their nine-year-old to play on a travel baseball team. And a family with three girls had laid out at least $8,000 a year for club volleyball.

Spurred by Butler’s story, MSN’s Karen Datko wrote: “Girls’ softball can cost $150 per child. That doesn’t take into account the bat, glove, hat and cleats that must be purchased. Youth football can run as much as $400 per child. Soccer, basketball and other sports aren’t far off. Club teams, with the additional hotel and travel costs, are in a league all their own.”

Writing in The New York Times in mid-2012, Mike Tanier warned parents: “If you have not outfitted a little slugger lately, prepare for sticker shock. The youth baseball circular for one major retailer advertises bats in the $219.99 to $249.99 range. There’s a $129.99 glove…. A batting helmet protects tiny heads for $39.99. A pair of Nike Jordan Black Cat cleats … at $51.99…. Batting gloves cost $19.99, and there is no need to worry about Junior getting a hernia from lugging all that precious equipment if you buy a $44.99 wheeled bat bag….”

Expenses aren’t just in fancy equipment. According to Datko, “Some cash-strapped municipalities have turned to charging or raising fees for use of public fields, which means higher costs for the parents of youth team members.” And Tom Geenya reports that “in Wisconsin some cities and schools now charge for the previously-free use of their fields and gymnasiums,” with the problem of escalating costs existing all across the sports spectrum. “That’s how I see it in baseball, and every sport has it. In basketball you hear about the AAU-type tournaments, and the kids travel on weekends. I feel it’s almost too much too soon.”

Nephew Tom, the 42-year-old father of three sons who have many more years to play various sports sees another problem: the parents. “Some people are trying to relive their own playing days through their kids,” he says. Darryl Hill agrees. “Parents have invaded kids’ sports to the point where kids aren’t having fun anymore. Parents have injected themselves so thoroughly that not only has it become commercial, but it has produced a lot of pressure on the kids. The parents are teaching them to win at any cost, which circumvents the necessary roles.”

“When kids are playing among themselves, they police each other: ‘Ah, man, don’t do that! You know that’s not right. You out of bounds.’”

According to Hill, the danger in parental over-involvement is that a child might choose not to play and thus lose out on its many potential benefits. “Kids who play youth sports make better citizens in every measurable capacity,” he says. “They’re more likely to become better students, to graduate and become better, more productive citizens, and less likely to be involved in drugs and violence.

“Here’s an astounding statistic: 95 percent of Fortune 500 company executives played school sports,” he says. “Ninety-five percent. That speaks to the leadership qualities kids can learn, such as teamwork, cooperation, how to win and how to lose, and how to play by the rules—especially if the parents stay out of the process.”

Hill had originally intended to concentrate his foundation’s efforts on the Maryland-Washington-Virginia area, but having seen the extent of the problem he is now seeking the money to go national. A quick scan of academic literature—from Denmark, Australia, Canada, Sweden, some of them places with subsidized assistance—suggests he may want to consider going international, too.

Until then, when Hollywood inevitably remakes the classic baseball fantasy Field of Dreams, the new tagline may be, “If You Build It, They Will Come … If Their Parents Can Afford It.”