Today is the Fourth of July, a federal holiday commemorating the United States’ adoption of the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

As the country faces challenges, both moral and economic, Americans are tasked with confronting the evolving nature of national identity and what it includes and excludes. As we continue to expand upon that definition, here’s a look at some stories that provide a broader look at the United States, from its fringes to its center:

(Photos: Bryan Anton; Styling: Raul Guerrero)

Born Identity: One Soldier’s Story of Transition

During her transition, Jennifer completed a college degree in finance, and, after her discharge, she became a financial advisor. In 2013, she joined her local VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars). Most of the members had done a tour or two. She was among the few career soldiers, and, in 2014, she was elected the post’s first female commander in its 91-year history. No one at the VFW knew she was transgender

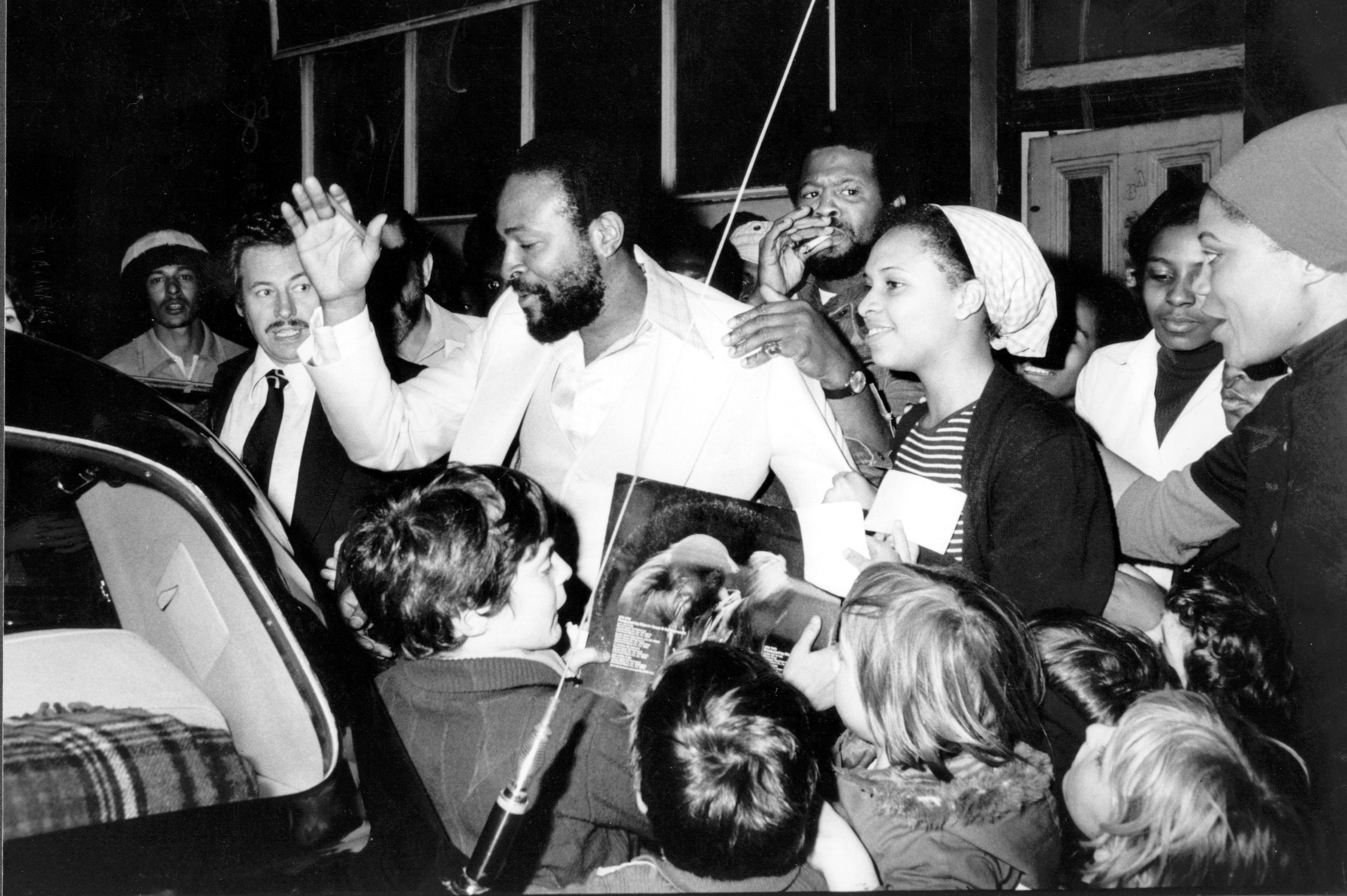

(Photo: John Minihan/Getty Images)

Marvin Gaye and the Unlikely Patriotism of Resistance

When Marvin Gaye sang the National Anthem at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game, he knew he was going to die soon. Rehearsals had been rocky. People feared that he wouldn’t be on time to sing. He arrived late to the arena, disheveled and anxious. He wore a dark suit and oversized sunglasses to cover his bloodshot eyes. His voice trembled on the first line. By the time Marvin got to “…bombs bursting in air…” you could see his hands finally stop shaking. A rhythmic clap began to grow from the audience. By the last lines of the song, the entire crowd had joined in, clapping on beat with Marvin, breaking decorum to honor such brilliance. No one I know remembers who won the game.

No Country for Jailed Men

If you want to know a place, talk to the public defenders. When reporters and photographers from all over the nation flocked to the streets of Ferguson and Baltimore to cover the grief and protests over the killings of Michael Brown and Freddie Gray, the articles they filed became kindling for the slow-burning national conversation about the meaning and value of justice.

The Making of a Mexican American Dream

Undoubtedly the success of future generations of immigrants is dependent on education and immigration reform. It is equally dependent, however, on a shift in the way we talk about immigrants — no longer depicting them as “illegals,” as a problem to be solved, as a threatening underclass. It depends on the willingness of white Americans to break down the monolith of white cultural myths and assumptions, to be seen as well as to see.

The Legacy of the American Diner

If there’s a counter with stools, if people are consuming sandwiches, coffee, and eggs over music that sounds like it belongs in your uncle’s garage, and especially if the linoleum counters boast a layer of grease that will outlive us all, then it’s probably a diner—even if it calls itself a café. To paraphrase a waitress I once knew: A diner is a diner is a diner.

(Photo: John Lingan)

‘Sick at Heart:’ The Lonely Radicalism of the Catonsville Nine

The point of this kind of protest, like the Catonsville Nine’s or the peaceful marches in Baltimore or Ferguson, is to show how flimsy authority really is. An evil flag can be taken down quickly, regardless of cowardly appeals to proper process. A wall of officers with military-grade weaponry can be gently overwhelmed by unarmed citizens. A military draft can be disrupted by nine people with a couple of trashcans. In all these scenes, moral indignation and righteousness are more important than actual concrete goals. The point is to reach minds, to shine a light, and to appeal to outsiders’ sense of right and wrong—their sense of patriotism.

(Photo: Jorge Moro/Shutterstock)

Which Was the Most American War?

To determine what qualifies a war as “most American,” you have to know what “American” means, and I don’t. Not really. How to comprehend not only centuries of blood and genocide and slavery but also real hope, real progress? And how to reconcile their interconnectedness—that hope, that progress, is so often contingent on those same acts of theft, enslavement, and genocide? Then, presuming you have a grasp on what “American” even means, how do you quantify it?

You can find more of our coverage surrounding the Fourth of July here.