Last week, new research was published that showed the first objective recording of the contents from a dream. Using an MRI machine and images from the Internet, researchers in Kyoto, Japan, devised a way to decode with some accuracy what people were visualizing while they slept.

But scientists and science fiction folk alike have been targeting the elusive dream for capture since at least the 1920s. The cover of the September 1926 issue of Science and Invention magazine included concept art of the “dream recorder” machine. The device wasn’t invented by sci-fi publishing pioneer Hugo Gernsback, but his use of it was unique. The “dream recorder” depicted on the magazine was actually just a polygraph machine, which was relatively new at the time.

Gernsback must have had some terrible nightmares throughout his life, because, according to him, there is absolutely no such thing as a good dream. Dreams, he insisted, were harmful to one’s well being and could actually kill. His Science and Invention article is riddled with warnings about the danger of our ethereal bedtime companions: “Any one with a weak heart, therefore, should never indulge in heavy food before going to sleep, whether it be an afternoon nap, or the night sleep. If he does, a fatality may result, directly due to a dream.”

Well, OK then.

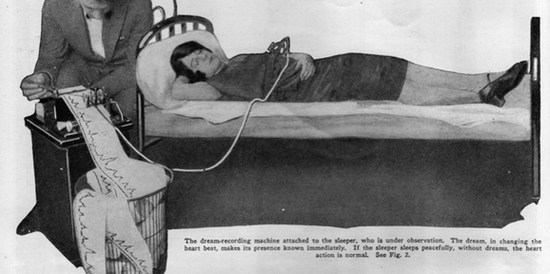

A “dream recorder” in action (1926).

But Gernsback didn’t stop there:

The person who sleeps best, and is most refreshed by sleep, is that person who does not dream. The term “pleasant dreams” should be abolished. All dreams, whether pleasant or unpleasant, interfere with your rest, and if you do need the rest and do wish to wake up refreshed in the morning, then it is best to stop dreaming.

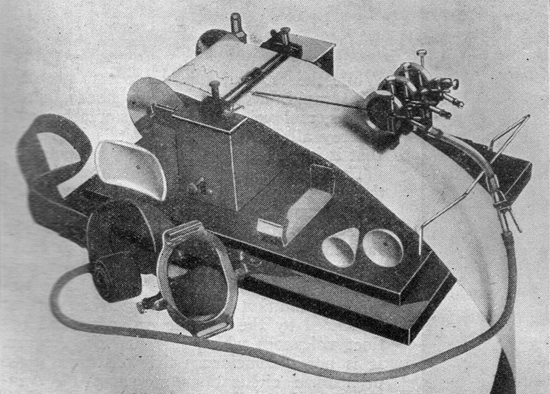

Recordings of a dream taken from a polygraph in 1926.

Gernsback’s research, an early attempt at simply recognizing dreams based on changes in heartbeat, was also published in that 1926 issue.

In case “A” it will be observed that the apex beat increases almost instantly to four times the normal sleeping rate. In “B” and “C” on our graph it becomes difficult to actually note the apex beat because of the influence which breathing has upon the heart record.

The gradual undulations of the curves in the normal record are produced by the process of inhaling and exhaling. The inspiration in all of the cases is much greater under the excited reaction of a dream than in the normal sleeping state. Notice also that the respiration is changed when the subject changes his or her position during sleep, and you will also see that when dreaming, in case “C” the heart rate was stimulated immediately after the change of position.

In “C” an electric bell was used to awaken the subject, being rung softly at first and then permitting the bell to remain quiet until the subject again assumed normal respiration and heart curves, and then the tone was increased until the subject eventually awoke. Although a slight disturbance took place every time, it was not as marked as just before awakening, at which time this patient recalled a dream of an alarm clock awakening her and summoning her to work.

It is obvious from records which have been obtained that dreams do affect not only respiration but also the heart beat, and that the dreams of some subjects stimulate the heart to a greater extent than those of another. It is believed that this is the first attempt made to record heart action during sleep, laying particular stress on the heart action of subjects who dream a lot. The experiments have not yet developed to a point where a record was taken during a nightmare or one taken of an individual who frequently walks in his sleep.

Polygraph machine from 1926.

Personally, I don’t dream much. But when I do, for whatever reason, they’re generally pretty dark and unsatisfying. (Perhaps I should try Gernsback’s method of not eating anything for hours before bedtime.)

Unlike Gernsback, though, my own anecdotal experience with dreams and the quality of my sleep is the inverse of his. I’ve recently experimented with melatonin, which has aided in my ability to sleep for longer stretches during the night. But I’ve noticed a marked increase in dreams—which as I’ve mentioned are not the most pleasant.

So maybe I won’t be taking up 21st-century researchers on their dream recorder anytime soon.