A Death on Diamond Mountain: A True Story of Obsession, Madness, and the Path to Enlightenment

Scott Carney

Gotham Books

In February 2012, Christie McNally and her husband, Ian Thorson, retreated to a cave in the high desert of Arizona for a session of intense meditation. They drank only rainwater, and they ate sparingly. They refused to filter their water—preferring to purify it with their minds. And they became violently ill. McNally recovered and kept meditating, but Thorson fell unconscious. McNally waited two days to summon help, but by then Thorson was beyond rescue. The official cause of death was dehydration, but what killed Ian Thorson was a spiritual quest gone terribly wrong.

How Thorson arrived at his tragic end is the subject of Scott Carney’s A Death on Diamond Mountain, a powerful investigation into the appeal—and the dangers—of enlightenment as understood by Thorson and more than a million other American Buddhists. Since the late 1800s, Americans have been collecting religious wisdom from around the world and seeking alternative spiritual paths. The legacy of those movements lives on in today’s spiritual seekers, who, like Thorson, were inspired by the 1960s counterculture to turn to Eastern wisdom.

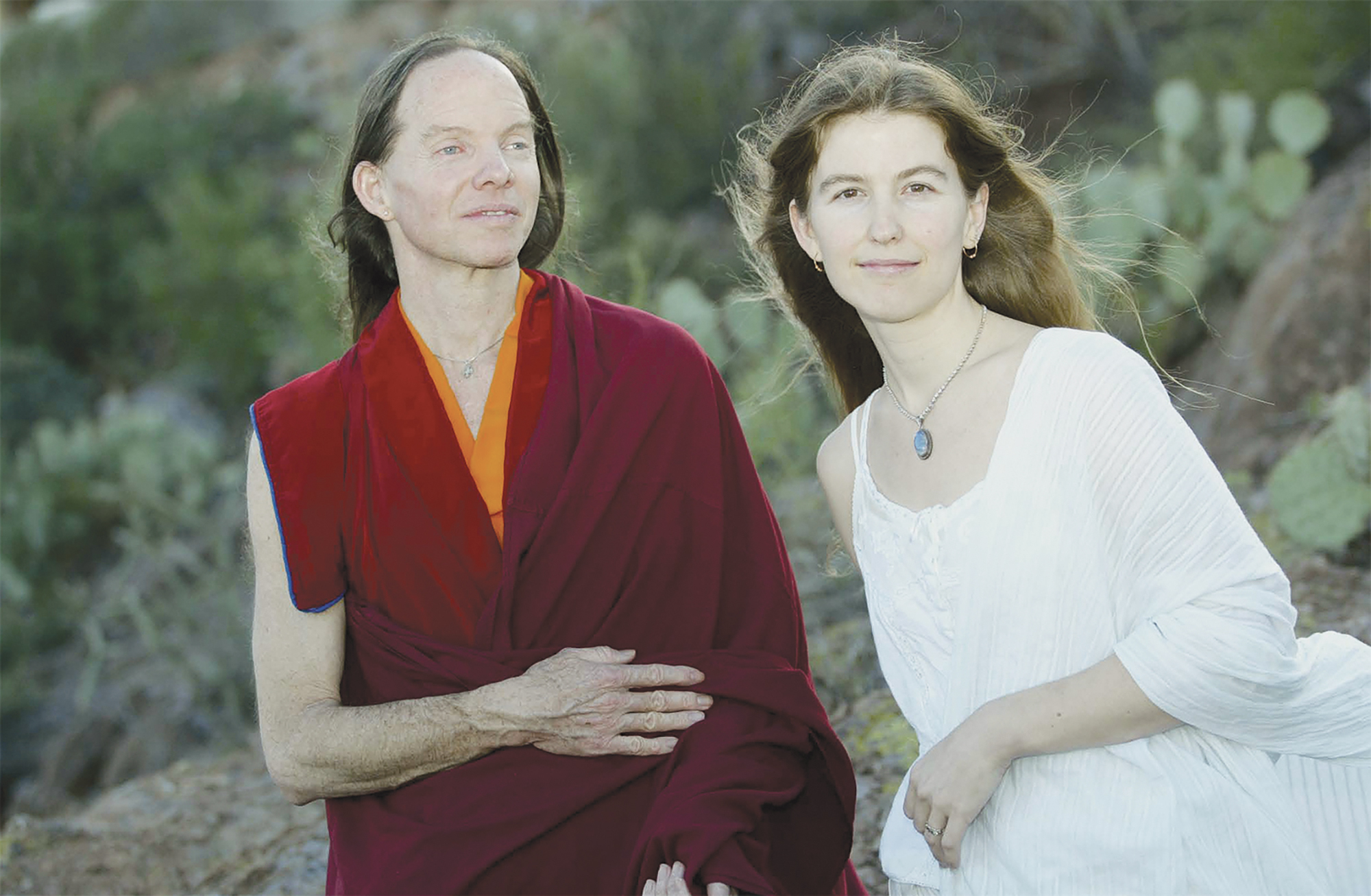

Carney, an anthropologist and journalist, focuses on three people connected by the quest for enlightenment. The first is Thorson’s teacher, Michael Roach. Trained in a monastery in New Jersey, Roach was the first American awarded the title of geshe, the Tibetan Buddhist equivalent of a Ph.D. Roach traveled throughout India, made a fortune trading diamonds to raise money for Tibetan Buddhist organizations, and taught courses on Buddhism in New York in the 1990s, where he met Ian Thorson. As a scholar, Roach’s contributions were considerable—he founded an archive of Buddhist writings when the Chinese government was eradicating Tibetan Buddhism—but he rebelled against the religion’s leadership, and the Dalai Lama denounced him for disobedience.

The second figure is Christie McNally, Roach’s ex-wife, whom Roach had ordained as a lama, or Buddhist priest, and eventually proclaimed the incarnation of a Tantric goddess. McNally divorced Roach after his numerous affairs became public, and married Thorson, a sensitive Stanford graduate and one of Roach’s prize students. After her re-marriage, McNally stayed on as a retreat leader at Roach’s Buddhist facility in the Arizona desert. Her ways were unorthodox. At one point she stabbed Thorson, allegedly to teach him a spiritual lesson about being in a relationship with someone more powerful than himself. The center’s board expelled her, but she stuck around in the desert with Thorson to finish their meditation, living in a cave on federal land nearby. Thorson died there two months later.

It would be easy to dismiss this bizarre soap opera as a simple case of three confused New Agers whose quests got tragically out of hand. Carney, however, is a sympathetic and insightful writer about new religions and their history, and the book yields insights into religious psychology, sociology, and history that go beyond the struggles of his main characters.

McNally and Thorson were high-stakes meditators. They took vows to act as guides and teachers for others, even after they themselves had achieved enlightenment. Their commitment would end only after every other being became enlightened, too—even if this took many lifetimes. Thorson was attracted by promises of happiness, ancient and timeless wisdom, and a spiritual humanitarian mission. So when McNally saw her husband dying of dysentery, she had to decide whether to call for help or to trust him to heal his bad karma spiritually. If he failed to do so in this life, she believed, he’d have another chance in the next, or the one after that.

These people were in pivotal moments in their lives and vulnerable to Roach. Thorson and McNally saw Roach as an embodiment of contentment, purpose, and perhaps magical power. At least since Jonestown, Americans have harbored deep paranoia about religious charismatics with outsize personalities, especially when the religion they preach is not mainstream Christianity. In this case the paranoia seems merited. Roach mixed “timeless wisdom” with formidable marketing to establish his legitimacy and persuade Thorson to treat him as infallible and to surrender autonomy for the promise of a happier, better eternity. Thorson’s gentle pursuit of happiness snowballed into something else entirely.

Gurus, some dangerous, have been around for years, and Roach is no Jim Jones. But much of the forbidden, obscure, and esoteric knowledge that once made Buddhism and other religions difficult to study has now become accessible—with potentially dangerous results. Practitioners of Tantra, a form of magic that promises the fastest path to enlightenment, have long considered it dangerous in the hands of novices. Now Roach’s digital archive brings hundreds of thousands of pages on Tantra to the masses. This is the spiritual equivalent of giving every teen driver a Formula 1 racing car: It’ll go fast, but many young innocents will end up splattered on the road. The tragedy of Thorson’s death appears to involve a spiritual tradition taken out of context and practiced zealously, without any of the warnings or moderating influence that would have accompanied it before.

The decontextualization involved in learning a religion through DVDs or YouTube videos makes it easy to ignore, for example, the complicated nature of the spread of Buddhism to Tibet—a bloody tale that is more Game of Thrones than A People’s History. Western “converts” to Buddhism are often accused of meditating too intensely, as if it were a job or sport. The benefits of meditation are reported constantly in popular media, but few beginners know about the maladies that afflict overzealous meditators. Carney lists a few: restlessness, sleeplessness, and Kundalini syndrome, an uncontrollable oscillation between ecstasy and rage.

Carney ends with his own evolving fears of Roach. As public condemnation of Roach grew, lamas in Tibet offered Carney a protection spell. Carney declined it, and swiftly he was beset by misfortune. Wasps buzzed around him, he grew sick, and his marriage began to fall apart. Carney doesn’t say whether he thinks his experiences were coincidence elevated by paranoia or the product of real karmic magic. But his experience shows how potent spirituality can be, even for wised-up outsiders attempting to study it impartially. Hokum or not, this stuff is anything but harmless.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psmag.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity, and may be published in any medium.

For more from Pacific Standard on the science of society, and to support our work, sign up for our email newsletter and subscribe to our bimonthly magazine, where this piece originally appeared. Digital editions are available in the App Store (iPad) and on Zinio (Android, iPad, PC/MAC, iPhone, and Win8), Amazon, and Google Play (Android).