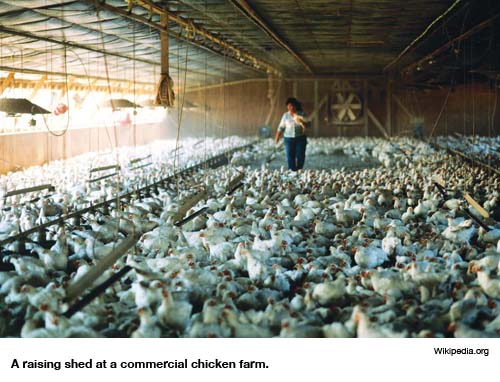

Murray Opsteen has 18,000 chickens at his feet. He’s standing very still, so as not to crush them with his size-12 boots. Although the chickens densely carpet the floor around him — so densely they have little room to move — they aren’t making much noise. In fact, the primary sound in Opsteen’s vast barn, known in the poultry industry as a raising shed, comes from half a dozen powerful electric fans pushing the shed’s fetid air. Still, the air reeks, because the chickens are being raised atop their own excrement, a practice that hugely reduces cleaning costs. “They’re birds,” says Opsteen, a broad-backed giant who doesn’t mince his words after 18 years in the poultry business. “And this is the way birds live.”

Here’s how the process works: A nearby egg hatchery sends chicks to Opsteen’s raising shed just a few days after birth. They’re given another 40 days to mature and fatten in the raising shed, and then they’re trucked away to a slaughterhouse operated by a grocery chain. After they leave, Opsteen scrapes six weeks’ worth of excrement off the shed’s concrete floor. Then the next huge flock of chicks arrives.

To help the birds cope with infections — the shed is forever teeming with the many types of bacteria and parasites that thrive in chicken excrement — drugs are mixed into the birds’ supplies of food and water. Opsteen’s not sure exactly what type of drugs they get; he relies on his feed supplier to get the mix right. But on one specific drug issue, Osteen is extremely clear: Although eggs are routinely injected with antibiotics at many North American poultry hatcheries, this was not done with the chickens on Opsteen’s farm, located in Ontario, Canada.

Opsteen’s uncertainty about the types of drugs used on his farm seems incongruous with his insistence that drugs were not used at the hatchery. But Opsteen, after all, is no ordinary farmer. He’s the farmer assigned to handle reporters looking for farm tours here in Ontario, heartland of the chicken industry in Canada, where exports to the U.S. are booming. And today, Opsteen’s been designated by professional chicken-industry media handlers to deliver one major message: On his farm at least, the chickens come from drug-free eggs. “I’m absolutely certain these chicks came from eggs that were not injected with antibiotics,” he says. “In fact, I can guarantee it.”

It’s a long way from Murray Opsteen’s raising shed to the gleaming, ultramodern headquarters of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration near Baltimore. But Opsteen’s preoccupation with denying the practice of injecting antibiotics into eggs — a procedure widely used to help prevent disease in densely packed chicken raising sheds — follows directly from a directive issued by the FDA last year.

Citing concerns that injecting eggs with antibiotics “presents a risk to the public health,” the FDA issued a rule in July 2008 that severely limited antibiotic use in hatcheries. The aim, the FDA said in a carefully reasoned statement backed by government studies from the U.S., Canada and Europe, was to restrict use of a class of antibiotics due to fears that misuse on farms reduced the antibiotics’ effectiveness for humans — a concern long voiced by the American Medical Association, the World Health Organization and public health agencies in numerous countries.

Coming from a federal agency with sweeping legal powers and powerful law-enforcement capabilities, the FDA’s rule was tough stuff — or so it seemed at first. But that was before the powerful U.S. chicken lobby — sometimes dubbed “Big Chicken” — stepped in. Within weeks of the FDA’s antibiotic prohibition, a barn burner of a fight, pitting scientists against farmers and physicians against veterinarians, ignited across the continent. Then, three weeks before the ban was to go into effect, FDA policymakers — mindful of an earlier ban on antibiotic use in poultry that was won only after years of litigation — suddenly abandoned their own ruling.

The target of the FDA’s concern was a category of antibiotics known as cephalosporins, which are highly valued because of their ability to knock out a wide range of otherwise hard-to-treat human ailments, including urinary tract infections and pneumonia. Cephalosporins were first marketed decades back, but doctors rely increasingly on newer, more powerful generations of cephalosporin antibiotics as bacterial resistance to other heavily used antibiotics — including penicillin — has grown. Although they were long considered a back-of-the-shelf drug, to be used only in rare situations when other antibiotics failed, third-, fourth- and fifth-generation cephalosporins have now moved to medicine’s very forefront.

It was with antibiotic resistance in mind that the FDA announced a ban on certain uses of cephalosporins — most notably their injection into poultry eggs, a practice the FDA had never studied or approved. Unrestricted cephalosporin use “is likely to lead to the emergence of cephalosporin-resistant strains of food-borne bacterial pathogens,” the FDA explained. “If these drug-resistant bacterial strains infect humans, it is likely that cephalosporins will no longer be effective for treating disease in those people.”

Cephalosporins are popular on poultry, cattle and pork farms, where the FDA has approved their use for numerous veterinary purposes. But farmers have also adopted “extra-label” uses of cephalosporins. In one such use, just before the egg hatches, robots pierce the shells of chicken eggs, injecting doses of a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, ceftiofur, to suppress disease.

This practice, known as preventive use, harnesses ceftiofur’s remarkable medicinal power not just to treat infection outbreaks but to suppress them. By preventing outbreaks from occurring in crowded raising sheds that hold as many as 50,000 birds, antibiotic egg injections help chickens to grow faster. The injections also allow farmers to send more birds to slaughter, even while they grow up in their own excrement.

Over the past decade, however, resistance to cephalosporin antibiotics has increased dramatically in North America, Europe and Asia, causing experts, including Robert Moellering of Harvard Medical School, to warn that thanks to misuse of antibiotics by veterinarians and physicians alike “we are perilously close” to not having drugs to treat tough-to-beat infections such as gonorrhea. “There are very few situations where we have no therapeutic options,” Moellering says, noting that eight patients recently died in New York City when cephalosporins and other antibiotics failed, “but we are getting close.”

From the farmer’s perspective, using antibiotics as growth promoters — an approach that U.S. Department of Agriculture antibiotics expert Todd Callaway estimates accounts for half of all drug use on farms — is simply money in the bank. Obviously, widespread agricultural use also greatly benefits ceftiofur’s manufacturer, Pfizer Inc.

And money brings popularity: According to a 2004 study of 24 hatcheries in the Canadian province of Quebec, ceftiofur was injected into eggs in every hatchery studied. In the U.S., according to a summary of a 2001 FDA investigation of 27 chicken and turkey hatcheries obtained by a Chicago-based group, the Food Animal Concerns Trust, four hatcheries reported injecting eggs, while four others reported injecting already-hatched birds. The real extent of ceftiofur usage may have been greater; more than a third of the hatcheries “kept poor or no treatment records,” the FDA reported.

When it comes to tracking drug use on factory farms, says Toni Poole, a USDA specialist on the use of antibiotics, secrecy is a serious problem. Penetrating that secrecy has become an urgent priority for a small but influential group of scientists. Alarmed about the global spread of bacteria resistant to up to as many as 10 types of antibiotics, governments in Europe, Canada and the U.S. established national surveillance systems late in the 1990s in an attempt to track human resistance to antibiotics in relation to usage of antibiotics on farms. What they have found — especially regarding links between ceftiofur use in poultry and human resistance to cephalosporins — has not been welcomed by the meat and poultry industries.

The scientists’ opening salvo came in 2006, when a group of the most senior antibiotic-resistance experts from the FDA, the Public Health Agency of Canada, France’s National Microbiology Laboratory and Belgium’s Veterinary and Agricultural Research Centre warned in a comprehensive review of published data that cephalosporin-resistant bacteria “are frequently recovered from animals and food, with poultry as primary food source, suggesting that humans are often infected by these routes.”

A subsequent series of studies in Europe and North America has convinced researchers — including Frank Aarestrup, a specialist on antibiotic resistance with the Danish Technical University in Copenhagen who helped introduce a system of comprehensive surveillance of veterinary drug use in Denmark — that the link between veterinary antibiotic use and human resistance has been proven. “Taken in context with all the other knowledge we have,” Aarestrup says, “anyone still opposing a link between antibiotic use in food animal production and direct human health impact does so for other reasons than science.”

In a recently published review of international studies on the issue, Aarestrup noted that a Canadian study found the adoption of universal use of ceftiofur in hatcheries in Quebec earlier this decade matched a rapid increase in human resistance to the drug. When this problem was brought to the attention of public health authorities, hatcheries voluntarily stopped using ceftiofur — and there was a rapid decrease in resistance to cephalosporins in humans.

The data cannot conclusively link drug use in poultry with human resistance, says James Johnson, an infectious disease specialist with the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Minneapolis. But like Aarestrup, Johnson thinks the data “is as good as it gets” in terms of signals about the dangers of ceftiofur use in hatcheries. Canadian veterinarians agree: Last year, the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association instructed its members not to use ceftiofur for extra-label purposes such as hatchery injections. The Canadian government also acted, last year ordering Pfizer to include a warning against extra-label use on ceftiofur packages.

Rebecca Irwin, who manages the Canadian farm antibiotic surveillance system, says that strong as the data implicating ceftiofur use in hatcheries with human resistance is, it would be even stronger if the poultry industry weren’t so secretive about drug use. “People can hide behind whatever,” she told a gathering of scientists in early May. “We’re still getting the ‘hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil’ from numerous sources.”

Although chicken farmers seldom discuss their use of drugs — especially high-profile drugs such as cephalosporin — the veterinarians they employ are obliged to be more open, thanks to professional codes requiring at least a degree of scientific transparency. So when it came to mounting a response to the FDA’s prohibition of extra-label use of cephalosporins on farms, the industry turned to the American Veterinary Medical Association. The AVMA represents 78,000 veterinarians working in private and corporate practice, the government, industry, academia and the military.

In a toughly worded, 18-page letter drafted by a panel of veterinarians employed on chicken farms across the U.S., the AVMA broke ranks with its Canadian counterpart veterinarian organization, arguing that the FDA’s rule against extra-label cephalosporin use was completely unjustified. The Canadian, American and European studies cited by the FDA fail to directly demonstrate that veterinary use of ceftiofur impairs human medicine, the AVMA insists, and the FDA prohibition would put animals at risk. “Because veterinarians have a relatively limited number of FDA-approved drugs for treatment of the numerous animal species,” the American veterinarians’ group said, “extra-label cephalosporin use is medically necessary to relieve animal pain and suffering and allow veterinarians discretion to use drugs judiciously.”

Just weeks after the group filed its protest, the FDA reversed course. Late in November 2008, amid a crescendo of last-minute regulatory interventions by the outgoing Bush administration, William Flynn, acting director of the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine, announced the restrictions on cephalosporin use were being withdrawn to allow the agency to “fully consider” comments, including the AVMA’s. “We responded through the AVMA,” says the National Chicken Council‘s Steve Pretanick. “They worked up the argument as to why the FDA should not take this action. As a result, the FDA withdrew it. And that’s the last I’ve heard of it.”

In Pretanick’s account, the business of getting the FDA to knuckle under sounds like a routine event. But Margaret Mellon, head of the food and environment program for the Washington-based Union of Concerned Scientists, describes a “take no prisoners attitude” on the part of the chicken industry at a time when it knew it could count on the White House.

“The past administration didn’t believe in regulation,” Mellon says. But she also believes the FDA itself “miscalculated the blowback” from the industry and its powerful rural political allies.

The FDA now refuses to discuss the matter. But speaking to scientists in Kansas in May, Flynn suggested the FDA’s retreat may not be permanent. The agency, he said, may try again to reintroduce restrictions sometime soon. Until that happens, however, poultry farmers will remain free to play chicken with some of the most important antibiotics in human medicine.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.