The American West is a testament to hubris. We beat back the desert with a complex plumbing system of dams, canals, and pumps to create a thriving civilization in the hottest and driest region of the country. But today it’s becoming clear that many of the structures built to prevent a shortage of water have ultimately contributed to its scarcity. And, now, even as we try to come up with new ways to engineer the environment in our favor, the desert is pushing back into its former territory.

Glen Canyon Dam

In the middle of the desert in northern Arizona, the glossy blue waters of Lake Powell pool behind the smooth concrete arch of Glen Canyon Dam. Completed in 1963, this marvel of engineering turned the Colorado River around on itself and flooded nearly 200 miles of the region’s red canyons and gorges. Much like thousands of other dams built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Glen Canyon Dam was constructed to help the burgeoning West conserve its scarce supply of water.

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

But it turns out that an uncovered reservoir in the desert is not the best way to stockpile water—some 123 billion gallons of water seep into the cracks and crevices in the canyon beneath the lake every year, and even more evaporates away into the air. Rising temperatures and a proliferation of dams upstream have also conspired to reduce the amount of water that flows into the reservoir in the first place, so the lake and the amount of electricity the dam produces have been shrinking for nearly two decades. Though environmental groups are advocating for the restoration of a free-flowing river through Glen Canyon, the Bureau of Reclamation signed an agreement last year extending its management of the dam and Lake Powell through 2036.

Navajo Generating Station

Three miles south of Lake Powell, three smokestacks at the Navajo Generating Station rise 775 feet into the air, where they release plumes of toxic exhaust. The coal-fired plant—the largest in the Western United States and one of the nation’s biggest polluters—has blanketed the Southwest in a haze of carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxide, and heavy metals since it began operating in 1974. For decades, the plant ran 24 hours a day, consuming up to 15 tons of coal a minute to drive a set of pumps that siphoned water from the Colorado River and carried it to parched desert cities like Phoenix and Tucson. In the process, the plant itself, run jointly by the Bureau of Reclamation and a collection of public utilities companies, sucked up roughly nine billion gallons of water a year from Lake Powell.

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

The facility’s closure, slated for 2019, is a response to basic economics rather than to environmental hazards: Natural gas is simply a cheaper alternative to coal. The shuttering, while celebrated by environmentalists, will wound local economies. Ninety percent of the more than 900 employees that run the plant and its nearby infrastructure are Native American.

Navajo Sand Dunes

In wet years, the sand dunes that blanket a third of Navajo Nation—some 27,000 square miles of Native American territory in Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico—host a layer of thriving vegetation and remain relatively motionless. But during the region’s inevitable dry spells and droughts—like the one that has dragged on in the American Southwest for the last 16 years—the grasses and flowers wither away, and the sand becomes mobile. Recently, the dunes have begun advancing as much as 115 feet a year, burying roads, houses, and anything else in their paths.

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

The communities have tried pushing the sand back with bulldozers and using grids of clay-based seed cakes, which promote the vegetation that helps keep the dunes in place. But they may be postponing the inevitable. Arizona is one of the fastest-warming states in the nation, and the sand will almost certainly continue to encroach.

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

Biosphere 2

In the late 1980s, construction began on a three-acre glass structure in Oracle, Arizona, where scientists hoped to create a self-sustaining system known as Biosphere 2 (the first being the one that the rest of us inhabit). Four men and four women lived in the facility—a prototype for a future Mars colony, with an artificial ocean, desert, rain forest, and farmland—for two years. The crew could not keep carbon dioxide levels from rising to dangerous levels in the artificial atmosphere, and, after the team was forced to add oxygen to the environment, the project was deemed a failure.

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

Before we can create habitable colonies on other planets, we need to understand how the one we have works. Today, Biosphere 2 is a University of Arizona-owned laboratory for Earth systems studies.

(Photos: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

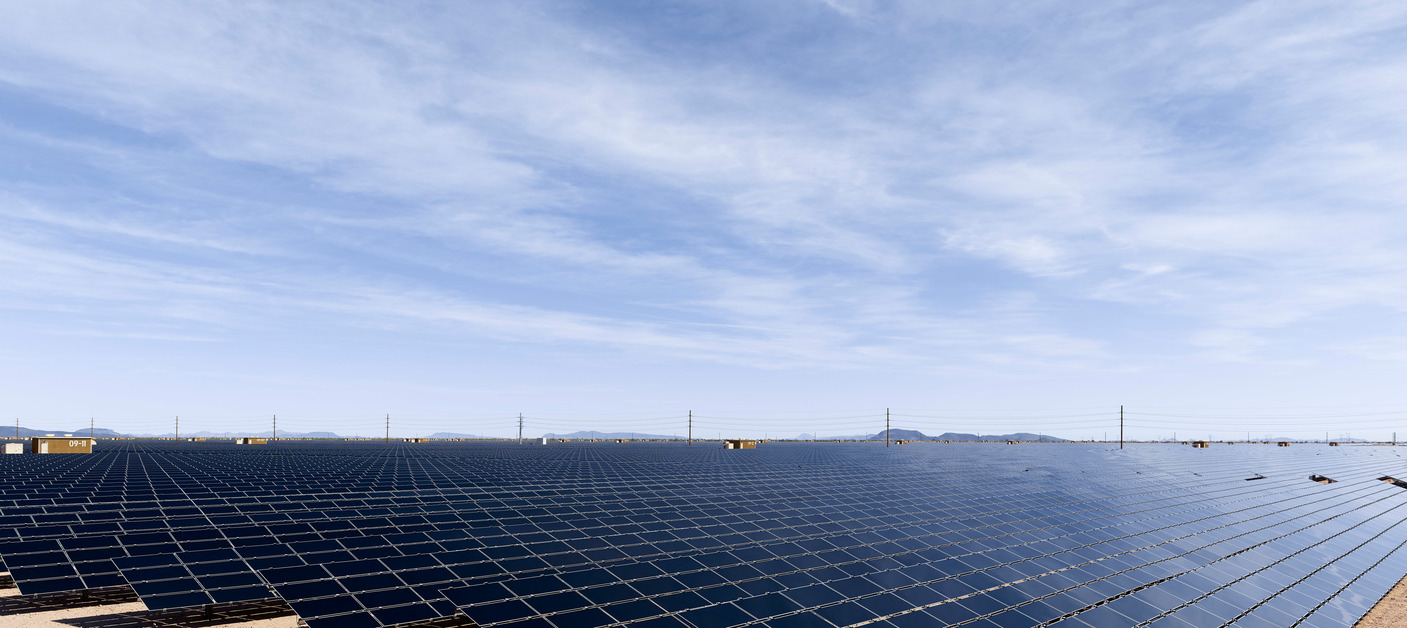

Agua Caliente Solar Facility

Of course, there is at least one abundant resource in the desert, and humans are finally learning to harness it efficiently. The Agua Caliente solar plant—a Department of Energy-funded facility owned by NRG Solar and MidAmerican Renewables—sits on 2,400 acres of desert near Yuma, Arizona, and contains more than five million individual solar panels. The project, which started feeding the grid in 2014, is expected to eliminate some 5.5 million metric tons of carbon emissions over 25 years.

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

Without the emissions cuts laid out in the Paris Agreement, however, climate projections show that rising temperatures and drying soils (coupled with explosive population growth) will drain the West’s water resources, making a decades-long megadrought almost inevitable. More sunny days may be a good thing for groves of solar panels, but that energy won’t matter if the region runs out of water and can’t produce food.

(Photo: Mark Power/Magnum Photos)

A version of this story originally appeared in the July 2017 issue of Pacific Standard, which was produced in partnership with Magnum Photos.