It’s a clear summer morning in West Seattle as the sun rises above downtown. Ferries, cars, buses, freighters, and bicycles swirl around the city in chaotic motion. From my vantage point on Alki Beach, backlit skyscrapers look like cardboard cutouts teetering on the edge of the Salish Sea. In the foreground, hundreds of Native people are preparing oceangoing canoes—massive 30- to 50-foot vessels that hold up to two dozen crew-members—for today’s leg of the Tribal Canoe Journey, the annual West Coast voyage that has become one of the largest Native American gatherings in North America. On Alki’s sandy embankment and boardwalk, people haul paddles, coolers, and life vests from vehicles to the canoes.

My sister Zia and I, both clad in Ray-Bans and traditional red cedar bark woven hats, sing a Drake song as we load the day’s necessities onto the canoe named Skookum. Our father stands by, paying us intermittent attention. The last two summers, he and I have journeyed with the Squaxin Island canoe family from the Squaxin Island reservation in Kamilche, Washington. But this marks the first-time the whole NoiseCat clan—a group long separated by miles, divorces, alcoholism, and the simmering but undeniably present intergenerational pain of being Indian—has pulled together to make the voyage. Latching our hands onto Skookum‘s seats, we heave her down to the waterline.

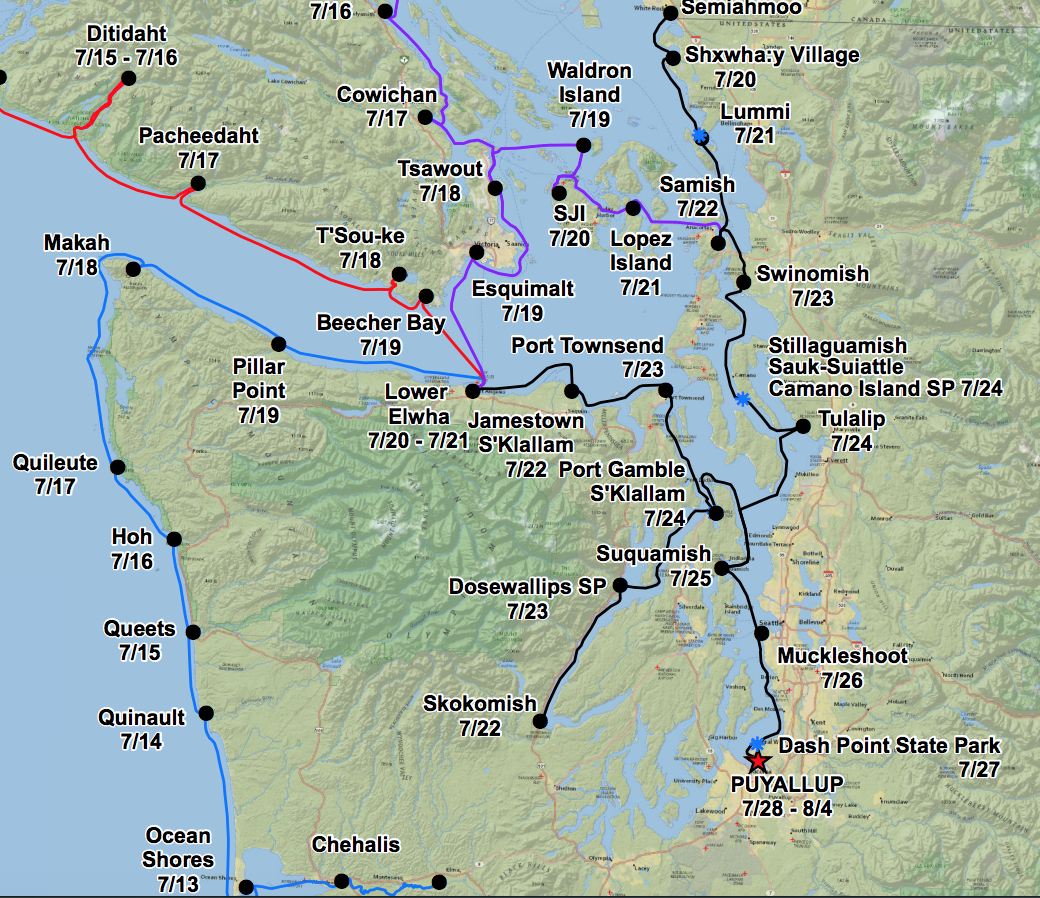

This year, canoes departed from communities as far north as Ditidaht and Snuneymuxw on opposite sides of Vancouver Island and as far south as the Satsop River in Washington’s Olympic Mountains. The furthest sojourners paddled for days through open ocean before entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Salish Sea, pointing their canoes south toward Seattle and the homelands of the Puyallup in Tacoma, Washington, our final port-of-call. There the Puyallup will host thousands for a week of cultural celebration. For the last two weeks of July, the Salish Sea, a network of coastal waterways that fan out like capillaries around northwestern Washington and southwestern British Columbia becomes the stage on which we assert, with our paddles and canoes, the continuity of indigenous presence—past, present, and future—that so few seem willing to see.

(Map: Power Paddle to Puyallup, courtesy of the Puyallup Tribal Council)

In knee-deep water, we board Skookum one by one, shifting in our seats to balance our weight as we fill the craft from bow to stern. Seated in the front of the canoe, I pull out my iPhone and take a selfie of our beaming crew, paddles dipping into glistening water, as we pull away from Seattle. Soon we are heading south, leaving the city behind, bound for Puyallup. Pulling in unison, we join together in Squaxin Island’s humble paddle song to keep time and connect us to the community our vessel represents:

Oh—oh-we-ay-oh

Oh-we-ay-oh-we-oh-way

The voices of my fellow Squaxin Island crewmembers rise up from the seats behind me. On all sides, dozens of canoes glide out into the wide-open Salish Sea.

The morning we depart marks the fourth day that an orca, nicknamed Tahlequah, has made headlines for carrying the corpse of her dead calf with her in a so-called “tour of grief.” Tahlequah’s display of mourning—keeping her lifeless child afloat for thousands of miles, nudging the baby’s body forward with her head—serves as a morbid reminder of the grim outlook for the southern resident orca population: They number just 75 whales and have not seen a single successful birth in three years. Little surprise, then, that the Center for Whale Research estimates the population has a five-year window to reproduce, after which they will fade into memory.

Native people, particularly on Canoe Journey, follow Tahlequah’s story closely. Many Salish consider killer whales kin. The Lummi, whose homelands lie north of Seattle and who paddle their canoe not far ahead of ours, call the charismatic mammals qwe lhol mechen, which means “our relative under the water.”

The bond is spiritual, but it’s also one of shared suffering. Tahlequah’s calf died largely from social forces: fishermen netting her salmon, industry polluting her waters, and ships disrupting her hunting grounds. Indigenous peoples know these grievances—and the struggle to protect food and water from those who would pilfer without hesitation—all too well.

Many Native communities know Tahlequah’s grief. It was not so long ago that experts spoke of Indians the way they speak, today, of the southern resident orcas: as endangered, vanishing, the last of their kind. We indigenous have returned from that catastrophic brink, but the specter of death and disappearance still haunts us. A survey of Native women in Seattle found that 94 percent, or 139 out of 148, were raped or coerced into sex at least once in their lifetime. There is a ghastly trend of indigenous women and girls going missing and turning up murdered across the United States and Canada. At the end of 2017, Native Americans and Alaska Natives made up 1.8 percent of missing cases in the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Crime Information Center database even though they represent just 0.8 percent of the overall population.

As our canoe family strokes cedar paddles through the glistening Salish Sea a few dozen miles south of Tahlequah, we count out “power pulls”: powerful and prayerful strokes for our relations. One for a crew member’s ailing aunt. Two for a grieving family. Three for ourselves.

(Photo: Julian Brave NoiseCat)

I think of my father, Ed, and the target he wears on his back as a muscular Native man with brown skin, long hair, unpaid debts, a criminal record, and the emotional burdens that never leave survivors of abuse, the laughs we share, stories we tell, and art projects we dream-up over marijuana bowls to dull that pain.

I think of Zia, my 17-year-old kid sister, who prefers rock concerts with friends to traditional gatherings with dad and bro, and her becoming in this world.

That night, crew from scores of canoes, numbering more than 1,000 Indians, pitch tents at a campsite in Tacoma. The snowcapped peak of Mount Rainier, known as “Tacoma” or “Tahoma” in Salish Lushootseed language, meaning “Mother of Waters,” for which the city is named, stands tall in the distance.

The next day we paddle into our final destination at the port of Tacoma. Crews dress in their finest regalia. Children, their faces bright with red-earth designs, sit in parents’ laps. Bigger kids paddle. Many crews wear matching shirts and other gear to express affiliation with family, community, and canoe. Almost all wear woven cedar bark hats or headdresses.

(Photo: Julian Brave NoiseCat)

We paddle Skookum up Hylebos waterway on the northernmost edge of the port, passing seafood packers, logistics depots, and shipyards. Puget Sound Energy’s proposed fracked gas terminal, vehemently opposed by the Puyallup but nearly complete, stands across the man-made channel from our final landing site.

Canoes—some hand-hewn from red cedar trees, others fashioned from strips of yellow cedar and still others constructed from more modern materials like carbon fiber, many painted with intricate and distinctive designs depicting ravens, wolves, and killer whales—raft-up in the waterway.

There are 108 distinct canoe communities and societies represented in port today. A delegation of Puyallup chiefs, councilors, and youth leaders stands ashore to welcome us. A crowd of a few hundred has gathered to witness the pageantry.

As each canoe makes its final approach, one representative stands. They speak, first in their indigenous tongue and then in English. Sometimes they share a song. Occasionally they carry a message. A few voice solidarity with the Puyallup in the fight against Puget Sound Energy.

(Photo: Julian Brave NoiseCat)

As is customary, the Puyallup welcome those who have traveled furthest first. Squaxin Island is one of Puyallup’s neighbors. The two tribes even signed the same Medicine Creek Treaty in 1854. We will be one of the last to come ashore. Sitting in the canoe, Skookum‘s crew eats our way through a cooler-full of bananas and cherries. The water acts like a giant mirror reflecting the midsummer sun. My skin burns and begins to peel. It takes the Puyallup more than four hours to get to us.

When it’s our turn, I steady myself before rising. Gripping a cordless microphone, I take a deep breath and enunciate in the Secwepemc language I learned from my kye7e, my grandmother, one of our last fluent speakers. Speaking slowly and earnestly, I invite everyone to join us for next year’s journey to the San Francisco Bay.