Observers of Congress frequently blame party polarization for gridlock. The notion seems a pretty straightforward one: If the parties are ideologically far apart from each other, it’s harder to broker the compromises that are often vital to legislative work. What’s more, the minority party will see any work by the majority as hostile to its interests and beliefs and will work even harder to undermine the majority’s work in a polarized system. Observers can point to plenty of evidence that, as Congress has gotten more polarized, it has become less productive, facing gridlock on more and more of its agenda.

Yet we see a different story at the state level: Several states—particularly Colorado—continue to provide examples of legislatures that can actually be quite productive even while the parties are deeply divided.

Colorado’s legislature just finished its 2019 session a few weeks ago. Media coverage suggests it was a highly productive session, with Democrats, who took unified control of the government following the 2018 elections, delivering on most of their campaigning agenda. These achievements included one of new Governor Jared Polis’ top priorities, full-day kindergarten, along with some criminal justice reform laws, new regulations of the oil and gas industry, a controversial “red flag” law preventing some gun purchases, a ban on gay conversion therapy, and more.

Notably, the state’s productivity wasn’t just a result of Democrats taking control of both chambers of the statehouse. As I noted last year and the year before that, Colorado had very productive sessions then, even while Republicans controlled the Senate and Democrats the House of Representatives. But this year appears to have outdone all prior.

The productivity strikes some as surprising given that, as Boris Shor’s research shows, Colorado also has the most polarized legislature in the nation, a claim it took from California a few years ago. Colorado’s Republicans and Democrats vote more differently from each other than partisans in any other state, even while remaining, for the most part, remarkably civil. (This was well in evidence at a recent panel discussion with state legislative leaders hosted by the Center on American Politics at the University of Denver.)

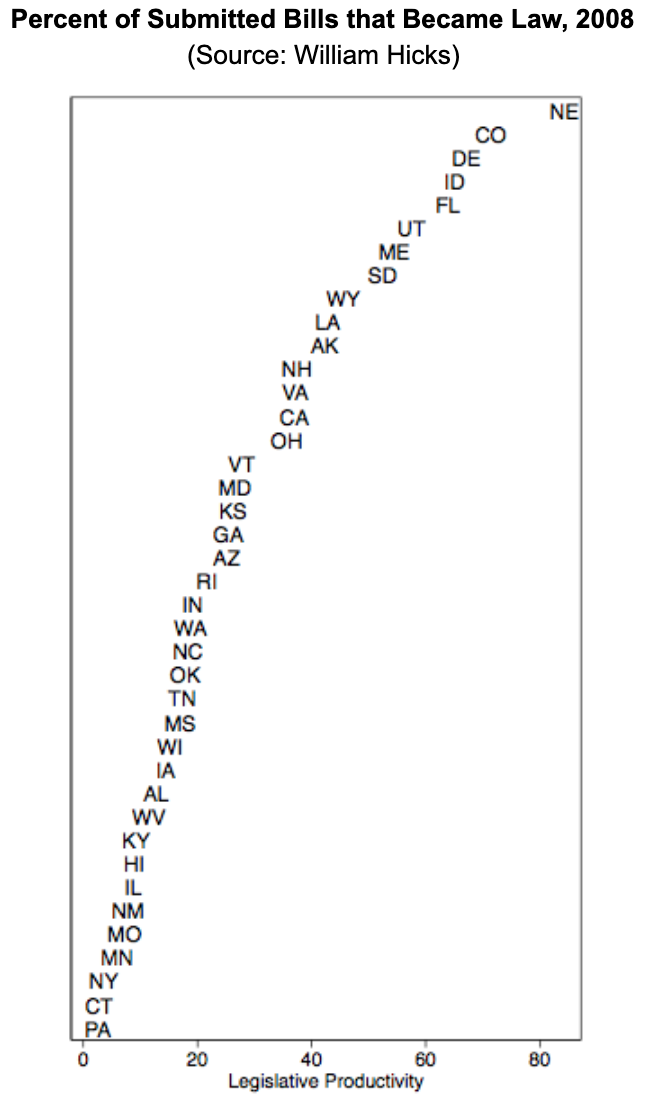

The legislature typically enacts 50 to 70 percent of the bills introduced. According to data collected by political scientist William Hicks, Colorado regularly has one of the highest bill enactment rates in the nation, usually only surpassed by Nebraska (whose legislature has one chamber and zero parties). This year, 654 bills were introduced, and a record 513 (78 percent) have either become law or are awaiting the governor’s signature. Polis still has several weeks to decide their fates, but it’s looking like one of the highest productivity rates on record for Colorado.

How is a polarized chamber able to get so much work done?

One of the most comprehensive works on legislative productivity comes from an unpublished manuscript by Hicks and Daniel Smith, who examined a range of factors and their impact on productivity. What makes for a more productive legislature? They found four main factors:

- Term Limits: A term limited legislature typically has a quarter to a third of its members who are lame ducks and thus spend less time on campaigning and fundraising. This frees them up to do more lawmaking.

- Ballot Initiatives: Direct democracy can compel legislatures to be more productive, either in response to voter-initiated laws or as a way to head them off.

- Same-Party Control: When the same party controls both chambers of the legislature, the legislature is usually able to get more work done. (Note that 49 states currently have same-party control—the highest number in over a century.)

- Amateur or Citizen Legislatures: Those chambers that meet only a few months out of the year and have poorly compensated members and few staff members actually seem to get a higher percentage of their bills passed.

Another feature that may help with this apparent productivity is the limits on the number of bills legislators may submit. Roughly half the states, including Colorado, have such limits. If you can limit the number of bills submitted, that makes the chamber appear more productive.

And what seems to work against productivity?

- Interest Group Organization: Where lobbyists are better organized and resourced, they are usually able to prevent more legislative action.

- Gubernatorial Power: When governors are stronger, legislatures tend to be weaker and less able to push through an agenda.

Hicks and Smith find that polarization does not appear to undermine productivity in any consistent way. To the contrary, more polarized states are slightly more productive, in part because the majority party tends to be more ideologically coherent and has a more specific governing agenda in a polarized system.

If you examine the Colorado statehouse under this framework, it has term limits, ballot initiatives, and same-party control, and is an amateur legislature with limits on bill submissions. Meanwhile, its interest group organization and gubernatorial powers are at the medium levels of their respective scales. That is, Colorado has all the features associated with high productivity and few of the features associated with low productivity. We should expect it to be productive.

Notably, focusing on a state’s productivity doesn’t really tell us much about the quality of the work it’s doing. Several states have shown a remarkable degree of efficiency in producing anti-abortion laws in the last few weeks. And if you’re a Colorado Republican, the state legislature’s recent work probably doesn’t look great, for the most part.

But at least one complaint of legislatures, especially Congress, is that members always bicker and never get anything done. A glance at some states reminds us that this needn’t be the case.