A pick-up had crashed into the airport sign when I arrived at Gerald R. Ford International Airport in Grand Rapids. Snow was falling, and cars eased gently by. I snapped a photo for Facebook.

“Welcome back! It’s the same old Michigan you left,” a high school friend commented. But it’s not. Since I moved away more than two decades ago, Michigan’s political landscape has changed dramatically. Once a moderate state of strong unions, good public schools, and live-and-let-live values, Michigan in the last two decades has been turned into a laboratory for ideas from the far right: privatizing education, slashing taxes on businesses, and limiting collective bargaining. What the hell happened? How did the centrist state of my youth go the way of its forests, clear-cut for cornfields?

I opened my investigation very unscientifically by interviewing my favorite cousin, Dave. I think of Dave as a pretty typical Michigander. He lives with his family in Allegan County, where we both grew up, a patchwork of farms and small towns strung along section-line roads. It’s one of the redder parts of Michigan, and Dave, who has served on the Trowbridge Township board, describes himself as “probably a Republican.” His wife, Judith, a graphic designer who grew up in Mexico, is probably not. (In Michigan, 12.8 percent of households are “mixed party,” about double the national average.) Over dinner at their house, Judith told me she feels upset by what she perceives as an uptick in racism since the election of President Donald Trump. Dave and Judith were both proud when their son, a college student, went to the women’s march in Lansing with a Latinx-heritage group. They are moderates, a breed common in the state but increasingly rare in the statehouse.

Consider guns. Like many rural and small-town Michiganders, Dave hunts and owns guns. Asked how many guns, he gave the same answer he gives Judith about ex-girlfriends: “More than one, less than a hundred.” He has paid dues to the National Rifle Association, but he also thinks gun safety laws could be strengthened. He doesn’t think gun-free zones work, but he supports higher minimum ages, better training, and banning machine guns. This is probably in line with the Michigan electorate. A Gallup poll in October of 2017 found that 71 percent of Midwesterners believe in gun registries, 73 percent support 30-day waiting periods, and a whopping 94 percent support universal background checks. None of these measures has even been proposed by Michigan’s legislature, however. Instead, the state legislature recently passed bills allowing concealed carry with a license in no-carry zones and penalizing cities and towns that pass gun laws more restrictive than the state’s.

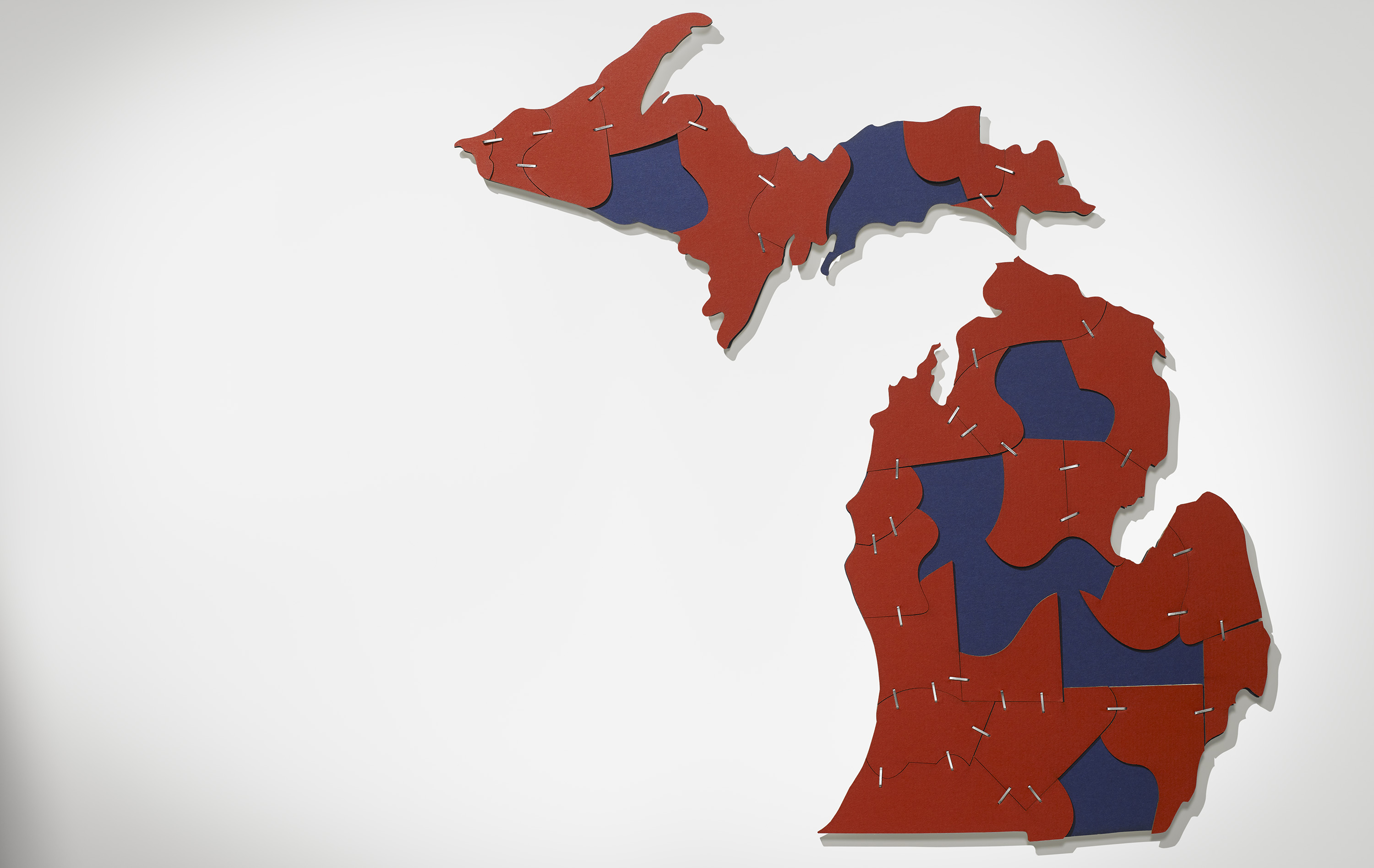

Gun-safety legislation is just one example of how the statehouse is grossly out of step with what Michiganders want. Trump squeaked by to win Michigan by fewer than 11,000 votes, and the state hadn’t voted for a Republican presidential candidate since George H.W. Bush. Michigan routinely elects moderate governors. Yet the congressional delegation from Michigan is nearly two-thirds Republican, and the statehouse in this solidly moderate state has, since 2011, been controlled not just by Republicans, but by the party’s far right.

How is this possible?

It begins with manipulating maps to rig elections.

Once a decade, during every year that ends in zero, there’s a national census, followed by a constitutionally mandated round of reapportionment to determine how many representatives each state will send to Congress. Congressional districts and state legislative districts must then be redrawn to reflect changes in population. In 34 states, the new congressional maps are generated by the state legislature or by commissions under legislative control. Not surprisingly, legislators often make politically motivated district maps, or gerrymanders. Sometimes incumbents from both parties cooperate to protect their seats. Other times the party in power draws maps to lock down majorities and to disadvantage the opposition. The latter, dubbed partisan gerrymanders, have faced legal challenges, most prominently Gill v. Whitford, which the Supreme Court punted on in June, remanding the case to its Wisconsin district court. The justices declared that the plaintiffs lacked federal standing, because they had not proven “concrete and particularized” injury to themselves as individuals, but had instead argued injury to Democrats statewide. But in a concurring opinion joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor, Justice Elena Kagan predicted a rematch, noting that gerrymandering was a threat to democracy because “it enables a party that happens to be in power at the right time to entrench itself for a decade or more, no matter what the voters would prefer.”

Case in point: Michigan. The state legislature is in charge of redistricting, per the state constitution. That legislature happened to be controlled by Republicans in 2001 and 2011, years when the governor was Republican as well. And now Michigan has some of the most partisan maps in the nation. They were not drawn that way by chance. In 2010, REDMAP—the Republican State Leadership Committee’s Redistricting Majority Project—spent $1 million on Michigan state legislative races, with the express purpose of influencing the redistricting process. “The effectiveness of REDMAP is perhaps most clear in the state of Michigan,” the committee’s 2012 report declares. In November that year, Michiganders cast nearly 53 percent of their votes for Democratic congressional candidates and about 47 percent for Republican candidates. Nevertheless, the report bragged, “voters elected a 9–5 Republican majority to represent them in Congress.”

How can voters “elect” a legislature so unrepresentative of the electorate? The Republicans in charge of drawing the maps shifted the borders of districts to put just enough Republican voters into a large number of districts in order to win them safely, and put many more Democrats into districts that were already overwhelmingly Democratic in order to limit the influence of their votes. Experts call these tactics “cracking” (spread out voters to give yourself a small but safe advantage in many districts) and “packing” (pack your opponents into as few districts as possible). In 2016, Michigan Republican House members won their districts by a 21.6 percent margin of victory on average. Michigan’s winning Democrats averaged margins of 40.6 percent. Winning districts by large margins is inefficient—just as losing by small margins is inefficient. It “wastes” a lot of votes by not translating them into seats. Social scientists call the difference in the percentage of votes each side wastes an “efficiency gap”—a metric that can be used to quantify partisan gerrymandering.

Setting aside the jargon, gerrymandering means legislators draw maps that make their own party’s votes count more than the opposition’s. And then the fun really begins.

Ratfucking 101

Battle Creek is known as Cereal City, U.S.A. When my mother grew up there it was a thriving city of unionized workers at Post and Kellogg’s. Today it has the usual Rust Belt woes: scarce good jobs, a hard-hit economy, a blighted downtown. The city is in Calhoun County, which used to be part of Michigan’s 7th congressional district. The 7th included counties to the east and south—similar places composed of agricultural land interspersed with small cities still reeling from the recession. It was a swing district. But the redistricting of 2011 excised Calhoun County from the 7th and appended it to the safely conservative 3rd district. According to Michigan political rainmaker Bob LaBrant, this was done for one reason: to block Mark Schauer. A Democrat, Schauer had won the district from its Republican incumbent in 2008, then narrowly lost it in 2010. Republicans wanted to deny Schauer the chance to win again. “To solve that you just take Calhoun out of that district and put it in the 3rd district, which was, at the time, the second most Republican district,” LaBrant told writer David Daley.

(Map: Michigan Department of Technology, Management and Budget)

When I tracked down Mark Schauer in Kalamazoo, where he now works as a political consultant, he cited that quote.

“Did you read Ratfucked?” he asks, lowering his voice, as most Michiganders do when mentioning Daley’s book.

“They essentially dared me to run in the new 7th district,” Schauer says. He chose not to. But he had no real connection to most of the communities in the 3rd, so he chose not to run there either. The redrawn 7th is more solidly Republican now.

Meanwhile, as part of the safely conservative 3rd, Battle Creek citizens vote Democratic to no avail, and their congressional representative, Republican Justin Amash, who lost the city but won the seat in 2016, has little need to care about them.

“You never feel like anybody’s listening to you anymore,” declares Sharon Heisler, describing a town hall with Amash. Heisler is my godmother Gail’s friend. I visited them in Battle Creek, where my mother and Gail grew up together. At the town hall, Heisler says, several people raised concerns about Amash’s yes vote for House Joint Resolution 40, a bill ensuring that people who qualify for disability because of a mental disorder don’t need extra screening to buy guns.

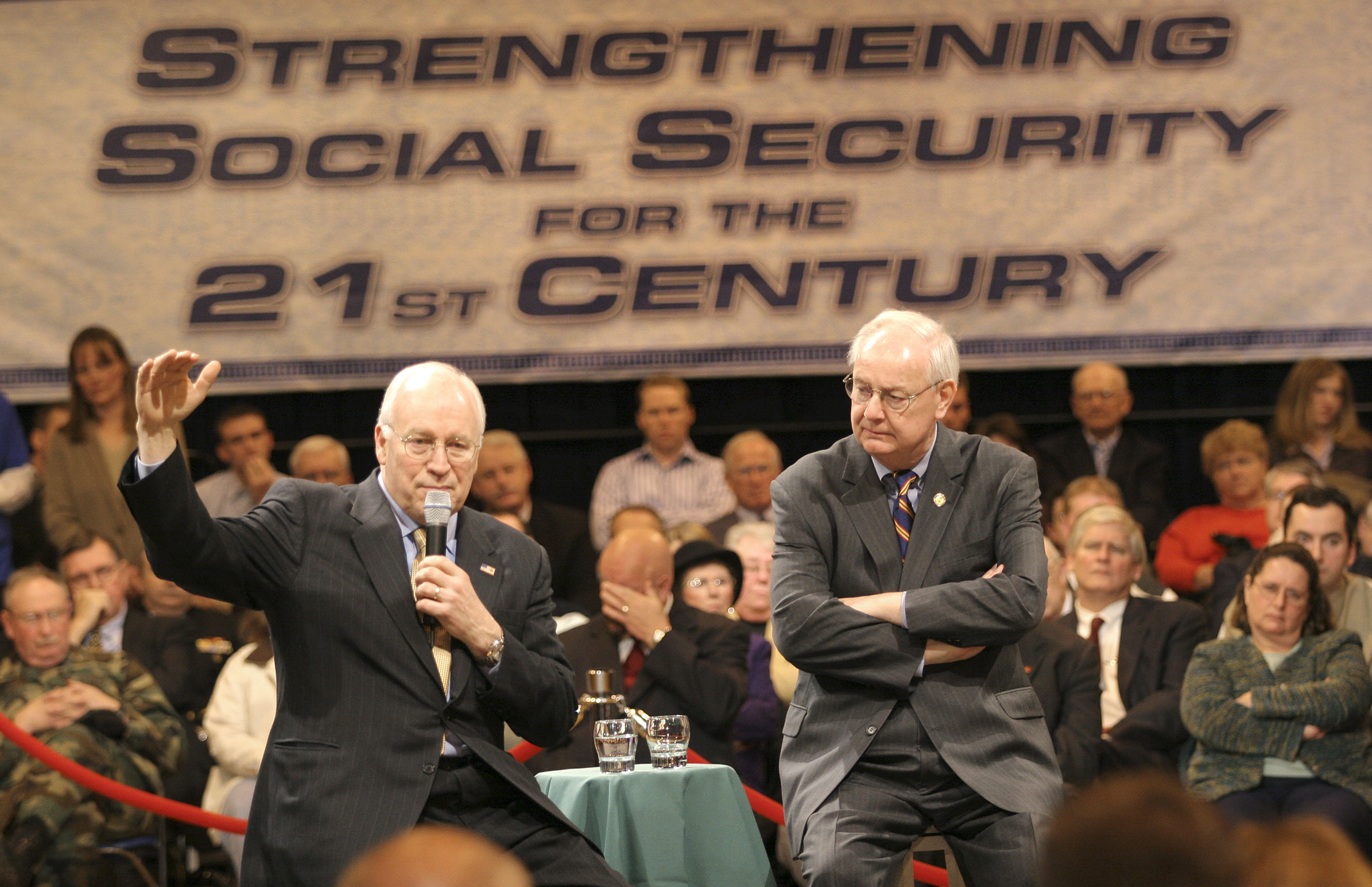

(Photo: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images)

“There were several people in there who brought that up, and he just really basically refused to answer,” she says. “There was just no argument—I didn’t mean to say argument—there was just no representation of, well, there could be two sides.” Heisler, who says she has voted for both parties, comes from a family of hunters and gun owners, but like 92 percent of American voters who responded to a 2018 Gallup poll, she believes in universal background checks.

“The fundamental impact of gerrymandering is that the elected officials are no longer accountable to the majority of their voters,” says Kelly Ward, executive director of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee. “The vast majority of people in the states and in Congress want their members to pass rational gun reform,” she says. “Gerrymandering creates the situation where you can’t get that done.”

Hi, How Are You? Go to Hell.

The problem goes beyond legislators not representing the wishes of the electorate. As Joe Schwarz explained, gerrymandering pushes everyone to hyper-partisanship. Schwarz represented the 7th district as a Republican in Congress back when it was a swing district. Before that, he was a state senator.

“I served in the [state] senate when there was great communication,” he says over breakfast at a packed Pancake House in downtown Battle Creek. “People’s first loyalty was where it should be, to the state of Michigan.”

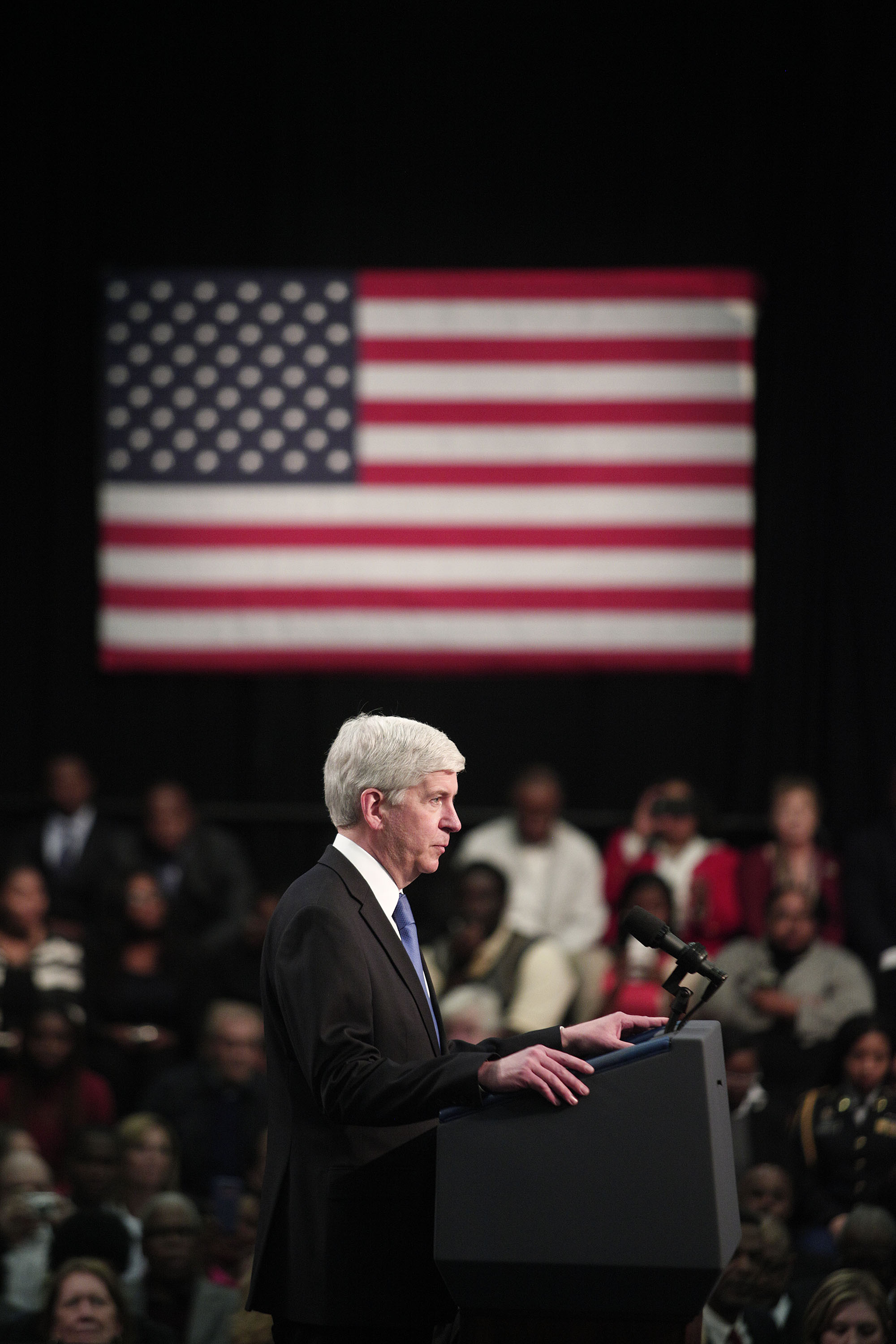

(Photo: Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

Schwarz dates the change to 2010, when Republicans rode a red wave to control all three branches of state government. Not only did they redraw the maps in 2011—and since then all three branches of government have remained in their hands—but afterward, secure in their majorities, they embarked on an ambitious program of ultra-conservative lawmaking, passing limitations on collective bargaining, reducing the amount of time the out-of-work can draw unemployment, and repealing the Michigan business tax. By the end of 2011, the new governor, Rick Snyder, had signed 323 bills into law. Three hundred and seven of them were sponsored by Republicans—in a state where citizens divide roughly evenly along party lines.

Snyder, an accountant and venture capitalist who campaigned as a moderate with the moniker “one tough nerd,” claimed that right-to-work legislation, a perennial conservative wish-list item, was not on his agenda. And yet, in December of 2012, with thousands of protesters chanting outside, the state capitol doors were barred as the legislature passed a “right-to-work” law limiting the power of unions. Michigan was then seventh among states for rate of union membership; polls after the right-to-work bill passed showed only 41 percent of the population supported it. Mark Schauer was among the protesters who were pepper-sprayed in Lansing. “The quick, party-line vote in the legislation in December of 2012 shouldn’t be interpreted as public support,” he says. Yet, in a move perceived by many as caving to the far right, the governor signed the bill.

This is not representation: It’s ideological warfare. The gerrymanderers have weaponized the legislature.

“What you want are good electoral contests in November,” Schwarz says. “You don’t want the election to be decided in the primary.” And yet, in a gerrymandered state, that’s exactly what happens, because so many districts are drawn to be safe. And when races are won in the primary, elected officials don’t fear the opposition; they fear being outflanked from their own side. They feel accountable not to those they represent, but to the most extreme ideologues of their own party—or to organizations, like the NRA, that will fund a primary challenger if elected officials don’t toe the line. Politicians even have a word for this: Don’t disobey, they say, or you’ll be “primaried.”

“It serves no useful purpose in a state like Michigan if you have a legislature that’s so dominated by one party they don’t really have to communicate with the other party, who represent half the people, at least,” Schwarz says. “You know, in the state senate now the Republicans just do this to the Democrats: ‘Hi, how are you this morning? Go to hell.’ The caliber of expertise and ability to understand what a legislature should be and what a legislature should do is not what it used to be, in many ways because of gerrymandering.”

Packing

Gerrymanderers like to blame geography, not intent, for the Republican stranglehold on state decision-making. Democrats, they say, pack themselves into dense urban areas, while Republicans spread out in rural counties. And someone has to draw the lines somewhere, says Allegan County Clerk Bob Genetski. A former English teacher, Genetski used to represent the 88th district in the State House, where his chatty, ebullient brand of wonky conservativism must have served him well. “Let’s go look at the map,” he says as soon as I start asking questions. I found the invitation charming.

Genetski was in the State House when the last round of maps passed, and I asked him to explain why Republicans added Calhoun County to the 3rd district, when that meant they had to take some voters from Kent County, the heart of the district, out. (Michigan guidelines say districts should break as few county lines as “reasonably possible.”) The voters they chose to jettison were in the rapidly diversifying southern suburbs of metro Grand Rapids: Those working-class voters were tossed into ultra-conservative 2 district.

(Photo: Scott Legato/Getty Images for MoveOn.org)

“Congressional districts … I know they do have to be drawn to exact number,” Genetski declares, evading the fact that people were moved out to offset the ones moved in. “They’re also bound by the 1965 Voting Rights Act,” he says when pressed, “which says that they have to draw at least two—and it might be exactly two—majority African-American districts in Michigan every time reapportionment is done.”

I liked Genetski, so this was shocking, if not blatantly misleading, since how districts are drawn in Detroit—the African-American districts he referenced—has absolutely no effect on how they’re drawn in Grand Rapids. Furthermore, it recycled a common misrepresentation of the Voting Rights Act.

“Under no circumstances does the Voting Rights Act require packing,” says Michael Li, an election law and redistricting specialist at the Brennan Center for Justice. “It’s not about numbers; it’s about effective minority power.” The Voting Rights Act does not mandate a percentage of minority voters; it simply requires that states do not draw districts that purposefully disenfranchise minorities. In fact, more than half of the United States’ 122 majority-minority districts do not have a majority of any one ethnicity. But the Voting Rights Act is frequently used as an excuse to create heavily majority-minority districts that actually dilute the minority vote, as with Congressional districts 13 and 14 in Detroit, which, Genetski says, “have roughly 53 to 55 percent African Americans in them.” In fact, district 13 is 56.6 percent African American and district 14 is 58.3 percent. This matters too.

“Making a district 2 percent more African American doesn’t seem like a lot,” Li explains, “but what it does is it makes the other surrounding districts like 53 percent Republican instead of more 50-50 Democrat-Republican. It was clearly a strategic tool.”

The 2011 maps worked spectacularly well. In the first state elections after redistricting, 89 of the 110 races were won by more than 10 percent—35 of them by more than two-to-one. There were just eight competitive races—those won by 5 percent or less—for the Michigan House of Representatives. In 102 out of 110 districts, the race was essentially won in the primary.

Swings and Schools

Muskegon, a former lumber port on the shore of Lake Michigan, is a small but attractive industrial city with a diverse population and fairly high poverty. Along with a few surrounding townships, the city makes up the 92nd, a Democratic State House seat. The 91st district, one of the state’s eight swing districts, encircles Muskegon like a backward C, comprising many of the city’s outlying areas, from gorgeous lakefront homes to small towns to hardscrabble, backwoods townships. It was here that the closest State House race in 2012 was won, by less than 1 percentage point.

Collene Lamonte was a math and science teacher in the Muskegon Public Schools when she heard on the radio in 2011 that the newly elected Snyder had introduced a budget cutting millions of dollars from education funding.

“I was just like, ‘This is a trainwreck,'” she says. “If you’re rich, you’re going to be able to send your kids to the nice private school, but the rest of us are going to be left without anything.” She realized she could “sit in the teacher’s lounge and bitch,” or she could do something. So she ran for the State House. In November of 2012, she took the seat from the Republican incumbent, Holly Hughes, by 333 votes. She headed for Lansing in early 2013, hoping to change the path the state was taking on education.

(Map: Michigan Department of Technology, Management and Budget)

Education is the arena in which Michigan has been conducting perhaps its most dramatic experiment in privatizing government functions. Conservative forces in the state, most prominently Republican power couple Dick and Betsy DeVos, have long advocated moving funds from public schools into voucher systems that can be used to pay for private or parochial schools. Michigan voters rejected this in 2000. But the state has long committed itself to school choice: Since 1996, parents have been allowed to opt their children out of schools they don’t like and enroll them in other ones. The state pays out a per-child amount that follows the child—whether they enroll in another public school or in a charter school.

A key idea behind school choice is “let the market decide.” Schools that are succeeding will gain more students; schools that are not will have to close. But Lamonte worries about the kids whose parents didn’t know to move them, or couldn’t transport them to better schools: Those kids get left behind in schools with ever-dwindling resources. “That’s the thing with schools of choice. It literally undermines and disrupts all of the financial stability within a school district,” Lamonte says. “As more students leave, dollars leave, and you literally don’t have the critical mass left to support the programs you had in place for years.”

The African-American community of Muskegon Heights had once enrolled more than 2,000 students in its school district, but after losing more than a quarter of them to school choice, the district had been forced to cut programs and close schools. The insolvent district finally requested help from the state, and, in 2012, the governor appointed an emergency manager who fired all the staff, sold unused school buildings, and auctioned off “excess” property—including one elementary school’s playground equipment. “They saw their playground equipment going off in a big, flatbed truck,” says Mary Valentine, another former representative from the 91. “Anything of value was taken and sold for pennies on the dollar.” The emergency manager gave Atlanta-based for-profit charter company Mosaica Education a five-year contract to manage the district. It was the first time in the state that an entire school district was privatized.

Michigan legislators have heartily embraced charter schools, even as both school choice advocates and critics have raised concerns. As early as 1999, a report issued by Michigan State University scholars friendly to school choice questioned the lack of accountability among charter schools and raised concerns about students left behind in defunded schools—particularly in low-income and minority districts. Yet the number of charters in the state has steadily increased: Nearly 10 percent of all Michigan students are now enrolled in them. At the same time, educational outcomes in the state have worsened. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, in 2000, Michigan’s fourth graders were 10 in the nation in math. In 2017, they were 39. Reading scores have also suffered a steep decline. And yet the DeVos family has continued to push for more charters and less oversight of them through the PAC they founded, the Great Lakes Education Project.

Currently, the state sends a billion tax dollars a year to charter schools—61 percent of them operated by for-profit companies. (Nationally, 16 percent of charters are for-profit.) According to the New York Times, a 2015 federal review noted that an “unreasonably high” number of charters were among the state’s worst performing schools. One year earlier, a bill had gone into effect, passed in those heady, early days of 2011, removing the remaining limits on the number of charters that could open in a district. The only charters that are limited in Michigan now are cyber schools.

“As soon as the Republicans took control of everything in Lansing, they immediately started pushing through these bills,” Lamonte says. “It was like they had them just sitting there waiting.”

Lamonte got herself appointed to the House committee for education. But she quickly realized that, as a minority legislator from a competitive district, she was going to be kept in check by the party in power. “Anything that had my name on it basically was going to die in committee,” she says. Republicans, determined to win the district back, would not want to let her rack up legislative accomplishments to run on.

In 2014, Holly Hughes took back the 91 district by 53 votes. It was the most expensive race in the state that year. One of Hughes’ top campaign contributors was the DeVos family. That same year, Mosaica bailed only two years into its five-year management contract for the Muskegon Heights school district. “It didn’t fit their financial model,” the district’s emergency manager told the Muskegon Chronicle. “The profit just simply wasn’t there.” The district has been struggling to get back on its feet ever since.

The Midas Touch

Buried in that raft of conservative legislation passed in early 2011 was a bill creating a special fund for purchasing what senate Republicans called “state-of-the-art anti-fraud software” for the state’s Unemployment Insurance Agency. The $44 million Michigan Integrated Data Automated System, or MiDAS, was put in place in record time, and the UIA subsequently laid off more than 400 employees. Sometime around October of 2013, MiDAS began scanning unemployment claims from the previous six years for inconsistencies. When it found a discrepancy between what an employer and an employee reported, it assumed the employee was guilty, and automatically issued a fraud determination. In most cases, there was no human oversight.

(Photo: Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

As a result, Lamonte spent much of her two years in office helping constituents defend themselves in what came to be known as the unemployment insurance fraud scandal. “Literally almost every single day we had UIA complaints that came in,” she says. “People that had applied for unemployment, they were due the unemployment, but the system had kicked them back out and said they weren’t eligible.” Often they were ordered to pay enormous fines. “It wasn’t just that they had to pay the money back. They had to pay four times the money back,” Lamonte says. “They literally were bankrupted; it was awful.”

“The most evil part of the whole thing is it is programmed to collect on you immediately,” says Tony Paris. “It can take your state and federal tax returns and garnish up to 25 percent of your wages.” The lead attorney at Sugar Law, a non-profit, public-interest law center, Paris has handled hundreds of MiDAS-related cases. When I contacted him to learn about the debacle, he suggested I accompany him to Lansing for a hearing. As we roared toward the capital, Paris weaving his Ford Focus in and out of traffic and slamming cough drops, he told me about his “insane barrage” of clients. Many had collected unemployment years earlier, and only found out that they were accused of fraud when they received a bill in the mail. Others learned of it when their tax refunds were taken or their wages garnished. Some never received the bills because they had moved. Many received no explanation of their alleged fraud, and the system kept piling on interest. People lost their homes, went bankrupt, lost custody of their kids, he said. “I had a woman write the judge a letter saying she thinks about killing herself.”

Legislators were slow to address citizens’ complaints. Lawyers spent 2014 trying to sort through the barrage of cases. Administrative judges, who are tasked with ruling on contested cases, were overwhelmed. Paris deposed so many clients he got vocal nodes. In 2015, Sugar Law and the United Auto Workers joined with some of the accused to sue the state. A settlement was reached whereby the state agreed to start allowing reviews of fraud cases. That year, the legislature roused itself, passing laws to reduce the statute of limitations on unemployment fraud, to require human oversight of the system, and to reduce penalties. As of 2017, the state had reversed nearly 48,000 fraud determinations—which included about 85 percent of the accusations MiDAS issued without human oversight or review.

Paris’ client, Keely Pearce, had borrowed a friend’s car in order to drive from her home in Grand Rapids to the administrative hearing office in Lansing, where we met her in the waiting room. With her whitish-blond hair in a turquoise scrunchie, she looked like somebody’s grandmother.

“I don’t believe I did anything wrong. That’s what’s so frustrating about this,” she told me. We proceeded into the small room where an administrative law judge questioned Paris and the lawyer for the UIA for over an hour. Pearce testified that she did not receive any information about the charges or her rights of appeal. The state had no proof of service. The record showed that many of the bills weren’t even sent to her correct address. Even now, she didn’t understand what she had been accused of. On Paris’ advice, she testified that she had dropped out of high school as a pregnant teen. After an hour and a half, the judge overturned the fraud charge. Pearce seemed unsure of what had happened until we were back in the waiting room and Paris explained that she had won—for the moment, since the UIA could still appeal.

This seemed over-cautious at the time. It wasn’t. The state appealed Pearce’s case, and, in August, the Michigan Compensation Appellate Commission ruled 3–0 in Pearce’s favor. The UIA has now appealed to the Circuit Court of Kent County.

Paris’ response: “Why is the state doing this to their own citizens? Why?”

Detroit vs. Everybody

“These are not your father’s Republicans,” Paris had told me on the way to Lansing. “These are full-blown, what-can-we-do-to-strangle-and-destroy-the-support-system Republicans.”

It’s hard not to feel that way when considering what has happened to Detroit. The city’s story is practically synonymous with Rust Belt decline: Once a metropolis of 1.8 million, its population is now barely 700,000. But the citizens who remain are lively, and they are not giving up. “Detroit vs. Everybody,” reads a popular T-shirt.

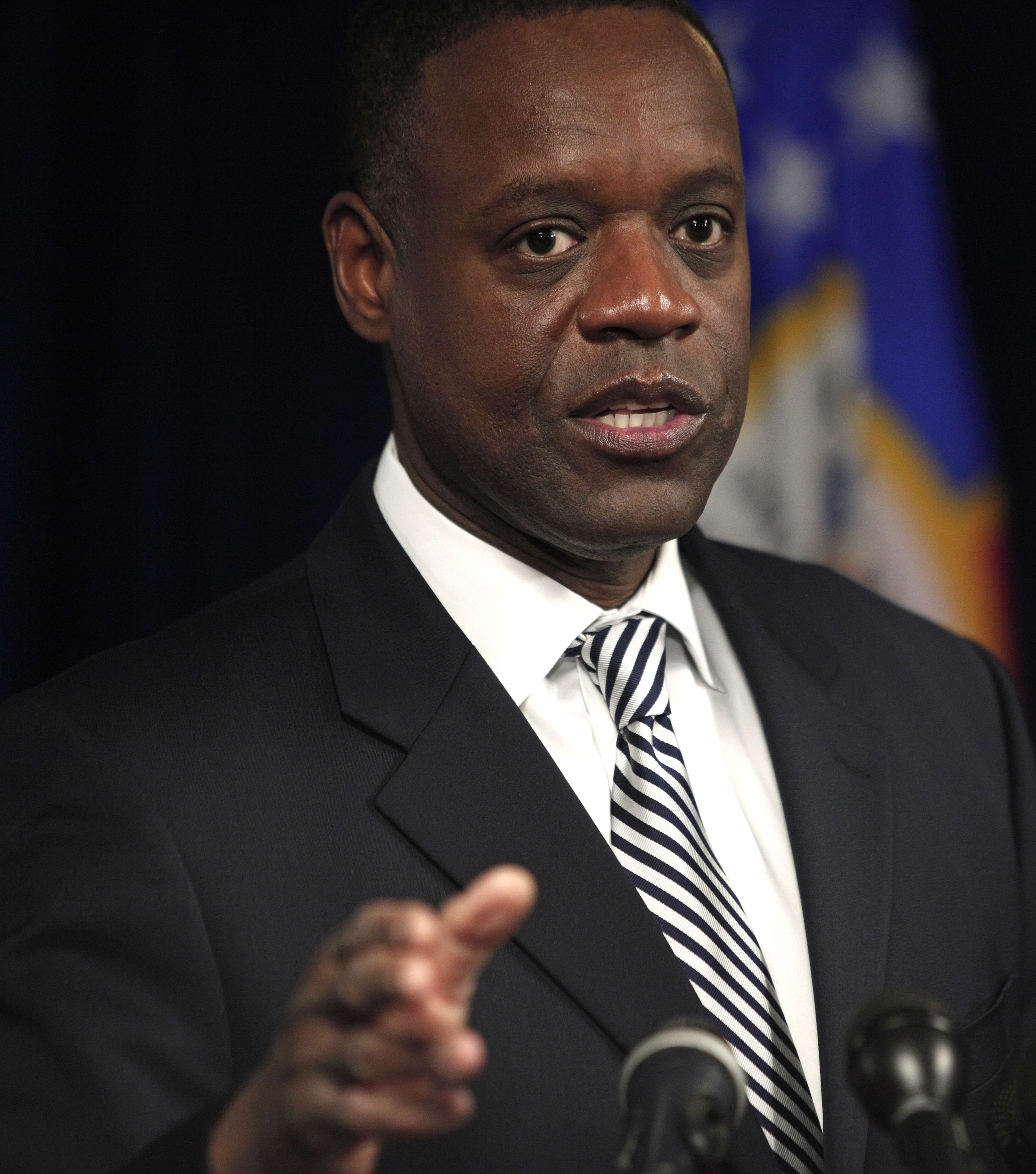

(Photo: Mark Wilson/Getty Images)

Some of the most dramatic changes to the legislative maps in the 2011 redistricting process happened in the Detroit metropolitan area. Because Michigan’s population grew more slowly than the nation’s, legislators needed to eliminate one congressional seat, and so the redistricting committee decided to axe the 9 district, represented by Democrat Gary Peters. In the process of doing so, they redrew all the Detroit-area districts. The weirdest was the new S-shaped 14th district, which reached an arm out from Democratic, downtown Detroit to grab the diverse city of Pontiac, packing those two cities’ liberal, minority voters into one district so their votes would count even less. In an email exchange about the new maps, a Republican congressional aide declared, “In a glorious way that makes it easier to cram ALL of the Dem garbage in Wayne, Washtenaw, Oakland and Macomb counties into only four districts.” Presumably it was also glorious to pit Peters—now in the new 14th—against first-term Democrat Hansen Clarke, then one of only two representatives of color from Michigan. The two sitting Democrats were put in the position of running against each other in 2012; Peters won. Meanwhile, the well-heeled, white suburbs of Bloomfield Hills, Birmingham, and Farmington were excised from the 14th and used to shore up the Republican 11th district next door.

Despite having reduced the influence of “Dem garbage”—or, rather, Detroit—in Congress, Republicans argue that the city has done well on their watch. When Detroit got itself into a financial mess, they say, Snyder and the legislature bailed it out. Whether you buy this story depends largely on your feeling about emergency managers.

Nineteen states and Washington, D.C., have laws allowing the state to assign emergency financial managers to work with elected officials to aid insolvent municipalities. Michigan’s law was put on steroids in the exuberant lawmaking days of early 2011. Emergency financial managers were suddenly empowered to act “for and on behalf of” elected officials. They could issue binding orders to elected officials, fire administrators, privatize municipal services, sell public assets, and break collective bargaining agreements—all without regard for the wishes of a community that hadn’t elected them.

The law was so unpopular that a referendum rescinding it got on the ballot, and, in 2012, all but seven of Michigan’s 83 counties voted to repeal it. A month after the law was revoked by popular vote, the legislature lawmakers attached an appropriation making it immune to reversal by referendum. In essence, they offered a middle finger to the electorate.

The situation is all the more unjust because emergency manager legislation disproportionately affects Michigan’s black citizens. When voters rejected the emergency manager law, four cities—Pontiac, Flint, Benton Harbor, and Ecorse—were under emergency managers. Three of them were majority African American, and the fourth, Ecorse, nearly was. When Detroit was added to that list in March of 2013, roughly half the state’s black citizens had their elected municipal government superceded by state-appointed officials.

“The kind of power that was pretty much taken from the citizens of Detroit and given to this one man, the emergency manager, it was just unbelievable,” says Linda Campbell, a well-known equity activist. “And the fact that Detroiters and Michiganders had voted against the emergency manager law, only to have the state come back and impose it again, was just shocking to a lot of us.”

(Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Soon after the new legislation took effect in 2013, an emergency manager for the city of Flint decided to save money by disconnecting the city from Detroit’s public water supply. In April, Flint residents began receiving water from the Flint River. Throughout 2014—the same year lawyers were scrambling to figure out what was going on with unemployment insurance—Flint citizens were complaining about the smell and color of their water. Reports of high lead levels began in February of 2015 and continued through the year, but officials scoffed. Flint city council members voted seven to one in March to disconnect from the Flint River, but the emergency manager overruled them. It was October of 2015 when Snyder finally announced that Flint would be reconnected to Detroit water. The tragedy of the water crisis in Flint might have been addressed much sooner if state legislators were in the habit of listening to their constituents.

Detroiters, meanwhile, had their own elected city council disempowered, its decision-making powers handed over to Kevyn Orr, a lawyer from the firm Jones Day. Shortly after Orr took the helm, Jones Day was hired to take Detroit through the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history. Pensions were cut. Public assets, such as city vehicles, were sold off. Joe Louis Arena was demolished, the land it was on given to a creditor for development. Garbage service was privatized.

“They restructured local government,” Campbell says. “They restructured some of the city departments—like the water department is no longer under the control of the city of Detroit. It’s now a [regional] authority. They created a land bank authority and public lighting authority and a regional transit authority. These are public-private structures where there’s little if any true accountability to the citizens, because they have their own governing structure.”

(Photo: Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

Under emergency management in 2014, the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department began aggressively shutting off the water in homes whose accounts were more than $150 delinquent. Since 2014, more than 90,000 homes and buildings in Detroit have had their water shut off. Two independent experts sent by the United Nations warned that shutting off water to people who can’t pay is “contrary to human rights.” Yet while I was in Detroit, the water department announced that water shutoffs, which had been on hiatus for the winter, were about to resume, and that 17,000 households were expected to be affected.

The city exited bankruptcy at the end of 2014, thanks in large part to a funding drive by the Detroit Institute of Arts, which raised $800 million in order to avoid being forced to sell off art from its collection. Detroit Public Schools remained under emergency management from 2009 to 2014, during which time the district’s net deficit more than quadrupled. Meanwhile, dozens of new charters opened in the district, even as the number of students steadily dropped. With little oversight and almost no regulation of where schools can open, some neighborhoods ended up with a multitude of options; others have almost none. Some schools are excellent; others are abysmal. There are few resources to help parents figure out the system and determine where to send their kids.

By late 2015, Detroit public schools were in financial crisis. The Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren, a bipartisan group of civic, business, religious, and educational leaders, urged the state to assume the district’s debt and return their schools to the elected school board. They also recommended establishing an education commission to ensure greater transparency and coordination between the public schools and the charters. Charter school advocates fought back. Betsy DeVos wrote an opinion piece for the Detroit News arguing that, rather than provide more oversight of charters, legislators should eliminate the entire public school district.

The coalition took busloads of parents, teachers, administrators, and students to Lansing to testify. But the pro-charter groups had been to Lansing too. The DeVos family alone had dropped more than $110,000 on seven GOP members of the House Appropriations Committee. The House bill included a plan to return power to the Detroit school board, but the education commission was left out. Betsy DeVos was named secretary of education the following year.

Detroiters still have no voice in whether and where charter schools can open in their city. In 2018, on Michigan’s annual list of failing districts and schools, 16 of the 21 were charters. Seven of the charters were in Detroit.

Today, Snyder touts Detroit as a “comeback city.” The population has stabilized, and the downtown core is spiky with gleaming office towers and an expensive new sports arena, thanks to generous tax abatements handed out by the state. There’s a rapidly gentrifying corridor along the historically elegant Woodward and Cass Avenues, where the hulking new Carhartt store exudes hardscrabble hip. But beyond that 7.2-square-mile downtown, there’s over 130 square miles of neighborhoods that still struggle to get basic policing, power, and water. Activists like Linda Campbell point out that this style of development is “resegregating” the city. Attempts to ensure that tax giveaways include community benefit agreements guaranteeing racial equity have met with resistance. “Long-time Detroiters are struggling to have a voice in what’s happening,” Campbell says.

The great irony of Detroit’s bankruptcy is that the city’s financial crisis was precipitated in part by the state. Since 1994, Michigan’s legislature has diverted more than $5.5 billion in state sales tax away from cities and toward the state bureaucracy, according to an analysis by Great Lakes Economic Consulting, a non-partisan firm. In the Great Recession, as property-tax and income-tax revenues plummeted, these cuts to revenue-sharing continued. This is not normal state behavior. According to GLEC, from 2002 to 2012, 45 states increased revenue-sharing for municipalities by an average of 48.1 percent. Four states reduced revenue-sharing by around 10 percent or less. Michigan was the outlier, slashing state revenue-sharing by 56.9 percent. In essence, the state strangled its cities. Detroit’s emergency manager himself noted in his initial report that Detroit’s funds from the state decreased from a peak of $334 million in 2002 to barely half that, $173 million, in 2012. The bankruptcy was avoidable, but it did accomplish one thing: the neoliberal dismantling of one of America’s great majority-minority cities.

Whither Democracy?

In 2016, the Center for Michigan conducted a statewide survey of residents. The majority had “low” or “very low” trust in their state government. Ninety percent thought it was “crucial” or “important” to fix state oversight of public education. Even more felt that way about the state’s ability to protect the environment, protect public health, and foster economic growth.

“Elected representatives should be representing the people,” one participant declared. “They are public servants. We do not see that in the state.”

Gerrymanderers like to point out that gerrymandering has been going on since the nation’s beginning—it can’t be a threat to democracy. But the founding fathers could never have foreseen the vast amounts of incredibly predictive data the digital world would provide to mapmakers, nor the sophisticated technology that would allow them—both Democrats and Republicans—to leverage that data to hinder the opposition. Today, gerrymanderers can use “augmented voter files” to predict individual voter behavior with high precision and powerful mapmaking software to generate thousands of maps with differing district borders, predicting with high certainty how each map will perform. Increased computing power will likely be used to make ever more biased maps that will appear to comply with redistricting principles—even as they entrench political biases and erode our political system further.

(Photo: Jeff Kowalsky/AFP/Getty Images)

Thirty-eight states have introduced legislation to regulate or reform redistricting, by taking it out of the hands of politicians, requiring citizen oversight, prohibiting map-drawing with the intent of disfavoring one party, or banning the use of political data in creating new districts. Michigan is one of five states where citizen-led ballot initiatives are being considered in 2018. Voters Not Politicians, a non-partisan group, has a constitutional amendment on the Michigan ballot that would take the job of redistricting away from politicians and give it to a citizens’ commission, similar to those that exist in Alaska, Washington, California, Idaho, Montana, and Arizona. The group started as a Facebook post and evolved into an army of volunteers who collected more than 425,000 signatures, coming from every county in the state.

Bruce Denniston, whom I hadn’t seen since high school, was one of the signatories. On one of my last nights in Michigan, I met up with Denniston in Grand Rapids. We used to call it Bland Rapids, but lately the city is changing. Huge influxes of private money have helped make it one of the fastest-growing city economies in the Midwest. Its downtown is practically a monument to Amway, the multilevel marketing empire owned by the Van Andel and DeVos families. There’s the huge DeVos Place convention center, the DeVos Performance Hall, the Van Andel Arena, the Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel, and, in a rare bit of anti-Amway cheek, a bar called The Pyramid Scheme. Over generously sized beers at Vivant, one of the town’s burgeoning microbreweries, I talked with a group of moderate conservatives and independents that Denniston had organized.

Located in the renovated chapel of a former funeral home, the place was loud, but Denniston wasn’t deterred, declaring over the din that, as an independent, he had signed the Voters Not Politicians petition outside this very brewery.

“Lansing is just as corrupt as Washington,” he said. “They’re passing the laws that they want to see and not what the people want to see.” He pointed to the Flint water crisis, for which he blamed Snyder. Denniston’s friend, Eric Baxter, who’s a big fan of Snyder, disagreed, citing Detroit’s comeback. Debate ensued about how exactly the lead came to contaminate Flint’s water.

Squeezed into one of the long communal tables in the buzzing brewpub, it occurred to me that something was taking place that I hadn’t experienced in a long time, not in Michigan, not at home in New York, not anywhere I’d recently been: a combative but friendly conversation between people clearly on different sides of the widening political divide. Politicians may not be able to communicate across the aisle, but the people still can. At least for now.

A representational democracy can only work if legislators have “an habitual recollection of their dependence on the people,” wrote James Madison, the likely author of Federalist No. 57. By making it nearly impossible to vote legislators out of office, partisan gerrymandering is “incompatible with democratic principles,” wrote Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan in the Gill v. Whitford concurring opinion. President Barack Obama warned against it. So did President Ronald Reagan.

“I think it’s wrong,” former House Speaker Newt Gingrich said in 2006. “I think it leads to bad government.” And yet, our highest court seems unable or unwilling to intervene. It may be up to us. The threat posed by gerrymandering is clear, and nothing less than representative democracy is at stake. Our only hope may be if we the people can reassert our right to representation in time, because politicians are well on their way to making themselves ballot-proof.