For over a century, technology companies have peddled sophisticated solutions to liberate housewives, but when the tech fails to fulfill its promises, women are left to clean up the mess.

By Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite

“Decorate with G-E bulbs — $1.16 a room!” General Electric advertisement in

Life

, January 21, 1957. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Home-based technology remains the way of the future. For its first-ever Super Bowl advertisement, Amazon this year released a commercial for Echo, its new smart-home system designed to help customers make their houses more efficient, more intuitive, and — if Alec Baldwin is to be believed — way more fun. Last year, another smart-house system, Google’s Nest, released its second block of video advertising, shot from the perspective of the homes in which the products are installed. The tagline for the campaign: “Welcome to the magic of home.”

A survey of women readers of Better Homes and Gardens echoes this optimism, with 67 percent of respondents under 35 saying smart technology saves them time, and 55 percent saying that the technology was “easy to maintain and upgrade.”

Nest’s house-based advertising came a year after the company’s first marketing campaign, which featured a grandpa, a toddler, a dad, and a dog, all engaging with the Nest system. There’s no woman in the ads, the implication being that the unseen mother was the one who set it up in the first place. In fact, Nest’s ad campaigns are part of a long history of marketing these products as family-friendly items approved by the traditional domestic decision-maker: mom. Yet Dr. Yolande Strengers, a research fellow in the Centre for Urban Research at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, says that, throughout the 20th century, “new domestic technologies entering the home (like vacuum cleaners, washing machines, and irons) have increased expectations of cleanliness, and that burden has been disproportionately felt by women because they still do most of the housework.” As recently as 2014, the American Time Use Survey found that women do two hours and nine minutes of housework per day, compared to men’s average of one hour and 22 minutes.

Women suddenly had a new job: to master the technologies sold to them, lest they raise their family improperly and somehow lose the Cold War.

In other words, with the promise of smart-home systems’ innovation, ease, and excitement comes the fear that these technologies may be harming us — or, at the very least, that they’re not delivering on the promise of a perfectly engineered home.

It’s crucial for tech companies to win the trust of women consumers in order to effectively sell products, but the cycle of new domestic technology is yet another domestic bait-and-switch: Tell women they’re finally the decision-makers, offer them cutting-edge tech, then berate them for misusing it.

For more than a hundred years, advertisers have marketed technologies to women as tools for individual empowerment and family happiness, combining the promise of individual consumer choice with the language of patriotism and familial duty. In 1891, Alice Gordon, wife of electrical engineer James Gordon, wrote a book called Decorative Electricity, in which she instructed Britain’s trendsetters to adopt electric light in their homes as an aesthetic component of their décor:

We must divide our electric lights into two classes, the practical and the decorative. I shall try in the following pages to give some hints as to the arrangement and the economical burning of the practical lights, and also some suggestions as to what we must aim at, and what we must avoid, if we wish to electrically decorate our houses successfully.

Gordon extols the virtues of electricity as offering effective tools for decorating and modernizing a home with an eye toward upward mobility, allowing Gordon’s majority-woman audience to exercise control over their space.

Decorative Electricity demonstrated that the key to making consumers comfortable with electric light lay not with the men who were creating the networks of wires that crisscrossed cities, but with women, who were considered the primary consumers and household accountants of middle-class Victorian households. This was a useful pitch for an electric future, written by the wife of a high-powered electrical engineer with a considerable stake in the era’s energy revolution. With a housewife’s seal of approval, electric companies and their advertisers posited, a family could rest assured that electricity was a safe product for home use. At the same time, marketing tech products directly to women as tools for building a modern home created a sense of purpose for the middle-class Victorian woman, even as she remained confined to domesticity.

Bringing household appliances into the modern American home of the 1950s was presented in advertising as both a patriotic duty and a matter of personal empowerment for women consumers. The message from advertisers to white middle-class women was that they should get the same fulfillment from household management and childrearing as anyone did from paid work outside the home. By 1960, this practice was firmly entrenched in advertising strategy: “[A woman] wants to put her new talents to good use around the home, she wants to feel that she is employing all those facilities which would be called to play in an outside career,” consumer researcher Ernest Dichter wrote that year in the consumer behavior book Strategic Desire. Dichter was consulting on advertisements for automated kitchen productsdesigned to respond to a person’s needs, but his methods can be seen in the smart-home technology ads of today: The only difference is that today’s smart-home systems are built to both respond to and anticipate needs (even when we don’t ask them to), and the best housewife is the one who knows enough to trust a smart-home system with her family’s well-being.

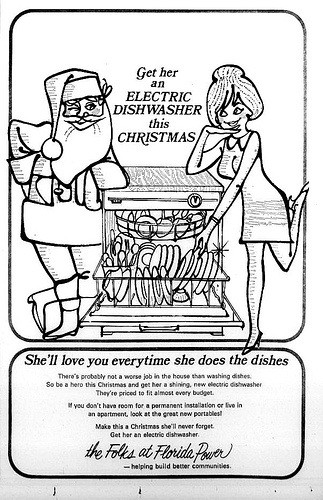

Florida Power advertisement, Christmas, 1969. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

These products claimed they would free women from the banalities of housework, but, as Ruth Schwartz Cowan argues in More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology From the Open Hearth to the Microwave, such was almost never the case. Instead, women had a new job: to master the technologies sold to them, lest they raise their family improperly and somehow lose the Cold War. Automated dishwashers and electric can openers were sold as efficient products for perfect housewifery as well as a way to flex American technological muscle on the home front. Without these products, the ads implied, women wouldn’t be reaching their full potential as modern wives, mothers, and contributing members of a tech-obsessed society.

Advertisers also encouraged women to learn about the mechanics of the products they were buying, so they would be better equipped to fix them if anything went awry with new machines at home. One of the most important home technologies to emerge at this time was the television. By 1955, televisions were present in 65 percent of American households, a huge jump from 1946, when only 0.02 percent of households reported television ownership. In order to incorporate this new machine into the physical space of the house, companies like Panasonic and Motorolapromoted TVs as an integral component of family life — a 1950 Motorola ad in Life even ran under the tagline “TV adds so much to family happiness.”

But while advertisements from television companies emphasized the benefits of a new machine in the house, women’s magazines like House Beautiful and Better Homes and Gardens flip-flopped on whether new technologies were actually beneficial to a home, and women were also expected to master the mechanics of the product and ensure that it fit seamlessly into the existing household architecture and activities.

Features in Life magazine in 1954 raised concerns about schoolchildren spending too much time in front of the TV instead of reading, and, by 1970, the same publication highlighted the psychological correlations between Americans’ obsession with violence and the amount of TV children were watching. In these cases, and in others where a new technology didn’t work as intended, the wife would be responsible for rectifying the situation, forced to work harder to control a tech product that was supposed to make her life easier and better. It’s an ongoing cycle that sociologist Dr. Judy Wacjman writes about in her 2015 book Pressed for Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism, in which “domestic technologies have dramatically transformed our daily lives, [but] they have not met the challenge of keeping home,” including the social responsibilities of maintaining family unity and safety.

The automatic processes of programming the coffeemaker, unlocking an iPad with a fingerprint, or even turning on the light when you get home are the result of years of marketing that create a household problem (your home is too dark, your family too far-flung, your food insufficiently inventive), solves it with a new product, and leaves women to clean up the mess when the technology fails to deliver on its promises — the true cycle of capitalism.

It’s possible that this may change as smart homes evolve; in her research on smart homes, Strengers finds that men are more likely to be responsible for the “technology work” of maintaining and upgrading smart-home systems. “When something breaks down,” she says, “it seems to be men who step in to fix the problem.” To that end, she says, “as men’s leisure time is getting squeezed by changes in the home, smart technology offers to alleviate some of this added burden.”

But the unequal division of labor at home persists, despite these potential developments. In Pressed for Time, Wacjman writes that “the space-age design effort [behind the smart home] is directed to a technological fix rather than engineering a less gendered allocation of housework and a better balance between working time and family time.” Today, more women work outside the home, leaving less time to do that housework to new and impossible standards of cleanliness and Instagram perfection. And if those duties weren’t hard enough to fulfill, pop culture and scientific literature never fail to remind us that, despite our best efforts, these miracle technologies can end up making life harder.

In their advertisements throughout the past century, tech companies have called on empowerment, agency, and obligation to sell their products to generations of women as beneficial products for family unity, safety, and happiness. The promises of an end to household drudgery, togetherness, and security in an uncertain world are rarely realized. Instead, television is blamed for violence among children, radiation from microwaves might be killing us, and smart alarm systems could be hacked at any time. The celebrity-endorsed Echo can order you a pizza with a voice command, but these products still spark suspicion when it comes to privacy and data collection.

“The jury is still out on whether smart technologies save people time in their homes,” Strengers says. “It’s easier to turn multiple things on and off at the same time, but there is often a plethora of more devices and functionalities to choose from.” When these home tech products lose their sheen and are viewed as possibly dangerous, women are expectedto supervise screen time, revive the home-cooked meal, and constantly monitor the devices that were supposed to make their lives easier and their homes safer. It’s an old trick that promises women a quick fix for the impossible problem of an imperfect home, re-imagined for a digital age.

||