When the anti-diversity memo by (now former) Google employee James Damore went viral, all I could think of was medieval brewing. In the memo, Damore argued that women as a gender just aren’t as mentally fit as men to be good programmers. Appropriately, the rebuttals to Damore have focused on two issues. First, he’s wrong on the science. Second, he ignores the specific history of coding and gender. Both critiques are accurate and important. As a historian, though, I’d like us to broaden the discussion away from technology and the last 50 years, and recognize that the exclusion of women from coding fits perfectly into centuries of labor history. It turns out that, whenever an occupation becomes profitable, women get cut out.

Damore seems to have bought into the conclusions of the worst kinds of evolutionary psychology. As a discipline, “evopsych” too often depends on inventing biological explanations for observed reality, rather than considering influences from culture and society. In the memo, Damore argues that “science” shows men are evolved to be more suited to computer programing. Science, of course, shows nothing of the sort. People who actually study the neuroscience of gender disagree with Damore’s conclusions. Moreover, as many folks quickly pointed out, women were the first coders. Programming was initially regarded as an extension of secretarial work, but men took over when the profession’s status (and pay) began to rise. “Computer girls” were replaced by “computer geeks” thanks to social factors, not biological ones. So much for Damore’s ideas.

The gradual exclusion of women from coding is not a modern story. Instead, it’s just one of the more recent manifestations of what historian Judith Bennett calls the “patriarchal equilibrium.” Essentially, Bennett argues that, while women’s experiences change, their status generally remains stuck behind that of men. Bennett has elaborated this idea through decades of work on medieval brewing, textile production, and other areas that reveal gendered hierarchies in medieval and early-modern society.

Take brewing. In 14th-century England, women did most of the brewing, as Bennett first explores in a 1986 article on the village alewife. These brewsters made ale, which spoiled quickly after the cask was broached, so they would keep some for their family and sell the rest. Often, the small profits from these sales would enable them to buy ale, in turn, from other women while they waited to make a new batch. But then beer arrived in England from the Low Countries. Thanks to the preservative power of hops, it could be brewed and sold at commercial scale. The village alewife was gradually replaced by larger and larger brewing enterprises, requiring access to capital. Although there were exceptions, men had much easier access to capital than women. By the end of the 15th century, men dominated medieval English brewing.

One could tell a similar story about weaving, only in reverse. In the 14th century, weaving was a high-status, high-profit trade. Most weavers were men. Industrialization turned weavers into a lower-status occupation, so early-modern textile weavers in factories were generally women. It would be a mistake, as Bennett argues in her book History Matters, to merely observe the change in occupation—women become weavers—and thereby argue that women’s material or cultural status had improved. Change in occupation, she writes, does not mean transformation of status.

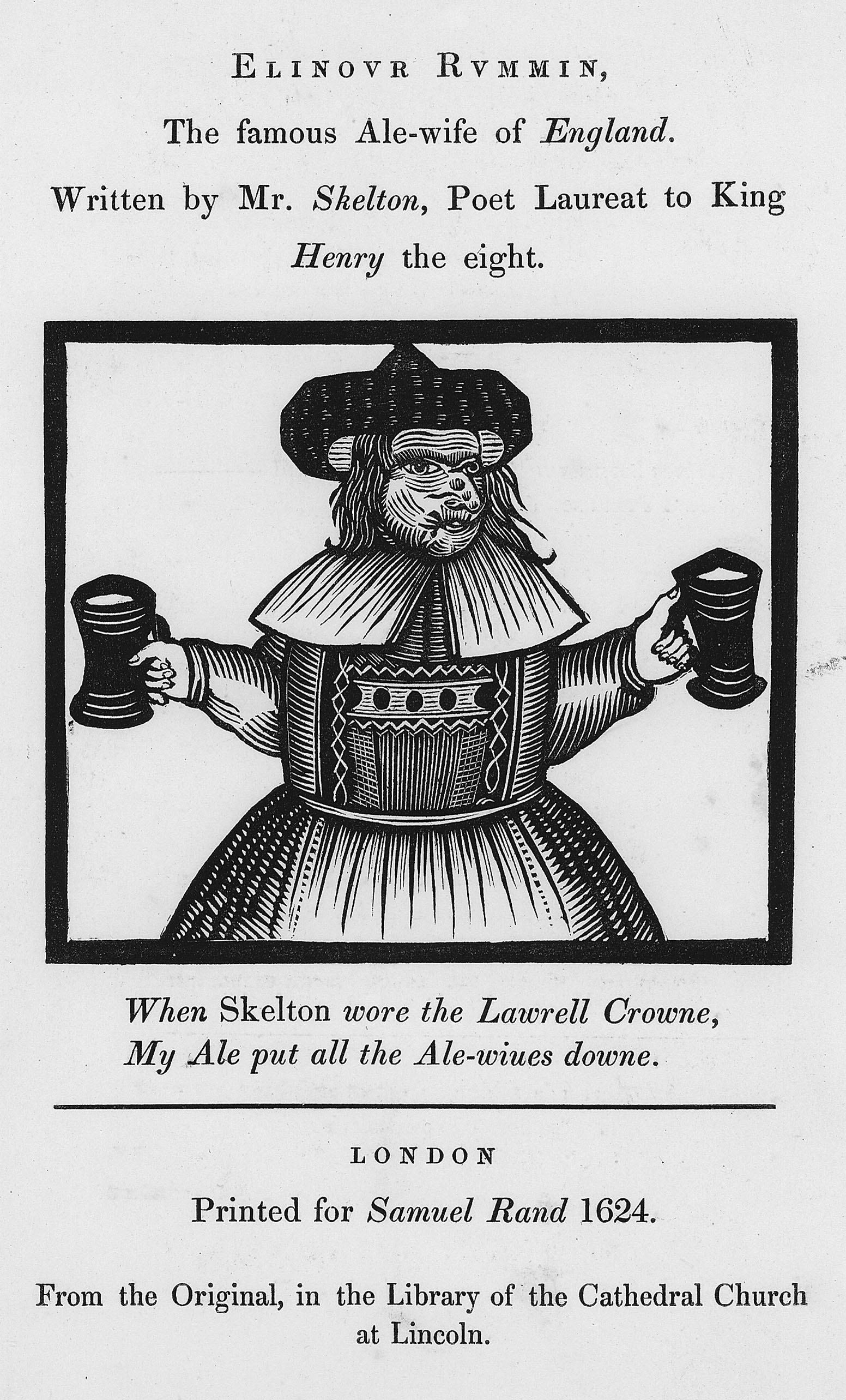

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In Bennett’s account, then, the “patriarchal equilibrium” is the continual social phenomenon of devaluing of women’s work, and devaluing women in other ways, even as technology and conditions of life change. The mechanisms by which better jobs go to men vary case by case and era by era, but the outcome is consistent.

When the Google story broke, I emailed Bennett to ask for her reactions. She wasn’t at all surprised: “This coding story is an old story—in employment and so much else, power moves toward power. The shocking thing about coding-and-gender is that it is such a dramatic version of that old story, and that it happened on our watch.” Bennett recalls that, during the late 1980s and ’90s, feminist scholars were talking about the rising gender imbalance in computer programing even as it took place. As she wrote to me, “We know this pattern; we can now discern it early; and we’ve not yet figured out how to stop it.”

So why can’t we stop it? Bennett suggests that we need to move past the kinds of simplistic explanations proposed by Damore—and she says we also need to move past the idea that pervasive gender inequality is inevitably a simple function of deliberate discrimination. In any given case, multiple factors come together to make patriarchal equilibrium “so damned sticky.” She explains, “PE [patriarchal equilibrium] involves much more than jobs and labor.” Culture, family, law, politics, and more all shape the opportunities for women.

Bennett suggests that gender inequality in tech, for example, emerges of out factors including generalized misogyny (think Gamergate), hyper-sexualization of girls that discourages investment in technological training, and even the oddly masculine “categorization of coders as ‘nerds.'”

Back to brewing—the craft beer revolution of the last few decades has provided opportunities for women to enter the industry, despite the modern cultural associations of beer with manliness. The Pink Boots society, an organization dedicated to supporting women in the beer industry, has been growing over the last decade. But patriarchal equilibrium is rearing its head in that industry as well, not because individual men are driving out individual women, but because Big Beer is attacking Craft Beer. Right now, Anheuser-Busch InBev, the beer giant, is purchasing craft breweries. There’s not a single woman on its management team.

Want to untangle those sticky webs? Along with diversity initiatives, neuropsych debunking evopsych, and a lot of political activism, we need to understand how contemporary problems fit into the past. It’s too easy to look at just programming, which feels so modern, and focus on the details of the computer industry alone. In fact, we need to fight against gender inequality across society, not letting anyone off the hook (including Google), but also not pretending Google is some kind of isolated case. Want to diversify STEM? Start by reading more history.